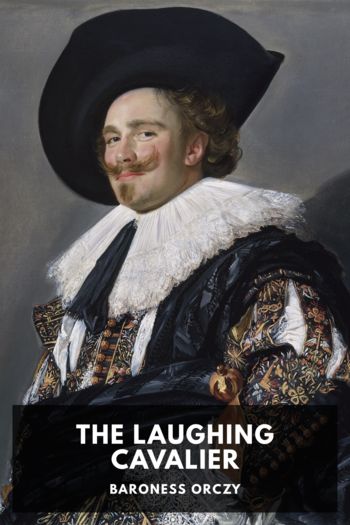

The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗

- Author: Baroness Orczy

Book online «The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗». Author Baroness Orczy

“It were wiser methinks,” quoth the enemy with a slight tone of mockery in his cheerful voice, “it were wiser to accept the help of my arms. They are strong, firm and not cramped. Try them, mejuffrouw, you will have no cause to regret it.”

Quite involuntarily—for of a truth she shrank from the mere touch of this rascal who obviously was in the pay of Stoutenburg, and doing the latter’s infamous work for him—quite involuntarily then, she placed her hand upon the arm which he had put out as a prop for her.

It was as firm as a rock. Leaning on it somewhat heavily she was able to struggle to her knees. This made her venturesome. She tried to stand up; but fatigue, the want of food, the excitement and anxiety which she had endured, combined with the fact that she had been in a recumbent position for many hours, caused her to turn desperately giddy. She swayed like a young sapling under the wind, and would have fallen but that the same strong arm firm as a rock was there to receive her ere she fell.

I suppose that dizziness deprived her of her full senses, else she would never have allowed that knave to lift her out of the sledge and then to carry her into a building, and up some narrow and very steep stairs. But this Diogenes did do, with but scant ceremony; he thought her protests foolish, and her attempts at lofty disdain pitiable. She was after all but a poor, helpless scrap of humanity, so slight and frail that as he carried her into the house, there was grave danger of his crushing her into nothingness as she lay in his arms.

Despite her pride and her aloofness he found it in his heart to pity her just now. Had she been fully conscious she would have hated to see herself pillowed thus against the doublet of so contemptible a knave; and here she was absolutely handed over body and soul to a nameless stranger, who in her sight, was probably no better than a menial—and this by the cynical act of one who next to her father was her most natural protector.

Yes, indeed he did pity her, for she seemed to him more than ever like that poor little songbird whom a lout had tortured for his own pleasure by plucking out its feathers one by one. It seemed monstrous that so delicate a creature should be the victim of men’s intrigues and passions. Why! even her breath had the subtle scent of tulips as it fanned his cheeks and nostrils when he stooped in order to look on her.

In the meanwhile he had been as good as his word. He had pushed on to Leyden in advance of the cortège, had roused the landlord of this hostelry and the serving wenches, and scattered money so freely that despite the lateness of the hour a large square room—the best in the house, and scrupulously clean as to the red-tiled floor and walnut furniture—was at once put at the disposal of the ladies of so noble a travelling company.

The maids were sent flying hither and thither, one into the kitchen to make ready some hot supper, the other to the linen press to find the finest set of bed linen all sweetly laid by in rosemary.

Diogenes, still carrying Gilda, pushed the heavy panelled door open with his foot, and without looking either to right or left of him made straight for the huge open hearth, wherein already logs of pinewood had been set ablaze, and beside which stood an armchair, covered with Utrecht velvet.

Into its inviting and capacious depths he deposited his inanimate burden, and only then did he become aware of two pairs of eyes, which were fixed upon him with very different expressions. A buxom wench in ample wide kirtle of striped duffle, had been busy when he entered in spreading clean linen sheets upon the narrow little bed built in the panelling of the room. From under her quaint winged cap of starched lace a pair of very round eyes, blue as the Ryn, peeped in naive undisguised admiration on the intruder, whilst from beneath her disordered coif Maria threw glances of deadly fury upon him.

Could looks but kill, Maria certes would have annihilated the low rascal who had dared to lay hands upon the noble jongejuffrouw. But our friend Diogenes was not a man to be perturbed either by admiring or condemning looks. He picked up a footstool from under the table and put it under the jongejuffrouw’s feet; then he looked about him for a pillow, and with scant ceremony took one straight out of the hands of the serving wench who was just shaking it up ready for the bed. His obvious intention was to place it behind the jongejuffrouw’s head, but at this act of unforgivable presumption Maria’s wrath cast aside all restraint. Like a veritable fury she strode up to the insolent rascal, and snatched the pillow from him, throwing on him such a look of angry contempt as should have sent him grovelling on his knees.

“Keep thy blood cool, mevrouw,” he said with the best of humour, “thy looks have already made a weak-kneed coward of me.”

With the dignity of an offended turkey hen, Maria arranged the pillow herself under her mistress’s head, having previously shaken it and carefully dusted off the blemish caused upon its surface by contact with an unclean hand. As for the footstool, she would not even allow it to remain there where that same unclean hand had placed it; she kicked it aside

Comments (0)