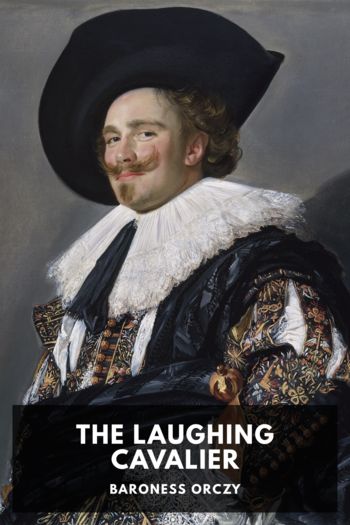

The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗

- Author: Baroness Orczy

Book online «The Laughing Cavalier, Baroness Orczy [the beginning after the end read novel TXT] 📗». Author Baroness Orczy

Diogenes made her a low bow, sweeping the floor with his plumed hat. The serving wench had much ado to keep a serious countenance, so comical did the mevrouw look in her wrath, and so mirth-provoking the gentleman with his graceful airs and unruffled temper. Anon laughter tickled her so that she had to run quickly out of the room, in order to indulge in a fit of uncontrolled mirth, away from the reproving glances of mevrouw.

It was the pleasant sound of that merry laughter outside the door that caused the jongejuffrouw to come to herself and to open wide, wondering eyes. She looked around her, vaguely puzzled, taking in the details of the cosy room, the crackling fire, the polished table, the inviting bed that exhaled an odour of dried rosemary.

Then her glance fell on Diogenes, who was standing hat in hand in the centre of the room, with the light from the blazing logs playing upon his smiling face, and the immaculate whiteness of his collar.

She frowned. And he who stood there—carelessly expectant—could not help wondering whether with that swift contemptuous glance which she threw on him, she had already recognized him.

“Mejuffrouw,” he said, thus checking with a loud word the angry exclamation which hovered on her lips, “if everything here is not entirely in accordance with your desires, I pray you but to command and it shall be remedied if human agency can but contrive to do so. As for me, I am entirely at your service—your majordomo, your servant, your outrider, anything you like to name me. Send but for your servant if you have need of aught; supper will be brought up to you immediately, and in the meanwhile I beg leave to free you from my unwelcome company.”

Already there was a goodly clatter of platters, and of crockery outside, and as the wench re-entered anon bearing a huge tray on which were set out several toothsome things, Diogenes contrived to make his exit without encountering further fusillades of angry glances.

He joined his friends in the taproom downstairs, and as he was young, vigorous and hungry he set to with them and ate a hearty supper. But he spoke very little and the rough jests of his brother philosophers met with but little response from him.

XVII An UnderstandingAt one hour after midnight the summons came.

Maria, majestic and unbending, sailed into the taproom where Pythagoras and Socrates were already stretched out full-length upon a couple of benches fast asleep and Diogenes still struggling to keep awake.

“The noble Jongejuffrouw Beresteyn desires your presence,” she said addressing the latter with lofty dignity.

At once he rose to his feet, and followed Maria up the stairs and into the lady’s room. From this room an inner door gave on another smaller alcove-like chamber, wherein a bed had been prepared for Maria.

Gilda somewhat curtly ordered her to retire.

“I will call you, Maria,” she said, “when I have need of you.”

Diogenes with elaborate courtesy threw the inner door open, and stood beside it plumed hat in hand while the mevrouw sailed past him, with arms folded across her ample bosom, and one of those dignified glances in her round eyes that should have annihilated this impious malapert, whose face—despite its airs of deference, was wreathed in an obviously ironical smile.

It was only when the heavy oaken door had fallen to behind her duenna that Gilda with an imperious little gesture called Diogenes before her.

He advanced hat in hand as was his wont, his magnificent figure very erect, his head with its wealth of untamed curls slightly bent. But he looked on her boldly with those laughter-filled, twinkling eyes of his and since he was young and neither ascetic nor yet a misanthrope, we may take it that he had some considerable pleasure in the contemplation of the dainty picture which she presented against the background of dull gold velvet: her small head propped against the cushions, and feathery curls escaping from under her coif and casting pearly, transparent shadows upon the ivory whiteness of her brow. Her two hands were resting each on an arm of the chair, and looked more delicate than ever now in the soft light of the tallow candles that burned feebly in the pewter candelabra upon the table.

Diogenes for the moment envied his friend Frans Hals for the power which the painter of pictures has of placing so dainty an image on record for all time. His look of bold admiration, however, caused Gilda’s glance to harden, and she drew herself up in her chair in an attitude more indicative of her rank and station and of her consciousness of his inferiority.

But not with a single look or smile did she betray whether she had recognized him or not.

“Your name?” she asked curtly.

His smile broadened—self-deprecatingly this time.

“They call me Diogenes,” he replied.

“A strange name,” she commented, “but ’tis of no consequence.”

“Of none whatever,” he rejoined, “I had not ventured to pronounce it, only that you deigned to ask.”

Again she frowned: the tone of gentle mockery had struck unpleasantly on her ear and she did not like that look of self-satisfied independence which sat on him as if to the manner born, when he was only an abject menial, paid to do dirty work for his betters.

“I have sent for you, sir,” she resumed after a slight pause, “because I wished to demand of you an explanation of your infamous conduct. Roguery and vagabondage are severely punished by our laws, and you have brought your neck uncommonly near the gallows by your act of highway robbery. Do you hear me?” she asked more peremptorily, seeing that he made no attempt at a reply.

“I hear you, mejuffrouw.”

“And what is your explanation?”

“That is my trouble, mejuffrouw. I have none to offer.”

“Do you refuse then to tell

Comments (0)