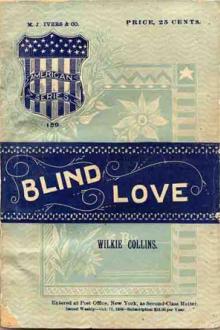

Blind Love, Wilkie Collins [ebook reader 8 inch TXT] 📗

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Book online «Blind Love, Wilkie Collins [ebook reader 8 inch TXT] 📗». Author Wilkie Collins

“But by another wickedness—and worse.”

“No—not another crime. Remember that this money is mine. It will come to my heirs some day, as surely as to-morrow’s sun will rise. Sooner or later it will be mine; I will make it sooner, that is all. The Insurance Company will lose nothing but the paltry interest for the remainder of my life. My dear, if it is disgraceful to do this I will endure disgrace. It is easier to bear that than constant self-reproach which I feel when I think of you and the losses I have inflicted upon you.”

Again he folded her in his arms; he knelt before her; he wept over her. Carried out of herself by this passion, Iris made no more resistance.

“Is it—is it,” she asked timidly, “too late to draw back?”

“It is too late,” he replied, thinking of the dead man below. “It is too late. All is completed.”

“My poor Harry! What shall we do? How shall we live? How shall we contrive never to be found out?”

She would not leave him, then. She accepted the situation. He was amazed at the readiness with which she fell; but he did not understand how she was ready to cling to him, for better for worse, through worse evils than this; nor could he understand how things formerly impossible to her had been rendered possible by the subtle deterioration of the moral nature, when a woman of lofty mind at the beginning loves and is united to a man of lower nature and coarser fibre than herself. Only a few months before, Iris would have swept aside these sophistrics with swift and resolute hand. Now she accepted them.

“You have fallen into the doctor’s hands, dear,” she said. “Pray Heaven it brings us not into worse evils! What can I say? it is through love of your wife—through love of your wife—oh! husband!” she threw herself into his arms, and forgave everything and accepted everything. Henceforth she would be—though this she knew not—the willing instrument of the two conspirators.

“I HAVE left this terrible thing about once too often already,” and Lord Harry took it from the table. “Let me put it in a place of safety.”

He unlocked a drawer and opened it. “I will put it here,” he said. “Why”—as if suddenly recollecting something—“here is my will. I shall be leaving that about on the table next. Iris, my dear, I have left everything to you. All will be yours.” He took out the document. “Keep it for me, Iris. It is yours. You may as well have it now, and then I know, in your careful hands, it will be quite safe. Not only is everything left to you, but you are the sole executrix.”

Iris took the will without a word. She understood, now, what it meant. If she was the sole executrix she would have to act. If everything was left to her she would have to receive the money. Thus, at a single step, she became not only cognisant of the conspiracy, but the chief agent and instrument to carry it out.

This done, her husband had only to tell her what had to be done at once, in consequence of her premature arrival. He had planned, he told her, not to send for her—not to let her know or suspect anything of the truth until the money had been paid to the widow by the Insurance Company. As things had turned out, it would be best for both of them to leave Passy at once—that very evening—before her arrival was known by anybody, and to let Vimpany carry out the rest of the business. He was quite to be trusted—he would do everything that was wanted. “Already,” he said, “the Office will have received from the doctor a notification of my death. Yesterday evening he wrote to everybody—to my brother—confound him!—and to the family solicitor. Every moment that I stay here increases the danger of my being seen and recognised—after the Office has been informed that I am dead.”

“Where are we to go?”

“I have thought of that. There is a little quiet town in Belgium where no English people ever come at all. We will go there, then we will take another name; we will be buried to the outer world, and will live, for the rest of our lives, for ourselves alone. Do you agree?”

“I will do, Harry, whatever you think best.”

“It will be for a time only. When all is ready, you will have to step to the front—the will in your hand to be proved—to receive what is due to you as the widow of Lord Harry Norland. You will go back to Belgium, after awhile, so as to disarm suspicion, to become once more the wife of William Linville.”

Iris sighed heavily, Then she caught her husband’s eyes gathering with doubt, and she smiled again.

“In everything, Harry,” she said, “I am your servant. When shall we start?”

“Immediately. I have only to write a letter to the doctor. Where is your bag? Is this all? Let me go first to see that no one is about. Have you got the will? Oh! it is here—yes—in the bag. I will bring along the bag.”

He ran downstairs, and came up quickly.

“The nurse has returned,” he said. “She is in the spare room.”

“What nurse?”

“The nurse who came after Fanny left. The man was better, but the doctor thought it wisest to have a nurse to the end,” he explained hurriedly, and she suspected nothing till afterwards. “Come down quietly—go out by the back-door—she will not see you.” So Iris obeyed. She went out of her own house like a thief, or like her own maid Fanny, had she known. She passed through the garden, and out of the garden into the road. There she waited for her husband.

Lord Harry sat down and wrote a letter.

“Dear Doctor,” he said, “while you are arranging things outside an unexpected event has happened inside. Nothing happens but the unexpected. My wife has come back. It is the most unexpected event of any. Anything else might have happened. Most fortunately she has not seen the spare bedroom, and has no idea of its contents.

“At this point reassure yourself.

“My wife has gone.

“She found on the table your first print of the negative. The sight of this before she saw me threw her into some kind of swoon, from which, however, she recovered.

“I have explained things to a certain point. She understands that Lord Harry Norland is deceased. She does not understand that it was necessary to have a funeral; there is no necessity to tell her of that. I think she understands that she must not seem to have been here. Therefore she goes away immediately.

“The nurse has not seen her. No one has seen her.

“She understands, further, that as the widow, heir, and executrix of Lord Harry she will have to prove his will, and to receive the money due to him by the Insurance Company. She will do this out of love for her husband. I think that the persuasive powers of a certain person have never yet been estimated at their true value.

“Considering the vital importance of getting her out of the place before she can learn anything of the spare bedroom, and of getting me out of the place before any messenger can arrive from the London office, I think you will agree with me that I am right in leaving Passy—and Paris—with Lady Harry this very afternoon.

“You may write to William Linville, Poste-Restante, Louvain, Belgium. I am sure I can trust you to destroy this letter.

“Louvain is a quiet, out-of-the-way place, where one can live quite separated from all old friends, and very cheaply.

“Considering the small amount of money that I have left, I rely upon you to exercise the greatest economy. I do not know how long it may be before just claims are paid up—perhaps in two months—perhaps in six—but until things are settled there will be tightness.

“At the same time it will not be difficult, as soon as Lady Harry goes to London, to obtain some kind of advance from the family solicitor on the strength of the insurance due to her from her late husband.

“I am sorry, dear doctor, to leave you alone over the obsequies of this unfortunate gentleman. You will also have, I hear, a good deal of correspondence with his family. You may, possibly, have to see them in England. All this you will do, and do very well. Your bill for medical attendance you will do well to send in to the widow.

“One word more. Fanny Mere, the maid, has gone to London; but she has not seen Lady Harry. As soon as she hears that her mistress has left London she will be back to Passy. She may come at any moment. I think if I were you I would meet her at the garden gate and send her on. It would be inconvenient if she were to arrive before the funeral.

“My dear doctor, I rely on your sense, your prudence, and your capability.—Yours very sincerely,

“Your ENGLISH FRIEND.”

He read this letter very carefully. Nothing in it he thought the least dangerous, and yet something suggested danger. However, he left it; he was obliged to caution and warn the doctor, and he was obliged to get his wife away as quietly as possible.

This done, he packed up his things and hurried off to the station, and Passy saw him no more.

The next day the mortal remains of Lord Harry Norland were lowered into the grave.

IT was about five o’clock on Saturday afternoon. The funeral was over. The unfortunate young Irish gentleman was now lying in the cemetery of Auteuil in a grave purchased in perpetuity. His name, age, and rank were duly inscribed in the registers, and the cause of his death was vouched for by the English physician who had attended him at the request of his family. He was accompanied, in going through the formalities, by the respectable woman who had nursed the sick man during his last seizure. Everything was perfectly in order. The physician was the only mourner at the funeral. No one was curious about the little procession. A funeral, more or less, excites no attention.

The funeral completed, the doctor gave orders for a single monument to be put in memory of Lord Harry Norland, thus prematurely cut off. He then returned to the cottage, paid and dismissed the nurse, taking her address in case he should find an opportunity, as he hoped, to recommend her among his numerous and distinguished clientele, and proceeded to occupy himself in setting everything in order before giving over the key to the landlord. First of all he removed the medicine bottles from the cupboard with great care, leaving nothing. Most of the bottles he threw outside into the dust-hole; one or two he placed in a fire which he made for the purpose in the kitchen: they were shortly reduced to two or three lumps of molten glass. These contained, no doubt, the mysteries and secrets of Science. Then he went into every room and searched in every possible place for any letters or papers which might have been left about. Letters left about are always indiscreet, and the

Comments (0)