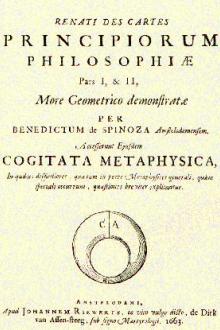

The Philosophy of Spinoza, Benedictus de Spinoza [read full novel .txt] 📗

- Author: Benedictus de Spinoza

- Performer: -

Book online «The Philosophy of Spinoza, Benedictus de Spinoza [read full novel .txt] 📗». Author Benedictus de Spinoza

If we now examine the revelations to Moses, we shall find that they were accommodated to these opinions; as he believed that the Divine Nature was subject to the conditions of mercy, graciousness, etc., so God was revealed to him in accordance with his idea and under these attributes (see Exodus xxxiv. 6, 7, and the second commandment). Further it is related (Ex. xxxiii. 18) that Moses asked of God that he might behold Him, but as Moses (as we have said) had formed no mental image of God, and God (as I have shown) only revealed Himself to the prophets in accordance with the disposition of their imagination, He did not reveal Himself in any form. This, I repeat, was because the imagination of Moses was unsuitable, for other prophets bear witness that they saw the Lord; for instance, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, etc. For this reason God answered Moses, "Thou canst not see My face;" and inasmuch as Moses believed that God can be looked upon—that is, that no contradiction of the Divine nature is therein involved (for otherwise he would never have preferred his request)—it is added, "For no one shall look on Me and live," thus giving a reason in accordance with Moses' idea, for it is not stated that a contradiction of the Divine nature would be involved, as was really the case, but that the thing would not come to pass because of human infirmity....

Lastly, as Moses believed that God dwelt in the heavens, God was revealed to him as coming down from heaven on to a mountain, and in order to talk with the Lord Moses went up the mountain, which he certainly need not have done if he could have conceived of God as omnipresent.

The Israelites knew scarcely anything of God, although He was revealed to them; and this is abundantly evident from their transferring, a few days afterwards, the honor and worship due to Him to a calf, which they believed to be the god who had brought them out of Egypt. In truth, it is hardly likely that men accustomed to the superstitions of Egypt, uncultivated and sunk in most abject slavery, should have held any sound notions about the Deity, or that Moses should have taught them anything beyond a rule of right living; inculcating it not like a philosopher, as the result of freedom, but like a lawgiver compelling them to be moral by legal authority. Thus the rule of right living, the worship and love of God, was to them rather a bondage than the true liberty, the gift and grace of the Deity. Moses bid them love God and keep His law, because they had in the past received benefits from Him (such as the deliverance from slavery in Egypt), and further terrified them with threats if they transgressed His commands, holding out many promises of good if they should observe them; thus treating them as parents treat irrational children. It is, therefore, certain that they knew not the excellence of virtue and the true happiness.

Jonah thought that he was fleeing from the sight of God, which seems to show that he too held that God had entrusted the care of the nations outside Judæa to other substituted powers. No one in the whole of the Old Testament speaks more rationally of God than Solomon, who in fact surpassed all the men of his time in natural ability. Yet he considered himself above the law (esteeming it only to have been given for men without reasonable and intellectual grounds for their actions), and made small account of the laws concerning kings, which are mainly three: nay, he openly violated them (in this he did wrong, and acted in a manner unworthy of a philosopher, by indulging in sensual pleasure), and taught that all Fortune's favors to mankind are vanity, that humanity has no nobler gift than wisdom, and no greater punishment than folly. (See Proverbs xvi. 22, 23.)

... God adapted revelations to the understanding and opinions of the prophets, and ... in matters of theory without bearing on charity or morality, the prophets could be, and, in fact, were ignorant, and held conflicting opinions. It therefore follows that we must by no means go to the prophets for knowledge, either of natural or of spiritual phenomena.

We have determined, then, that we are only bound to believe in the prophetic writings, the object and substance of the revelation; with regard to the details, every one may believe or not, as he likes.

For instance, the revelation to Cain only teaches us that God admonished him to lead the true life, for such alone is the object and substance of the revelation, not doctrines concerning free will and philosophy. Hence, though the freedom of the will is clearly implied in the words of the admonition, we are at liberty to hold a contrary opinion, since the words and reasons were adapted to the understanding of Cain.

So, too, the revelation to Micaiah would only teach that God revealed to him the true issue of the battle between Ahab and Aram; and this is all we are bound to believe. Whatever else is contained in the revelation concerning the true and the false Spirit of God, the army of heaven standing on the right hand and on the left, and all the other details, does not affect us at all. Every one may believe as much of it as his reason allows.

The reasonings by which the Lord displayed His power to Job (if they really were a revelation, and the author of the history is narrating, and not merely, as some suppose, rhetorically adorning his own conceptions), would come under the same category—that is, they were adapted to Job's understanding, for the purpose of convincing him, and are not universal, or for the convincing of all men.

We can come to no different conclusion with respect to the reasonings of Christ, by which He convicted the Pharisees of pride and ignorance, and exhorted His disciples to lead the true life. He adapted them to each man's opinions and principles. For instance, when He said to the Pharisees (Matt. xii. 26), "And if Satan cast out devils, his house is divided against itself, how then shall his kingdom stand?" He only wished to convince the Pharisees according to their own principles, not to teach that there are devils, or any kingdom of devils. So, too, when He said to His disciples (Matt. viii. 10), "See that ye despise not one of these little ones, for I say unto you that their angels," etc., He merely desired to warn them against pride and despising any of their fellows, not to insist on the actual reason given, which was simply adopted in order to persuade them more easily.

Lastly, we should say exactly the same of the apostolic signs and reasonings, but there is no need to go further into the subject. If I were to enumerate all the passages of Scripture addressed only to individuals, or to a particular man's understanding, and which cannot, without great danger to philosophy, be defended as Divine doctrines, I should go far beyond the brevity at which I aim. Let it suffice then, to have indicated a few instances of general application, and let the curious reader consider others by himself. Although the points we have just raised concerning prophets and prophecy are the only ones which have any direct bearing on the end in view, namely, the separation of Philosophy from Theology, still, as I have touched on the general question, I may here inquire whether the gift of prophecy was peculiar to the Hebrews, or whether it was common to all nations. I must then come to a conclusion about the vocation of the Hebrews, all of which I shall do in the ensuing chapter.

[4] From the Tr. Th.-P. ch. i Of Prophecy; and ch. ii of Of Prophets.

[5] ... I will tell you that I do not think it necessary for salvation to know Christ according to the flesh; but with regard to the Eternal Son of God, that is the Eternal Wisdom of God, which has manifested itself in all things and especially in the human mind, and above all in Christ Jesus, the case is far otherwise. For without this no one can come to a state of blessedness, inasmuch as it alone teaches what is true or false, good or evil. And, inasmuch as this wisdom was made especially manifest through Jesus Christ, as I have said, His disciples preached it, in so far as it was revealed to them through Him, and thus showed that they could rejoice in that spirit of Christ more than the rest of mankind. The doctrines added by certain churches, such as that God took upon Himself

Comments (0)