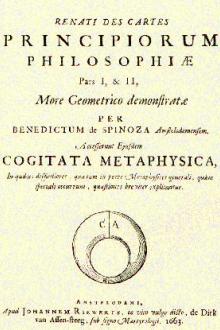

The Philosophy of Spinoza, Benedictus de Spinoza [read full novel .txt] 📗

- Author: Benedictus de Spinoza

- Performer: -

Book online «The Philosophy of Spinoza, Benedictus de Spinoza [read full novel .txt] 📗». Author Benedictus de Spinoza

The more perfect a thing is, the more reality it possesses, and consequently the more it acts and the less it suffers. Inversely also it may be demonstrated in the same way that the more a thing acts the more perfect it is. Hence it follows that that part of the mind which abides, whether great or small, is more perfect than the other part. For the part of the mind which is eternal is the intellect, through which alone we are said to act, but that part which, as we have shown, perishes, is the imagination itself, through which alone we are said to suffer. Therefore that part which abides, whether great or small, is more perfect than the latter.

These are the things I proposed to prove concerning the mind, in so far as it is considered without relation to the existence of the body, and from these, and other propositions, it is evident that our mind, in so far as it understands, is an eternal mode of thought, which is determined by another eternal mode of thought, and this again by another, and so on ad infinitum, so that all taken together form the eternal and infinite intellect of God.

ConclusionThe primary and sole foundation of virtue or of the proper conduct of life is to seek our own profit. But in order to determine what reason prescribes as profitable, we had no regard to the eternity of the mind. Therefore, although we were at that time ignorant that the mind is eternal, we considered as of primary importance those things which we have shown are related to strength of mind and generosity; and therefore, even if we were now ignorant of the eternity of the mind, we should consider those commands of reason as of primary importance.

The creed of the multitude seems to be different from this; for most persons seem to believe that they are free in so far as it is allowed them to obey their lusts, and that they give up a portion of their rights, in so far as they are bound to live according to the commands of divine law. Piety, therefore, and religion,[42] and absolutely all those things that are related to greatness of soul, they believe to be burdens which they hope to be able to lay aside after death; hoping also to receive some reward for their bondage, that is to say, for their piety and religion. It is not merely this hope, however, but also and chiefly fear of dreadful punishments after death, by which they are induced to live according to the commands of divine law, that is to say, as far as their feebleness and impotent mind will permit; and if this hope and fear were not present to them, but if they, on the contrary, believed that minds perish with the body, and that there is no prolongation of life for miserable creatures exhausted with the burden of their piety, they would return to ways of their own liking. They would prefer to let everything be controlled by their own passions, and to obey fortune rather than themselves.

This seems to me as absurd as if a man, because he does not believe that he will be able to feed his body with good food to all eternity, should desire to satiate himself with poisonous and deadly drugs; or as if, because he sees that the mind is not eternal or immortal, he should therefore prefer to be mad and to live without reason—absurdities so great that they scarcely deserve to be repeated.

Blessedness consists in love towards God, which arises from the third kind of knowledge, and this love, therefore, must be related to the mind in so far as it acts. Blessedness, therefore, is virtue itself. Again, the more the mind delights in this divine love or blessedness, the more it understands, that is to say, the greater is the power it has over its emotions and the less it suffers from emotions which are evil. Therefore, it is because the mind delights in this divine love or blessedness that it possesses the power of restraining the lusts; and because the power of man to restrain the emotions is in the intellect alone, no one, therefore, delights in blessedness because he has restrained his emotions, but, on the contrary, the power of restraining his lusts springs from blessedness itself.

I have finished everything I wished to explain concerning the power of the mind over the emotions and concerning its liberty. From what has been said we see what is the strength of the wise man, and how much he surpasses the ignorant who is driven forward by lust alone. For the ignorant man is not only agitated by external causes in many ways, and never enjoys true peace of soul, but lives also ignorant, as it were, both of God and of things, and as soon as he ceases to suffer ceases also to be. On the other hand, the wise man, in so far as he is considered as such, is scarcely ever moved in his mind, but, being conscious by a certain eternal necessity of himself, of God, and of things, never ceases to be, and always enjoys true peace of soul.

If the way which, as I have shown, leads hither seem very difficult, it can nevertheless be found. It must indeed be difficult since it is so seldom discovered; for if salvation lay ready to hand and could be discovered without great labor, how could it be possible that it should be neglected almost by everybody? But all noble things are as difficult as they are rare.

[42] Everything which we desire and do, of which we are the cause in so far as we possess an idea of God, or in so far as we know God, I refer to Religion. The desire of doing well which is born in us, because we live according to the guidance of reason, I call Piety.

APPENDIXSpinoza's Ethics, demonstrated in geometrical order, consists of five parts; from these parts the following selections have been taken:

the end

Page vii: "affectiones" sic

Page xxvi: "villified" amended to "vilified"

Page xxvii: "chose" amended to "choose" (twice); "forego" sic

Page xxxvi: "antedeluvian" amended to "antediluvian"

Page lix: "goverance" amended to "governance"

Page 1: "oursleves" amended to "ourselves"

Page 6: "superstitition" amended to "superstition"

Page 9: "conprehension" amended to "comprehension"

Page 26: "chose" amended to "choose"

Page 28: "interpretating" amended to "interpreting"

Page 45: "phophet" amended to "prophet"

Page 51: "came" amended to "come"

Page 69: "patriachs" amended to "patriarchs"

Page 84: "refer" amended to "prefer"

Page 135: "appetities" amended to "appetites"

Page 204: "thy" amended to "they" and "thir" amended to "their"

Page 229: "Explanations" amended to "Explanation"

Page 276: "others" amended to "other"

Page 284: "mutitude" amended to "multitude"

Page 362: "propositon" amended to "proposition"

Abbreviations in footnotes and references have been standardized.

Accents and hyphenation have generally been standardised.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Philosophy of Spinoza, by Baruch de Spinoza

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PHILOSOPHY OF SPINOZA ***

***** This file should be named 31205-h.htm or 31205-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/1/2/0/31205/

Produced by Alicia Williams and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Comments (0)