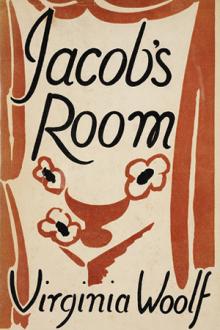

Jacob's Room, Virginia Woolf [non fiction books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Virginia Woolf

- Performer: 0140185704

Book online «Jacob's Room, Virginia Woolf [non fiction books to read .txt] 📗». Author Virginia Woolf

correctly his page of the eternal lesson-book, would have moved a woman.

Jacob, of course, was not a woman. The sight of Timmy Durrant was no

sight for him, nothing to set against the sky and worship; far from it.

They had quarrelled. Why the right way to open a tin of beef, with

Shakespeare on board, under conditions of such splendour, should have

turned them to sulky schoolboys, none can tell. Tinned beef is cold

eating, though; and salt water spoils biscuits; and the waves tumble and

lollop much the same hour after hour—tumble and lollop all across the

horizon. Now a spray of seaweed floats past-now a log of wood. Ships

have been wrecked here. One or two go past, keeping their own side of

the road. Timmy knew where they were bound, what their cargoes were,

and, by looking through his glass, could tell the name of the line, and

even guess what dividends it paid its shareholders. Yet that was no

reason for Jacob to turn sulky.

The Scilly Isles had the look of mountain-tops almost a-wash….

Unfortunately, Jacob broke the pin of the Primus stove.

The Scilly Isles might well be obliterated by a roller sweeping straight

across.

But one must give young men the credit of admitting that, though

breakfast eaten under these circumstances is grim, it is sincere enough.

No need to make conversation. They got out their pipes.

Timmy wrote up some scientific observations; and—what was the question

that broke the silence—the exact time or the day of the month? anyhow,

it was spoken without the least awkwardness; in the most matter-of-fact

way in the world; and then Jacob began to unbutton his clothes and sat

naked, save for his shirt, intending, apparently, to bathe.

The Scilly Isles were turning bluish; and suddenly blue, purple, and

green flushed the sea; left it grey; struck a stripe which vanished; but

when Jacob had got his shirt over his head the whole floor of the waves

was blue and white, rippling and crisp, though now and again a broad

purple mark appeared, like a bruise; or there floated an entire emerald

tinged with yellow. He plunged. He gulped in water, spat it out, struck

with his right arm, struck with his left, was towed by a rope, gasped,

splashed, and was hauled on board.

The seat in the boat was positively hot, and the sun warmed his back as

he sat naked with a towel in his hand, looking at the Scilly Isles

which—confound it! the sail flapped. Shakespeare was knocked overboard.

There you could see him floating merrily away, with all his pages

ruffling innumerably; and then he went under.

Strangely enough, you could smell violets, or if violets were impossible

in July, they must grow something very pungent on the mainland then. The

mainland, not so very far off—you could see clefts in the cliffs, white

cottages, smoke going up—wore an extraordinary look of calm, of sunny

peace, as if wisdom and piety had descended upon the dwellers there. Now

a cry sounded, as of a man calling pilchards in a main street. It wore

an extraordinary look of piety and peace, as if old men smoked by the

door, and girls stood, hands on hips, at the well, and horses stood; as

if the end of the world had come, and cabbage fields and stone walls,

and coast-guard stations, and, above all, the white sand bays with the

waves breaking unseen by any one, rose to heaven in a kind of ecstasy.

But imperceptibly the cottage smoke droops, has the look of a mourning

emblem, a flag floating its caress over a grave. The gulls, making their

broad flight and then riding at peace, seem to mark the grave.

No doubt if this were Italy, Greece, or even the shores of Spain,

sadness would be routed by strangeness and excitement and the nudge of a

classical education. But the Cornish hills have stark chimneys standing

on them; and, somehow or other, loveliness is infernally sad. Yes, the

chimneys and the coast-guard stations and the little bays with the waves

breaking unseen by any one make one remember the overpowering sorrow.

And what can this sorrow be?

It is brewed by the earth itself. It comes from the houses on the coast.

We start transparent, and then the cloud thickens. All history backs our

pane of glass. To escape is vain.

But whether this is the right interpretation of Jacob’s gloom as he sat

naked, in the sun, looking at the Land’s End, it is impossible to say;

for he never spoke a word. Timmy sometimes wondered (only for a second)

whether his people bothered him…. No matter. There are things that

can’t be said. Let’s shake it off. Let’s dry ourselves, and take up the

first thing that comes handy…. Timmy Durrant’s notebook of scientific

observations.

“Now…” said Jacob.

It is a tremendous argument.

Some people can follow every step of the way, and even take a little

one, six inches long, by themselves at the end; others remain observant

of the external signs.

The eyes fix themselves upon the poker; the right hand takes the poker

and lifts it; turns it slowly round, and then, very accurately, replaces

it. The left hand, which lies on the knee, plays some stately but

intermittent piece of march music. A deep breath is taken; but allowed

to evaporate unused. The cat marches across the hearthrug. No one

observes her.

“That’s about as near as I can get to it,” Durrant wound up.

The next minute is quiet as the grave.

“It follows…” said Jacob.

Only half a sentence followed; but these half-sentences are like flags

set on tops of buildings to the observer of external sights down below.

What was the coast of Cornwall, with its violet scents, and mourning

emblems, and tranquil piety, but a screen happening to hang straight

behind as his mind marched up?

“It follows…” said Jacob.

“Yes,” said Timmy, after reflection. “That is so.”

Now Jacob began plunging about, half to stretch himself, half in a kind

of jollity, no doubt, for the strangest sound issued from his lips as he

furled the sail, rubbed the plates—gruff, tuneless—a sort of pasan,

for having grasped the argument, for being master of the situation,

sunburnt, unshaven, capable into the bargain of sailing round the world

in a ten-ton yacht, which, very likely, he would do one of these days

instead of settling down in a lawyer’s office, and wearing spats.

“Our friend Masham,” said Timmy Durrant, “would rather not be seen in

our company as we are now.” His buttons had come off.

“D’you know Masham’s aunt?” said Jacob.

“Never knew he had one,” said Timmy.

“Masham has millions of aunts,” said Jacob.

“Masham is mentioned in Domesday Book,” said Timmy.

“So are his aunts,” said Jacob.

“His sister,” said Timmy, “is a very pretty girl.”

“That’s what’ll happen to you, Timmy,” said Jacob.

“It’ll happen to you first,” said Timmy.

“But this woman I was telling you about—Masham’s aunt—”

“Oh, do get on,” said Timmy, for Jacob was laughing so much that he

could not speak.

“Masham’s aunt…”

Timmy laughed so much that he could not speak.

“Masham’s aunt…”

“What is there about Masham that makes one laugh?” said Timmy.

“Hang it all—a man who swallows his tie-pin,” said Jacob.

“Lord Chancellor before he’s fifty,” said Timmy.

“He’s a gentleman,” said Jacob.

“The Duke of Wellington was a gentleman,” said Timmy.

“Keats wasn’t.”

“Lord Salisbury was.”

“And what about God?” said Jacob.

The Scilly Isles now appeared as if directly pointed at by a golden

finger issuing from a cloud; and everybody knows how portentous that

sight is, and how these broad rays, whether they light upon the Scilly

Isles or upon the tombs of crusaders in cathedrals, always shake the

very foundations of scepticism and lead to jokes about God.

“Abide with me:

Fast falls the eventide;

The shadows deepen;

Lord, with me abide,”

sang Timmy Durrant.

“At my place we used to have a hymn which began

Great God, what do I see and hear?”

said Jacob.

Gulls rode gently swaying in little companies of two or three quite near

the boat; the cormorant, as if following his long strained neck in

eternal pursuit, skimmed an inch above the water to the next rock; and

the drone of the tide in the caves came across the water, low,

monotonous, like the voice of some one talking to himself.

“Rock of Ages, cleft for me,

Let me hide myself in thee,”

sang Jacob.

Like the blunt tooth of some monster, a rock broke the surface; brown;

overflown with perpetual waterfalls.

“Rock of Ages,”

Jacob sang, lying on his back, looking up into the sky at midday, from

which every shred of cloud had been withdrawn, so that it was like

something permanently displayed with the cover off.

By six o’clock a breeze blew in off an icefield; and by seven the water

was more purple than blue; and by half-past seven there was a patch of

rough gold-beater’s skin round the Scilly Isles, and Durrant’s face, as

he sat steering, was of the colour of a red lacquer box polished for

generations. By nine all the fire and confusion had gone out of the sky,

leaving wedges of apple-green and plates of pale yellow; and by ten the

lanterns on the boat were making twisted colours upon the waves,

elongated or squat, as the waves stretched or humped themselves. The

beam from the lighthouse strode rapidly across the water. Infinite

millions of miles away powdered stars twinkled; but the waves slapped

the boat, and crashed, with regular and appalling solemnity, against the

rocks.

Although it would be possible to knock at the cottage door and ask for a

glass of milk, it is only thirst that would compel the intrusion. Yet

perhaps Mrs. Pascoe would welcome it. The summer’s day may be wearing

heavy. Washing in her little scullery, she may hear the cheap clock on

the mantelpiece tick, tick, tick … tick, tick, tick. She is alone in

the house. Her husband is out helping Farmer Hosken; her daughter

married and gone to America. Her elder son is married too, but she does

not agree with his wife. The Wesleyan minister came along and took the

younger boy. She is alone in the house. A steamer, probably bound for

Cardiff, now crosses the horizon, while near at hand one bell of a

foxglove swings to and fro with a bumble-bee for clapper. These white

Cornish cottages are built on the edge of the cliff; the garden grows

gorse more readily than cabbages; and for hedge, some primeval man has

piled granite boulders. In one of these, to hold, an historian

conjectures, the victim’s blood, a basin has been hollowed, but in our

time it serves more tamely to seat those tourists who wish for an

uninterrupted view of the Gurnard’s Head. Not that any one objects to a

blue print dress and a white apron in a cottage garden.

“Look—she has to draw her water from a well in the garden.”

“Very lonely it must be in winter, with the wind sweeping over those

hills, and the waves dashing on the rocks.”

Even on a summer’s day you hear them murmuring.

Having drawn her water, Mrs. Pascoe went in. The tourists regretted that

they had brought no glasses, so that they might have read the name of

the tramp steamer. Indeed, it was such a fine day that there was no

Comments (0)