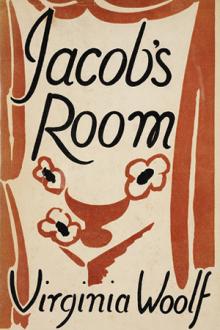

Jacob's Room, Virginia Woolf [non fiction books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Virginia Woolf

- Performer: 0140185704

Book online «Jacob's Room, Virginia Woolf [non fiction books to read .txt] 📗». Author Virginia Woolf

Two fishing luggers, presumably from St. Ives Bay, were now sailing in

an opposite direction from the steamer, and the floor of the sea became

alternately clear and opaque. As for the bee, having sucked its fill of

honey, it visited the teasle and thence made a straight line to Mrs.

Pascoe’s patch, once more directing the tourists’ gaze to the old

woman’s print dress and white apron, for she had come to the door of the

cottage and was standing there.

There she stood, shading her eyes and looking out to sea.

For the millionth time, perhaps, she looked at the sea. A peacock

butterfly now spread himself upon the teasle, fresh and newly emerged,

as the blue and chocolate down on his wings testified. Mrs. Pascoe went

indoors, fetched a cream pan, came out, and stood scouring it. Her face

was assuredly not soft, sensual, or lecherous, but hard, wise, wholesome

rather, signifying in a room full of sophisticated people the flesh and

blood of life. She would tell a lie, though, as soon as the truth.

Behind her on the wall hung a large dried skate. Shut up in the parlour

she prized mats, china mugs, and photographs, though the mouldy little

room was saved from the salt breeze only by the depth of a brick, and

between lace curtains you saw the gannet drop like a stone, and on

stormy days the gulls came shuddering through the air, and the steamers’

lights were now high, now deep. Melancholy were the sounds on a winter’s

night.

The picture papers were delivered punctually on Sunday, and she pored

long over Lady Cynthia’s wedding at the Abbey. She, too, would have

liked to ride in a carriage with springs. The soft, swift syllables of

educated speech often shamed her few rude ones. And then all night to

hear the grinding of the Atlantic upon the rocks instead of hansom cabs

and footmen whistling for motor cars. … So she may have dreamed,

scouring her cream pan. But the talkative, nimble-witted people have

taken themselves to towns. Like a miser, she has hoarded her feelings

within her own breast. Not a penny piece has she changed all these

years, and, watching her enviously, it seems as if all within must be

pure gold.

The wise old woman, having fixed her eyes upon the sea, once more

withdrew. The tourists decided that it was time to move on to the

Gurnard’s Head.

Three seconds later Mrs. Durrant rapped upon the door.

“Mrs. Pascoe?” she said.

Rather haughtily, she watched the tourists cross the field path. She

came of a Highland race, famous for its chieftains.

Mrs. Pascoe appeared.

“I envy you that bush, Mrs. Pascoe,” said Mrs. Durrant, pointing the

parasol with which she had rapped on the door at the fine clump of St.

John’s wort that grew beside it. Mrs. Pascoe looked at the bush

deprecatingly.

“I expect my son in a day or two,” said Mrs. Durrant. “Sailing from

Falmouth with a friend in a little boat. … Any news of Lizzie yet,

Mrs. Pascoe?”

Her long-tailed ponies stood twitching their ears on the road twenty

yards away. The boy, Curnow, flicked flies off them occasionally. He saw

his mistress go into the cottage; come out again; and pass, talking

energetically to judge by the movements of her hands, round the

vegetable plot in front of the cottage. Mrs. Pascoe was his aunt. Both

women surveyed a bush. Mrs. Durrant stooped and picked a sprig from it.

Next she pointed (her movements were peremptory; she held herself very

upright) at the potatoes. They had the blight. All potatoes that year

had the blight. Mrs. Durrant showed Mrs. Pascoe how bad the blight was

on her potatoes. Mrs. Durrant talked energetically; Mrs. Pascoe listened

submissively. The boy Curnow knew that Mrs. Durrant was saying that it

is perfectly simple; you mix the powder in a gallon of water; “I have

done it with my own hands in my own garden,” Mrs. Durrant was saying.

“You won’t have a potato left—you won’t have a potato left,” Mrs.

Durrant was saying in her emphatic voice as they reached the gate. The

boy Curnow became as immobile as stone.

Mrs. Durrant took the reins in her hands and settled herself on the

driver’s seat.

“Take care of that leg, or I shall send the doctor to you,” she called

back over her shoulder; touched the ponies; and the carriage started

forward. The boy Curnow had only just time to swing himself up by the

toe of his boot. The boy Curnow, sitting in the middle of the back seat,

looked at his aunt.

Mrs. Pascoe stood at the gate looking after them; stood at the gate till

the trap was round the corner; stood at the gate, looking now to the

right, now to the left; then went back to her cottage.

Soon the ponies attacked the swelling moor road with striving forelegs.

Mrs. Durrant let the reins fall slackly, and leant backwards. Her

vivacity had left her. Her hawk nose was thin as a bleached bone through

which you almost see the light. Her hands, lying on the reins in her

lap, were firm even in repose. The upper lip was cut so short that it

raised itself almost in a sneer from the front teeth. Her mind skimmed

leagues where Mrs. Pascoe’s mind adhered to its solitary patch. Her mind

skimmed leagues as the ponies climbed the hill road. Forwards and

backwards she cast her mind, as if the roofless cottages, mounds of

slag, and cottage gardens overgrown with foxglove and bramble cast shade

upon her mind. Arrived at the summit, she stopped the carriage. The pale

hills were round her, each scattered with ancient stones; beneath was

the sea, variable as a southern sea; she herself sat there looking from

hill to sea, upright, aquiline, equally poised between gloom and

laughter. Suddenly she flicked the ponies so that the boy Curnow had to

swing himself up by the toe of his boot.

The rooks settled; the rooks rose. The trees which they touched so

capriciously seemed insufficient to lodge their numbers. The tree-tops

sang with the breeze in them; the branches creaked audibly and dropped

now and then, though the season was midsummer, husks or twigs. Up went

the rooks and down again, rising in lesser numbers each time as the

sager birds made ready to settle, for the evening was already spent

enough to make the air inside the wood almost dark. The moss was soft;

the tree-trunks spectral. Beyond them lay a silvery meadow. The pampas

grass raised its feathery spears from mounds of green at the end of the

meadow. A breadth of water gleamed. Already the convolvulus moth was

spinning over the flowers. Orange and purple, nasturtium and cherry pie,

were washed into the twilight, but the tobacco plant and the passion

flower, over which the great moth spun, were white as china. The rooks

creaked their wings together on the tree-tops, and were settling down

for sleep when, far off, a familiar sound shook and trembled—increased

—fairly dinned in their ears—scared sleepy wings into the air again—

the dinner bell at the house.

After six days of salt wind, rain, and sun, Jacob Flanders had put on a

dinner jacket. The discreet black object had made its appearance now and

then in the boat among tins, pickles, preserved meats, and as the voyage

went on had become more and more irrelevant, hardly to be believed in.

And now, the world being stable, lit by candle-light, the dinner jacket

alone preserved him. He could not be sufficiently thankful. Even so his

neck, wrists, and face were exposed without cover, and his whole person,

whether exposed or not, tingled and glowed so as to make even black

cloth an imperfect screen. He drew back the great red hand that lay on

the tablecloth. Surreptitiously it closed upon slim glasses and curved

silver forks. The bones of the cutlets were decorated with pink frills-and yesterday he had gnawn ham from the bone! Opposite him were hazy,

semi-transparent shapes of yellow and blue. Behind them, again, was the

grey-green garden, and among the pear-shaped leaves of the escallonia

fishing-boats seemed caught and suspended. A sailing ship slowly drew

past the women’s backs. Two or three figures crossed the terrace hastily

in the dusk. The door opened and shut. Nothing settled or stayed

unbroken. Like oars rowing now this side, now that, were the sentences

that came now here, now there, from either side of the table.

“Oh, Clara, Clara!” exclaimed Mrs. Durrant, and Timothy Durrant adding,

“Clara, Clara,” Jacob named the shape in yellow gauze Timothy’s sister,

Clara. The girl sat smiling and flushed. With her brother’s dark eyes,

she was vaguer and softer than he was. When the laugh died down she

said: “But, mother, it was true. He said so, didn’t he? Miss Eliot

agreed with us. …”

But Miss Eliot, tall, grey-headed, was making room beside her for the

old man who had come in from the terrace. The dinner would never end,

Jacob thought, and he did not wish it to end, though the ship had sailed

from one corner of the window-frame to the other, and a light marked the

end of the pier. He saw Mrs. Durrant gaze at the light. She turned to

him.

“Did you take command, or Timothy?” she said. “Forgive me if I call you

Jacob. I’ve heard so much of you.” Then her eyes went back to the sea.

Her eyes glazed as she looked at the view.

“A little village once,” she said, “and now grown. …” She rose, taking

her napkin with her, and stood by the window.

“Did you quarrel with Timothy?” Clara asked shyly. “I should have.”

Mrs. Durrant came back from the window.

“It gets later and later,” she said, sitting upright, and looking down

the table. “You ought to be ashamed—all of you. Mr. Clutterbuck, you

ought to be ashamed.” She raised her voice, for Mr. Clutterbuck was

deaf.

“We ARE ashamed,” said a girl. But the old man with the beard went on

eating plum tart. Mrs. Durrant laughed and leant back in her chair, as

if indulging him.

“We put it to you, Mrs. Durrant,” said a young man with thick spectacles

and a fiery moustache. “I say the conditions were fulfilled. She owes me

a sovereign.”

“Not BEFORE the fish—with it, Mrs. Durrant,” said Charlotte Wilding.

“That was the bet; with the fish,” said Clara seriously. “Begonias,

mother. To eat them with his fish.”

“Oh dear,” said Mrs. Durrant.

“Charlotte won’t pay you,” said Timothy.

“How dare you …” said Charlotte.

“That privilege will be mine,” said the courtly Mr. Wortley, producing a

silver case primed with sovereigns and slipping one coin on to the

table. Then Mrs. Durrant got up and passed down the room, holding

herself very straight, and the girls in yellow and blue and silver gauze

followed her, and elderly Miss Eliot in her velvet; and a little rosy

woman, hesitating at the door, clean, scrupulous, probably a governess.

All passed out at the open door.

“When you are as old as I am, Charlotte,” said Mrs. Durrant, drawing the

girl’s arm within hers as they paced up and down the terrace.

“Why are you so sad?” Charlotte asked impulsively.

“Do I seem to you sad? I hope not,” said Mrs. Durrant.

“Well, just now. You’re NOT old.”

“Old enough to be Timothy’s mother.” They stopped.

Miss Eliot was looking through Mr. Clutterbuck’s telescope at the edge

of the terrace. The deaf old

Comments (0)