The Bodhisatta in Theravada Buddhism, Nico Moonen [christmas read aloud .txt] 📗

- Author: Nico Moonen

Book online «The Bodhisatta in Theravada Buddhism, Nico Moonen [christmas read aloud .txt] 📗». Author Nico Moonen

The Buddha taught in the Mahā-Parinibbana Sutta the following about worshipping to the highest degree:

“In full bloom are the twin Sāla trees … And celestial flowers and heavenly sandalwood powder from the sky rain down upon the body of the Tathāgata … and heavenly instruments make music in the air, out of reverence for the Tathāgata. Yet, not thus is the Tathāgata respected, venerated, esteemed, worshipped and honoured in the highest degree. But whatsoever bhikkhu or bhikkhuni, lay man or lay woman abides by the Teaching, lives uprightly in the Teaching, walks in the way of the Teaching, it is by him or her that the Tathāgata is respected, venerated, esteemed, worshipped and honoured in the highest degree.”[357]

And in the Kūtadanta Sutta (D.5) the following are mentioned as right sacrifices, in due order:

* Perpetual gifts kept up in a family where they are given specially to virtuous recluses.

* The putting up of a dwelling place (vihāra) on behalf of the Order.

* Taking refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma and (Ariya)Sangha.

* Taking up the five precepts with a trusting heart.

* The conversion of a hearer; his renunciation of the world and ordination as a monk.

* Observance of the monk’s Precepts.

* Fearlessness and confidence due to virtue.

* Sense-control.

* Mindfulness and full awareness.

* Contentedness.

* Conquest of the five Hindrances.

* Entering the Jhānas.

* Insight-knowledge.

* Attaining of Nibbāna.

There is no performance of a sacrifice higher than these! [358]

In this list there is no mention of giving the head or other parts of the body to the Buddha or to the Dhamma or to the Sangha. The killing of oneself is an extreme action and does not belong to the original teaching of the Buddha.

The conclusion is that the stories about the ten future Buddhas are later compositions. It is difficult to see how these stories could even be used for educational purposes. These stories could be said to be in conflict with the true teachings of the Buddha who taught the middle path avoiding the two extremes.

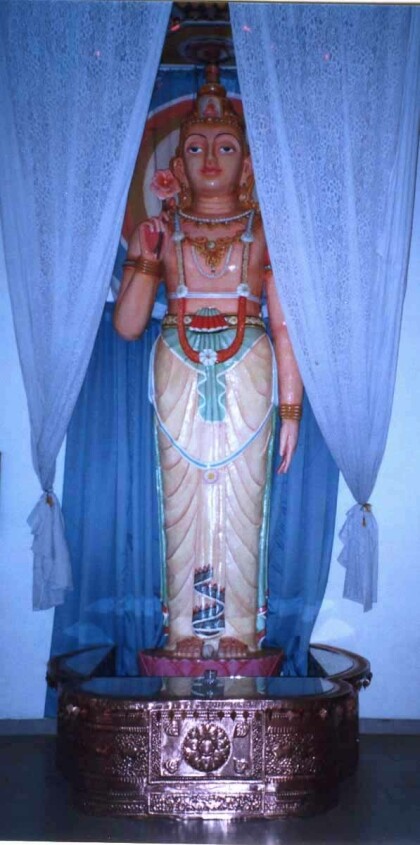

Fig. 8Bodhisatta Metteyya, Temple of the Army, Panagoda, Homagama, Sri Lanka (courtesy of Ven. R. Seewali)

In the Theravāda tradition there are three types of Bodhisattas, namely the Sāvaka Bodhisatta, the Pacceka Bodhisatta and the Mahā Bodhisatta. Each of these types will attain Enlightenment. The difference is that the Sāvaka Bodhisatta is an Arahant, he attains Enlightenment as a disciple of a Buddha. The Pacceka Bodhisatta attains Enlightenment through his own efforts but he is not able to teach the Dhamma to others. To become a Buddha takes a vast length of time and an enormous amount of effort. During that time the aspirant is called a Mahā Bodhisatta or in short, a Bodhisatta. He attains Enlightenment with his own effort and, in addition, he is able to teach the Dhamma to gods and men.

Before he decides to become the human being who will become a Buddha, the Mahā Bodhisatta could have already attained Nibbāna; that is to say he could have attained Enlightenment. He could have made an end of his suffering. But instead of that he gives it up and remains living as a common human, without special physical qualities. During immeasurably long periods of time he practises the ten perfections to become a teacher of gods and men.[360] The career of a Mahā Bodhisatta starts with his firm resolution to become a Buddha, together with the prediction of a living Buddha that his aspiration will succeed.

In Mahāyāna the ideal of Arahantship, the career of the Sāvaka Bodhisatta, was replaced by the ideal of the Bodhisattva, the Saint who out of compassion lives only for others. He aims at Buddhahood in order to liberate all other living beings. The Arahant is considered inferior to the Bodhisattva; for the Arahant is only a disciple-follower, the Bodhisattva tries to attain Buddhahood. The Bodhisattva has heard the Dhamma as well. Both Arahants and Bodhisattvas strive after the same goal: deliverance from suffering. It is also argued that the Arahant is selfish because he only aims at his own liberation. This conception of the Arahant is not correct. The Arahant has attained Perfect Enlightenment by following the teaching of the Buddha as a disciple. The ideal of Arahantship is not selfish at all. For Arahantship is gained only by eradicating all forms of selfishness. In Majjhima Nikāya 27 (Cūlahatthipadopama Sutta) a description can be found of one who aims at Arahantship. A summary of it follows here.

He gives up the killing of living beings. He has laid aside the cudgel and the knife and is modest and merciful, compassionate to all that lives. He gives up taking what is not given, and lives aloof, refraining from lust. He gives up lying, speaks the truth and deceives not the world. He gives up traducing speech. What he has heard here, he does not repeat elsewhere. He becomes one who unites the divided, encourages those who are friends, enjoys concord, and speaks words that make for concord. He gives up harsh talk. His words are pleasing to the ear, going to the heart, agreeable to many. He gives up frivolous chatter. He speaks what is true and meaningful, he is a speaker at the right time. He becomes one who refrains from injuring seeds and plants. He becomes one who refrains from accepting gold and silver, from accepting women and girls, bondsmen and bondswomen. He becomes one who refrains from accepting sheep and goats, poultry and pigs, cattle, fields and lands. He becomes one who refrains from the crooked acts of bribery, trickery and deception. He becomes one who refrains from cutting, killing, putting in bonds, robbing, plundering, and violence.[361]

The Arahant has given up and refrains from all that is mentioned here. And there is nothing selfish in it. Further, the Arahant has overcome every form of pride and egoism. He has practised the four great virtues of loving kindness (mettā), compassion (karuņā), sympathy (muditā), and equanimity (upekkhā). He or she is actively involved in helping others; it is the natural expression of having attained to Arahantship.[362]

The Arahant of Theravāda is sometimes compared with the Bodhisattva of Mahāyāna. Such comparison is misleading. In Mahāyāna it is said that the Bodhisattva has attained Nirvāņa but that he refrains from definitive extinction to help others. He becomes a saviour, who takes the burden of others upon him. According to Theravāda this is not possible. The Arahant, the one who has attained Nibbāna already in this life, will not be reborn again. The Bodhisattva of Mahāyāna will be reborn again and again. According to the teaching of Theravāda this means that he did not even attain the first stage of holiness, the entering of the stream to Nibbāna. Nor is it possible in Theravāda for the burden of one person to be carried by somebody else. Unwholesome kamma results cannot be removed by others, nor can good kamma results be transferred to others. The kammic results (vipāka) of good or bad deeds can be experienced only by that person themselves in this life or in future lives. Everybody must strive for his or her own liberation. It is not possible to gain salvation from suffering by the mercy of a Bodhisattva. Herein the doctrines of Theravāda and Mahāyāna differ from each other. It is true that in Theravāda petas (unhappy spirits) might be liberated from their unhappy existence by the transference of merit. The donator of the gifts will keep the fruits of the giving. But by the transference there will be created a divine counterpart of that gift. In that way the peta will be liberated from suffering.[363] This however is quite different from being redeemed from all suffering by a Bodhisattva. The Eightfold Path is available to everybody, not just by the extremely talented. Everybody must strive after Nibbāna themselves; everybody must exert their own willpower. If one permits all things to happen passively, without more ado, what will happen? Will it be possible to attain salvation in that way? – No! One must exert oneself. The saying “There are only empty phenomena” can be misinterpreted. It may lead many to inactivity, sloth and fatalism or to wrong conclusions. There is also the ability to choose our actions. If everything happened for no reason or deterministically, then nobody would be responsible for his or her own deeds.[364]

According to Mahāyāna everyone is already a Buddha by nature.[365] That means that everybody is a Bodhisattva, a being destined for perfect Enlightenment. But how can this be? It is true that everybody has the possibility to attain Enlightenment. But not everybody will reach that high goal. The Buddha taught that some persons will attain the goal, and others will not. It depends on the path one follows. If one takes the wrong way, he or she will never attain the goal. For, the Buddha is only a Teacher, not a Saviour. He shows us the way. But that way we must follow ourselves. Nobody else can go in our place. On one occasion this was clearly explained by the Buddha. A brahman asked him this question: “Do all disciples attain Nibbāna, or do some not attain it?” The Blessed One replied: “Some of my disciples, on being exhorted and instructed by me, attain the unchanging goal, Nibbāna; some do not attain it. – What is the reason? – A man might come and ask the way to Rājagaha. And you show him the way, show him how he has to walk. But that man, although he has been exhorted and instructed, might take the wrong road and go westward. Then a second man might come along wanting to go to Rājagaha. You instruct him in the same way. Exhorted and instructed thus, he might get to Rājagaha safely. What is the cause, what is the reason that, since Rājagaha does exist, since the way leading to Rājagaha exists, the one man may take the wrong road and go westward, while the other man may get to Rājagaha safely?” The brahman said: “In this matter I only show the way.” … “Even so, brahman, Nibbāna does exist, the way leading to Nibbāna exists and I exist as an adviser. But some of my disciples, on being exhorted and instructed thus by me, attain Nibbāna, and some do not. The Tathāgata only shows the way!”[366]

In Mahāyana the Bodhisattva is a saint with supernormal powers. But in Theravāda the Bodhisatta has not attained any stage of

Comments (0)