Puppets of Faith: Theory of Communal Strife (A Critical Appraisal of Islamic faith, Indian polity), BS Murthy [microsoft ebook reader .TXT] 📗

- Author: BS Murthy

Book online «Puppets of Faith: Theory of Communal Strife (A Critical Appraisal of Islamic faith, Indian polity), BS Murthy [microsoft ebook reader .TXT] 📗». Author BS Murthy

Notwithstanding Ghazni’s sack of Somnath, religious status quo still held good in Hindustan till the end of the 12th Century, when the sword of Allah wielded by Muhammad Ghuri firmly grounded the religion of the Arabs in the soil of the Arya Varta by enabling his lieutenant to establish the slave dynasty in Delhi. Thus was heralded the Muslim rule in India that was to last till the British signed off Bahadurshah Zafar the Last Mogul in the mid 19th Century.

While the oppressive Hindu phenomenon of untouchability worked well for the religion of the Arabs, it was as much the ‘social oppression’ as the ‘religious denial’ that would have made these outcastes feel, as if they were living in a no-man’s land in Hindustan. Moreso in Bengal, so it seems, where in droves, they had embraced the alien faith of the Islam that came with an odd cultural baggage of Arabia, which in the end assumed the proportions of a near exodus into the Muhammadan arena. After all, while the caste Hindus denied the outcastes their gods by keeping them at arm’s length from their mandirs, the Muslamans were prepared to share with them the precincts of their masjids for common prayers for Allah Ta’ala’s grace. This caste Hindu refusal to share even one amongst their pantheon of gods with the outcastes of Arya Varta, made the latter, as latter-day Musalmans, to shoulder the Islamic urge to grab its ‘land wings’ for Pakistan. Oh, what shortsightedness of Hindu pigheadedness!

Thus, by the time the political prop came to the Missionaries of the Christ in the form of the East India Company, in the late 18th Century, the homes of most of the disgruntled outcasts and vulnerable Hindus and / or both, were firmly in the Islamic tent. Even otherwise, the bottom line of the alien religious appeal to the populace of Hindustan is that Islam and the Christianity could only impinge upon the fringes of its polity, that too when the rulers belonged to the respective religious dispensations. After all, this is understandable since man tends to weigh the temporal advantages more than the spiritual benefits when it comes to embracing a new religion, and depending on the state of evolution in a given society or commune, the factors that prompt one’s conversion change from time to time.

Nonetheless, as East India Company and later the British Viceroys were interested more in commercial exploitation than in religious conversions, the evangelists could not harvest as many souls, as Pope John Paul II had paraphrased it in recent times, as they would have loved to. Yet the Christianity made its Indian mark in remarkable ways, more so being instrumental in introducing secular education that ushered in social reengineering in an otherwise stagnant Hindu society, the sad relic of a once vibrant Upanishadic polity. Eventually though, what with so much reformist water having flowed down the untouchable bride, of course, pumped by the western educated Hindus leading up to the independence struggle and beyond, the caste color of Hindustan began to acquire a new shade albeit imperceptibly.

It was only time before modernism became the new mantra of upward mobility, and the western education, the preferred route to social savvy in the Indian society, but as Islam is conceptually antagonistic to both, at last, it lost its erstwhile sway over even among the disaffected harijans, nay dalits, who, instead, tended to seek the Standard of the Christ as a benign brand equity. Thus, it is no wonder that the Christian salvation had become the natural selection for the Hindu fringes, if only seduced with the right inducements from the Catholic Church.

Nevertheless, unlike the Brahmanical indifference of yore to those unabated conversions into Islam, the Hindu mood of the day is in no mood to brook the compulsive Christian urge to proselytize, by means fair or foul. This justifiable Hindu resentment against the Christian zeal to convert others into its religious creed had unfortunately led to unjustifiable atrocities on the evangelists on occasion.

All said and done the so-called revealed religions that supposedly preach the pure message, or purportedly show the straight path, have failed to touch the mainstream of the Hindu polity. And that is in spite of the unceasing efforts of their proselytizers and the presence of their converts in their midst for a millennium! It is thus, the surprising resistance of the Hindu dharma to the dogma of Semitic religions, unlike the political capitulation of India to foreign forces, would be worth probing for the fault lines in the proselytizing faiths.

The assumption of the Christians is that only the Gospel could enable man’s salvation, and that Jesus, the Son of God, only could intervene on behalf of man on the Day of Reckoning. The novel path of salvation through the Christianity that Jesus showed would have surely excited the Christian missionaries, and their desire to share their noble creed with the others is unexceptionable. But for the Christians to imagine that there could be no salvation sans their God’s Son betrays the credulity of their minds at best, and their ignorance of the Hindu philosophy’s sophistication at worst. It is a different matter though, that for the orthodox Jews, Jesus was a Judaic renegade, and for the idolatrous Arabs, Muhammad was but a deviant, and so on, which brings to the fore the fallacy of prophetic glorification.

Though it was the unwavering belief in Jesus that enabled the Christian missionaries, in spite of centuries of persecution, to spread his word on the continent and elsewhere that kept the Christianity alive to start with, the eclipse of the Greco-Roman Gods in the heart of the Roman Empire at its expense was achieved more through the conversion of Emperor Constantine than by the miracles of the Son of God and his anointed Saints. Whatever, this Christian conviction of salvation coupled with the mistaken belief that the Hindu souls were languishing for want of the message from the Messiah, which could have brought St. Thomas to the Malabar Coast half a century after Jesus had died on the Cross.

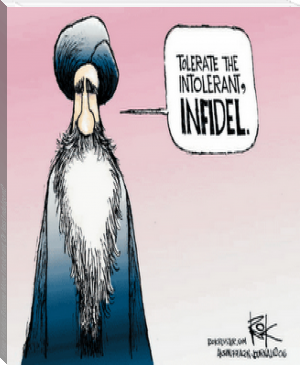

On the contrary, with the sword of Allah in one hand and Muhammad’s Quran in the other, the Caliphs of Islam set out to pillage the world with an army of zealots, who had their eyes on plunder or Paradise, and / or both. Whatever, it was the good fortune of Islam, and the misfortune of its adversaries, that its adherents encountered little or no resistance from the nations of the world, by then exhausted after centuries of wars, to spread its wings all across. Oh, how one religion’s food had turned out to be other religions’ poison!

If the credo of the Christianity is courting other religious souls in covetous ways, the creed of the Musalman has been to turn the kafirs of the world into servants of their God, and by extension admirers of their prophet. After the destruction of the idols of the Arabia, the mandirs of India that the Musalmans might have heard about should have raised their hopes of mundane plunder, even as they would have outraged their religious sensitivity. Muhammad’s allergy for the idols at the Kabah was to turn out, some three centuries later, to be the nightmare of the Hindu deities in their resplendent mandirs. The anecdote quoted by M J Akbar in ‘The Shade of the Swords’, published by Roli Books, is illustrative.

“The story of the Muslim conquest of central India may have begun with a misunderstanding: one man’s pronunciation can become another man’s poison. The three most revered pagan goddesses of pre-Islamic Mecca were Al Lat, Al Uzza, and Manat, denounced in the Quran as false deities and the source of the infamous controversy about the alleged ‘Satanic Verses’. According to an old belief, when the Prophet smashed the idols of the Kaaba, the image of Manat was missing: it had been secreted away, and sent in a trading ship to a port-town in India called Prabhas, which imported Arab horses. According to this belief, idol-worshippers built a temple to Manat, and renamed the place So-Manat, or Somnath. The warrior king Mahmud, who built an empire from the Afghan city of Ghazni, waged the first jihad in the heart of India. His most famous raid was the one in which he destroyed the idol at Somnath and carried away enough booty to appease avarice.”

However, the very fact that Mahmud raided the temples of Mathura, Thanesar and Kannauj before plundering Somnath would leave one wondering whether it was not a Muslim rationalization of the gruesome killing of over ‘fifty thousand’ souls, possibly, including a thousand Brahman priests, in the temple of So-Manat? But, what is relevant is the reported hope of Mahmud that once the idol of Somnath was captured and destroyed, the Hindus would become Muhammadans, a la Meccans. But, that didn’t happen, and as though to signify the symbolism of Somnath to the Hindu ethos, even the secular government of Nehru’s India thought it fit that the temple should be rebuilt.

What was in the Hindu dharma that soured St. Thomas’ dream to proselytize the polity and belied Mahmud’s hopes to see a Muslim India? The logical and rational answer would be that the Hindus are neither heathens as assumed by the Christians nor are they idolaters as presumed by the Musalmans. On the other hand, as against the single-scripture wisdom of the Abrahamic Orders and the dogmas of their prophets, the Hindu sanātana dharma is a spiritual way of life with an imbibed philosophical ethos that is steeped in deep-rooted culture and tradition. Thus, in terms of reach and approach, the straight but narrow paths of Judaism, the Christianity, not to speak of Islam, appear like by-lanes of bigotry compared to the Highway of Hindu Spirituality, exemplified by the dictum of vasudhaiva kutumbakam – (world is one family).

However, the irony of Hinduism is that this laudable premise was neither passed on to the outside world, and what is worse, nor put in practice in its homeland either, if not why were there those untouchables and the downtrodden in the Hindu backyard? After all, notwithstanding their hallowed precepts, doublespeak and double standards seem to be the common features of all the religions. Just the same, while the Semitic religions are faith driven, the sanātana dharma is philosophical in its orientation, and that enables the Hindus to probe the vicissitudes of life unbound by any scriptural dogma. And this has always been the strength of Hinduism notwithstanding its Achilles’ heel of caste discrimination for possible course correction, all by itself, which, in time, led to the birth of the likes of Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism.

It is in this context that the Roberto Baggio episode is to be seen. The Italian footballer, dejected as he was owing to his penalty goof-up that cost his country the World Cup, reportedly turned to Buddhism for solace for he felt that the Christian dogma had no philosophical inputs in it to face of the vicissitudes of life. That Jesus died for the sinners won’t help his faithful in any way to handle their own predicaments. After all, the feature of the Semitic religious faiths is the dogmatic belief sustained by habit while spirituality epitomizes the search for the self in this world and beyond.

Whatever others might think of the Hindus of the day, their forebears once believed, as Americans do now, as Alberuni observed that,

“there is no country but theirs, no nation like theirs, no kings like theirs, no religion like theirs, no

Comments (0)