Puppets of Faith: Theory of Communal Strife (A Critical Appraisal of Islamic faith, Indian polity), BS Murthy [microsoft ebook reader .TXT] 📗

- Author: BS Murthy

Book online «Puppets of Faith: Theory of Communal Strife (A Critical Appraisal of Islamic faith, Indian polity), BS Murthy [microsoft ebook reader .TXT] 📗». Author BS Murthy

If anything, as and when the hoped-for Hindu renaissance does take place, the tag of three thousand years old culture would be added to the above in their Hall of Fame.

Herein lay the Christian inability to proselytize India and the Muslim failure to attract the caste Hindus into the Islamic fold.

W. W. Hunter, aided by the Gibbonian insight, throws light on the nature of the mono and polytheism in The Indian Musalmans, published by Rupa & Co, India, thus:

“Yet many English Officers have gone through their service with a chronic indignation against the Muhammadan for refusing to accept the education which we have tried to bring to every man’s door. The felicity with which the rest of the population acquiesced in it made this refusal more odious by contrast. The plaint Hindu knew no scruples, and we could not understand why the Muhammadan should be troubled with them. But the truth is, that we overlooked a distinction as old as the religious instinct itself, the distinction which in all ages and among all nations has separated polytheism from the worship of One God. Polytheism, by multiplying the objects of its followers’ adoration, divides its claims on their belief.

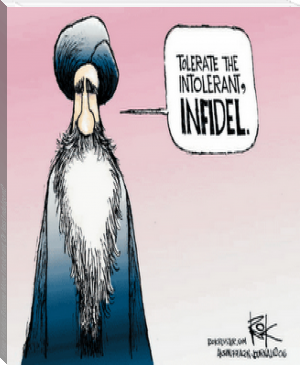

What Gibbon finely said of the Greeks, applies at this moment with more than its original force to the Hindus: ‘Instead of an indivisible and regular system which occupies the whole extent of the believing mind, the mythology of the Greeks was composed of a thousand loose and flexible parts, and the servant of the gods was at liberty to define the degree and measure of his religious faith.’ The Muhammadans have no such licence. Their creed demands an absolute, a living, and even an intolerant belief; nor will any system of Public Instruction, which leaves the religious principle out of sight, ever satisfy the devout follower of Islam.”

Why not, the caste Hindus, prone to be biased against those borne into the so-called lower castes, yet are not abhorrent of the lesser gods worshipped by them, though they themselves ascribe no divinity to these minor deities that dubbed as kshudra devatās. While that portrays the religious tolerance of the Hindus to differing faiths, sadly it betrays their cultural intolerance towards the deprived fellow-human beings, upon which the Islam and the Christianity, espousing an egalitarian doctrine, had made inroads into the Indian religious milieu.

Yet, it is the paradox of the Semitic faiths in that while vouching for the selfsame God, who is believed to have enshrined the Torah, inspired the Gospel and gave the Quran, it was the Christians that ran the Crusades against the Musalmans, who had earlier oppressed the Jews. While the unfortunate Jews suffered again at the Christian hands in the European lands in several pogroms before the Holocaust, given the Hindu tolerance for other religious dispensations, it was in India that they could breathe easy without let or hindrance pursuing their faith; which fact was gratefully acknowledged by the modern state of Israel.

But when it comes to the peoples of the Books, though all of them repose their faith in the selfsame God but as the dogmas of their cults vary, they tend to be at each others’ throats, and in what can be said as the acme of the Abrahamic religious intolerance, the Ahmadias ‘n Shias of Pakistan and the Shias of Iraq have come to suffer at the Sunni hands as the worst victims of the Islamic dogma.

Wish the Semitic scriptures contained some philosophy as well!

Chapter 19

India in Coma

The zeal of the Arabs to spread Muhammad’s word that catered to their innate urge to plunder, which for Edward Gibbon made Islam ‘the profitable religion of Arabia’, obliterated the great cultures of the time, occasioned by his thesis that “the Koran inculcates, in the most absolute sense, the tenets of fate and predestination, which would extinguish both industry and virtue, if the actions of man were governed by his speculative belief.”

Whatever, after the initial fanatical momentum of the booties, the Arabs, bereft of any political culture to name began to yield the pan-Islamic temporal ground to the very peoples - the Turks, the Persians and the Afghans - they had coerced into their faith. It’s the irony of history that these very peoples, subjugated by the Arabs to the detriment of their gods, had furthered the cause of Islam with the swords of their own, of course, fired by their ambition and fuelled by the newfound religious zeal. No less paradoxically, as these converts came to undermine the Arab authority in the emerging umma, the purveyors of the faith retreated into their tents, which deprived them of any further partake in the affairs of the Islamic world, that is till the petrodollars made them the masters of the domain of the Musalmans once again.

On the other hand the Brahmans, the authors of the Indian caste system that inflicted grievous wounds on the body polity of the grand land, continued to hold sway over the Hindu social consciousness with their intellectual savvy and religious orthodoxy that is well after the Arabs had resigned to their inglorious fate. Besides, in the Vedic times, the Brahmans were well adept at warfare too, as the exploits of the Dronacharyās, Aswathamās et al in the epic battle of Maha Bhārata would illustrate. Even in the earlier Ramayana times, Parashurama, Lord Vishnu’s avatar as a Brahman, emphasized the Brahmanical ethos thus:

agratas chaturō vēdān / Spar at not a Vedic soul

prushtash saran dhanō / Armed to the teeth as well

idam kshātram idam brāhmayam / Brain ’n brawn as thus combined

sepādapi sarā dapi. / Curse I might or subdue thee.

While Arya Varta’s political fabric in myriad social colors, woven with the wharf of varna and the weft of dharma, was worn by varied caste groups in their accorded custom (swadharma), ordained by the country code (sanātana dharma), the power of the Hindu State willed in enforcing the dharmic order in all its manifestations. If each caste were to adhere to its own dharma without let or hindrance, so it was assumed, all was well with the State itself.

However in time, what with the gradual decline of the great Hindu empires giving way to tiny kingdoms and banana republics, internecine battles for the sole domination of Arya Varta or as much of it as within reach, became the norm rather than an exception. Understandably, the Brahmans could not have remained immune to the political turmoil around, which would have threatened their cultural hegemony that they had inherited, and so were embroiled in intrigues with a view to retain their hold on the political handles of what they came to call as the karma bhōmi.

But with the diminishing stature of the rulers of the land, their own political diminution was not far off, and so they too ceased to be the wise ministers they used to be. So, when Mahmud’s father was building border roads in Afghanistan to enable his son to war his way into Somnath, there was no Chānakya in the Brahman ranks then to build the political bridges in India. And adding to the woes of the Arya Varta, its kshatriyas too, for far too long weren’t producing Vikramādityas of yore either.

Thus, the decline of the Brahmanical sagacity and the pettiness of the kshatriya princes, together weakened the Indian political State further, setting in motion the Hindu socio-political degeneration that insensibly led the vexed multitudes into their regional shells of self-destruction. It was into this India in coma that the Afghan Armageddon of Mahmud of Ghazni had a cakewalk for unleashing an era of loot and plunder in the land of sanātana dharma.

The episode that shook the Hindus and shaken their pride like none else is thus narrated in Romila Thapar’s A History of India published by Penguin India.

“Temples were depositories of vast quantities of wealth, in cash, golden images, and jewellery – the donations of the pious and these made them natural targets for a non-Hindu searching for wealth in northern India. Mahmud’s greed for gold was insatiable. From 1010 to 1026 the invasions of Mahmud were directed to temple towns – Mathura, Thanesar, Kanauj, and finally Somnath. The concentration of wealth at Somnath was renowned, and consequently it was inevitable that Mahmud would attack it. Added to the desire for wealth was the religious motivation, iconoclasm being a meritorious activity among the more orthodox followers of the Islamic faith. The destruction at Somnath was frenzied, and its effect was to remain for many centuries in the Hindu mind and to colour its assessment of the character of Mahmud, and on occasion of Muslim rulers in general. A thirteenth-century account from an Arab source refers to this event.

‘Somnat – a celebrated city of India situated on the shore of the sea and washed by its waves. Among the wonders of that place was the temple in which was placed the idol called Somnat. This idol was in the middle of the temple without anything to support it from below, or to suspend it from above. It was held in the highest honour among the Hindus, and whoever beheld it floating in the air was struck with amazement, whether he was a Musulman or an infidel.

The Hindus used to go on pilgrimage to it whenever there was an eclipse of the moon and would then assemble there to the number of more than a hundred thousand. They believed that the souls of men used to meet there after separation from the body and that the idol used to incorporate them at its pleasure in other bodies in accordance with their doctrine of transmigration. The ebb and flow of the tide was considered to be the worship paid to the idol by the sea. Everything of the most precious was brought there as offerings, and the temple was endowed with more than ten thousand villages. There is a river (the Ganges), which is held sacred, between which, and Somnat the distance is two hundred parasangs. They used to bring the water of this river to Somnat every day and wash the temple with it. A thousand Brahmans were employed in worshipping the idol and attending on the visitors, and five hundred damsels sung and danced at the door - all these were maintained upon the endowments of the temple.

The edifice was built upon fifty-six pillars of teak covered with lead. The shrine of the idol was dark but was lighted by jewelled chandeliers of great value. Near it was a chain of gold weighing two hundred mans. When a portion (watch) of the night closed, this chain used to be shaken like bells to rouse a fresh lot of Brahmans to perform worship. When the Sultan went to wage religious war against India, he made great efforts to capture and destroy Somnat, in the hope that the Hindus would become Muhammadans. He arrived there in the middle of … December A. D. 1025.

The Indians made a desperate resistance. They would go weeping and crying for help into the temple and then issue forth to battle and fight till all were killed. The number of slain exceeded 50,000. The king looked upon the idol with wonder and gave orders for the seizing of the spoil and the appropriation of the treasures. There were many idols of gold and silver and vessels set with jewels, all of which had been sent there by the greatest personages in India. The value of the things found in the temple and of the idols exceeded twenty thousand dinars.

When the king asked his companions what they had to say about the marvel of the idol, and of its staying in the air without prop or support, several maintained that it was upheld by some hidden support. The king directed a person to go and feel all around and above and below it with a spear, which he did but met with no obstacle. One of the attendants then stated his opinion that the canopy was made of loadstone, and the

Comments (0)