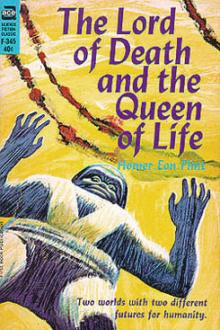

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

Kinney’s diagnosis proved correct. Smith knew his business; the machinery was finished in a hurry and done right. However, when it came to fitting the outfit into a suitable sky-car, Kinney was obliged to call in an architect. That accounts for E. Williams Jackson. At the same time, it occurred to the doctor that they would need a cook. Mrs. Kinney had refused to have anything whatever to do with the trip, and so Kinney put an ad in the paper. As luck would have it, Van Emmon, the geologist, who had learned how to cook when he first became a mountaineer, saw the ad and answered it in hope of adventure.

The doctor himself, besides his training in the mental and bodily frailities of human beings, had also an unusual command of the related sciences, such as biology. Smith’s specialties have already been named; he could drive an airplane or a nail with equal ease. Van Emmon, as a part of his profession, was a skilled “fossilologist,” and was well up in natural history.

As for E. Williams Jackson—the architect was also the sociologist of the four. Moreover, he had quite a reputation as an amateur antiquarian. Nevertheless, the most important thing about E. Williams Jackson was not learned until after the visit to Mercury, after the terrible end of that exploration, after the architect, falling in a faint, had been revived under the doctor’s care.

“Gentlemen,” said Kinney, coming from the secluded nook among the dynamos which had been the architect’s bunk; “gentlemen, I must inform you that Jackson is not what we thought.

“He—I mean, she—is a woman!”

Which put an entirely new face upon matters. The three men, discussing it, marveled that the architect had been able to keep her sex a secret all the time they were exploring at Mercury. They did not know that none of E. Williams Jackson’s fellow architects had ever guessed the truth. Ambitious and ingenious, with a natural liking for house-planning, she had resolved that her sex should not stand in the way of success.

And when she finally came to herself, there in her bunk, and suspected that her secret was out—instead of shame or embarrassment she felt only chagrin. She walked, rather unsteadily, across the floor of the great cube-shaped car to the window where the three were standing; and as they quietly made a place for her, she took it entirely as a matter of course, and without a word.

The doctor had been speaking of the peculiar fitness of the four for what they were doing. “And if I’m not mistaken,” he went on, “we’re going to need all the brains we can pool, when we get to Venus.

“I never would have claimed, when we started out, that Mercury had ever been inhabited. But now that we’ve seen what we’ve seen, I feel dead sure that Venus once was peopled.”

The four looked out the triple-glazed vacuum-insulated window at the steadily growing globe of “Earth’s twin sister.” Half in sunlight and half in shadow, this planet, for ages the synonym for beauty, was now but a million miles away. She looked as large as the moon; but instead of a silvery gleam, she showed a creamy radiance fully three times as bright.

“Let’s see,” reflected the geologist aloud. “As I recall it, the brightness of a planet depends upon the amount of its air. That would indicate, then, that Venus has about as much as the earth, wouldn’t it?” remembering how the home planet had looked when they left it.

The doctor nodded. “There are other factors; but undoubtedly we are approaching a world which is a great deal like our own. Venus is nearly as large as the earth, has about nine-tenths the surface, and a gravity almost as strong. The main difference is that she’s only two-thirds as far from the sun as we are.”

“How long is her day?” Smith wanted to know.

“Can’t say. Some observers claim to have seen her clearly enough to announce a day of the same length as ours. Others calculate that she’s like Mercury; always the same face toward the sun. If so, her day is also her year—two hundred and twenty-five of our days.”

Van Emmon looked disappointed. “In that case she would be blistering hot on one side and freezing cold on the other; except,” remembering Mercury, “except for the ‘twilight zone,’ where the climate would be neither one nor the other, but temperate.” He pointed to the line down the middle of the disk before them, the line which divided the lighted from the unlighted, the day from the night.

The four looked more intently. It should be remembered that the very brilliance of Venus has always hindered the astronomers; the planet as a whole is always very conspicuous but its very glare makes it impossible to see any details. The surface has always seemed to be covered by a veil of hazy, faintly streaked vapor.

Smith gave a queer exclamation. For a moment or two he stared hard at the planet; then looked up with an apologetic grin.

“I had a foolish idea. I thought—” He checked himself. “Say, doesn’t Venus remind you of something?”

The doctor slowly shook his head. “Can’t say that it does, Smith. I have always considered Venus as having an appearance peculiarly her own. Why?”

The engineer started to answer, stopped, thought better of it, and instead pointed out the half that was in shadow. “Why is it that we can make out the black portion so easily?”

Kinney could answer this. “The fact is, it isn’t really black at all, but faintly lighted. Presumably it is star-shine.”

“Star-shine!” echoed the architect, interested.

“Just that. You see,” finished the doctor, “if that side is never turned toward the sun, then it must be covered with ice, which would reflect the star—”

“Ah!” exclaimed Smith with satisfaction. “I wasn’t so crazy after all! My notion was that the whole blamed thing is covered with ice!”

It looked reasonable. Certainly the entire sphere had a somewhat watery appearance. It prompted the geologist to say:

“Kinney—if that reflection is really due to ice, then there must be plenty of water vapor in the air. And if that’s the case—”

“Not only is life entirely possible,” stated the doctor quietly, “but I’ll bet you this sky-car against an abandoned soap-stone mine that we find humans, or near-human beings there when we land tomorrow!”

II SPEAKING OF VENUSThe architect was still dressed in the fashionably cut suit of men’s clothes she had worn while in the car. Van Emmon thought of this when he said, somewhat awkwardly:

“Well, I’m going to fix something to eat. It’ll be ready in half an hour, Miss—er—Jackson.”

She looked at him, slightly puzzled; then understood. “You mean to give me time to change my clothes? Thanks; but I’m used to these. And besides,” with spirit, “I never could see why women couldn’t wear what they choose, so long as it is decent.”

There was no denying that hers were both becoming and “decent.” Modeled after the usual riding costume, both coat and breeches were youthfully, rather than mannishly, tailored; and the narrow, vertical stripe of the dark gray material served to make her slenderness almost girlish. In short, what with her poet-style hair, her independent manner and direct speech, she was far more like a boy of twenty than a woman nearing thirty.

She walked with Van Emmon, dodging machinery all the way, across the big car to the little kitchenette over which he had presided. There, to his dismay, the girl took off her coat, rolled up her sleeves, and announced her intention of helping.

“You’re a good cook, Van—I mean, Mr.—”

“Let it go at Van, please,” said he hastily. “My first name is Gustave, but nobody has ever used it since I was christened.”

“Same with my ‘Edna,’ she declared. “Mother’s name was Williams, and I was nicknamed ‘Billie’ before I can remember. So that’s settled,” with great firmness. The point is—Van—you’re a good cook, but everything tastes of bacon. I wish you’d let me boss this meal.”

He looked rebellious for an instant, then gave a sigh of relief. “I’m really tickled to death.”

A little later the doctor and Smith, looking across, saw Van Emmon being initiated into the system which constructs scalloped potatoes. Next, he was discovering that there is more than one way to prepare dried beef.

“For once, we won’t cream it,” said E. Billie Jackson, dryly, as Van Emmon laid down the can-opener. “We’ll make an omelet out of it, and see if anything happens.”

She was already beating the eggs. He cut up the meat into small pieces, and when he was finished, took the egg-beater away from her. He turned it so energetically that a speck of foam flew into his face.

“Go slow,” she advised, nonchalantly reaching up with a dish-towel and wiping the fleck away. Whereupon he worked the machine more furiously than ever.

Soon he was wondering how on earth he had come to assume, all along, that she was not a woman. He now saw that what he had previously considered boyishness in her was, in fact, simply the vigor and freshness of an earnest, healthy, energetic girl. It dawned upon him that her keen, gray eyes were not sharp, but alert; her mouth, not hard, but resolute; her whole expression, instead of mannish, just as womanly as that of any girl who has been thrown upon her own resources, and made good. He soon found that his eyesight did not suffer in any way because he looked at her.

“Now,” she remarked, in her businesslike way, as she placed the brimming pan into the oven, “I suppose that I’ll hear various hints to the effect that a woman has no business trying to do men’s stunts. And I warn you right now that I’m prepared to put up a warm argument!”

“Of course,” said the geologist, with such gravity that the girl knew he didn’t mean it; “of course a woman’s place is in the home. Surrounded by seventeen or eighteen children, and cooking for that many more hired men besides, she is simply ideal. We realize that.”

“Then, admitting that much, why shouldn’t a woman be as independent as she likes? Think what women did during the war; remember what a lot of women are doctors and lawyers! Is there any good reason why I couldn’t design a library as well as a man could?”

“None at all,” agreed Van Emmon, handing over the dish of chopped meat. The girl carefully folded the contents into the now spongelike omelet as he went on: “By the way, a neighbor of mine told me, just before I left, that he was having trouble with a broken sewer. How’d you like to—”

“About as well as you’d like to darn socks!” she came back, evidently being primed for such comments. She took a look at the potatoes, and then permitted the geologist to open their sixth can of peaches. “I must say they’re good,” she admitted, as she noted the eagerness with which he obeyed.

Bread and butter, olives, coffee and cake completed that meal. The table was set with more care than usual, a clean cloth and napkins being unearthed for the occasion. When Smith and Kinney were called, both declared that they weren’t hungry enough to do justice to it all.

“It’s just as well you weren’t very hungry,” commented Billie, as she finished giving each of them a second helping of the potatoes. “There’s

Comments (0)