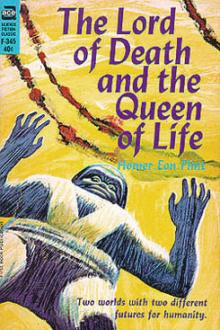

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life, Homer Eon Flint [ebook reader .txt] 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

“Say, I never thought of it before, Miss—er—Miss Billie,” said Smith coloring; “but you eat just as much as a man!”

“Ye gods, how shocking!” she jeered. “Come to think of it, Smith, you eat MORE than a woman!”

The doctor’s face grew red with some suppressed emotion. After a while he said soberly: “I’ll tell you what’s worrying Smith. He’s afraid that women, having suddenly become very progressive, will forge entirely ahead of men. You understand—having started, they can’t stop. And I must admit that I’ve thought seriously of it at times myself.”

“Me too,” added Van Emmon earnestly. “I have the same feeling about it that an elderly man must have when he sees a young one get on the job. Instead of being glad that the women are making good, I sort of resent it.”

“I knew it!” exclaimed the girl delightedly. “But I never heard a man admit it before!”

“Perhaps it isn’t as serious as we think,” said the practical Smith, scraping the bottom of the potato pan. “I believe that the progress of women may have a fine effect upon men, making us less self-satisfied, and more alert. For one thing,” glancing about the cube, “we’ve got to clean up a bit, now that we know you’re a woman!”

The architect’s eyes flashed. “Because you know mighty well I’ll light in and do it myself, if you don’t; that’s what you mean! Please take notice that I’m to be respected, not because of what I AM, but because of what I can DO!”

“In behalf of myself and companions, I surrender!” said the doctor gallantly. Then he instantly added: “And yet, even when we are actually chivalrous, we are disregarding your desire to be appreciated for what you are worth. Pardon me, Miss Billie; I’ll not forget again.

“At the same time, my dear,” remembering that he had a daughter of his own, nearly the builder’s age, “we men have come to think of women primarily as potential mothers, and secondarily as people of affairs. And considering that motherhood is something that is denied to us lords of the earth—”

“For which we can thank a merciful Providence,” interjected the girl solemnly.

“Considering this—excuse my seriousness—really amazing fact, you can’t blame us for expecting women to fulfil this vital function before taking up other matters.”

“Yes?” remarked the girl, watching the peaches with anxious eye as Van Emmon helped himself. “Funny; but I always understood that the first function of man was to father the race; yet, invariably the young fellows try to make names for themselves before, not after, they marry!”

“Scalped!” chuckled Van Emmon, as the doctor hid his discomfiture behind a large piece of cake. “You may know a lot about Venus, doc, but you don’t know much about women!”

“Speaking about Venus,” Smith was reminded, “we may learn something bearing upon the very point we have been discussing if Kinney’s right about the inhabitants.”

The doctor nodded eagerly. “You see, if there’s people still alive on the planet, they’re probably further advanced than we on the earth. Other things being equal, of course. Being a smaller planet than ours, she cooled off sooner, and thus became fit for life earlier. And having been made from the same ‘batch,’ to use Van’s expression, that Mercury and all the rest were, why, in all likelihood evolution has taken place there much the same as with us, only sooner.

“I should expect,” he elaborated largely, “that we shall find the inhabitants much the same as we humans, only extremely civilized. It may be that they are as far above us as we are above monkeys.”

Smith broke in by quoting an astronomer who contended that Venus kept only one face toward the sun. “Maybe she always did, Kinney.”

The doctor shook his head. “See how perfectly round she is? No oblateness whatever. It proves that she once revolved, otherwise she’d be pear-shaped, from the sun’s pull.”

There was a short silence, during which Billie concluded that the only scraps left would be the coffee-grounds. Then Van Emmon pushed away from the table, got to his feet, stretched a little to relieve his nerves, and said:

“Well, whatever we find on Venus, I hope the women do the cooking!”

III THE FIRST VENUSIANWhen the sky-car was within a thousand miles of the surface, Smith adjusted the currents so that the floor was directed downward. The four changed from the window to the deadlight, and watched the approaching disk with every bit of the excitement and interest they had felt when nearing Mercury.

The doctor had warned them that the heavy atmosphere which Venus was known to possess would prevent seeing as clearly as in the case of the smaller planet. All were much disappointed, however, to find that they were still unable to make out a single definite detail. The great half-shining, half-black world showed nothing but that vaguely streaked, ice-like haze.

There was something very queer about it all. “Strange that we should see no movement in those clouds,” mused the doctor aloud. “That is, if they really are clouds.”

Van Emmon already doubted it. “Just what I was thinking. There ought to be terrific winds; yet, so far as I have seen, there’s been nothing doing anywhere on the surface since we first began to observe it.”

After a while the doctor put away his binoculars and rubbed his eyes. “We might as well descend faster, Smith. Can’t see a thing from here.”

Unhindered by air to impede its progress the sky-car had been hurtling through space at cometary speed. Now, however, Smith added the power of the apparatus to the pull of the planet, so that the disk began to rush toward them at a truly alarming rate. After a few seconds of it Billie found herself unconsciously moving to the side of the geologist.

He looked down at her, understood, and flushed with pleasure. “There’s no danger,” he confidently assured her, with the result that, her courage fortified, the girl moved back to her place again. Van Emmon inwardly kicked himself.

So deceptive was that peculiar fogginess Smith throttled their descent as soon as they had reached the point where the planet’s appearance changed from round to flat. They were headed for the line which marked the boundary of the shadow. This gray “twilight zone” was three or four hundred miles in width; on the right of it—to the east—the dazzling surface of that sunlit vapor contrasted sharply with the all but black mistiness of the starward side. Clearly the zone ought to be temperate enough.

Down they sank. As they came nearer a curious pinkish tint began to show beneath them. Shortly it became more noticeable; the doctor gave a sudden grunt of satisfaction, and Smith stopped the car.

A minute later the doctor had taken a sample of the surrounding ether through his laboratory test-vestibule; and shortly announced that they were now floating in air instead of space.

“Good deal like ours back home, too”—exultingly. “Pretty thin, of course.” He made a short calculation, referring to the aneroid barometer which was mounted on the outer frame of a window, and said he judged that their altitude was about five miles.

The descent continued, Smith using the utmost caution. The other three kept their eyes glued to the deadlight; and their mystification was only equaled by their uneasiness as that motionless, bleary glaze failed absolutely to show anything they had not seen a thousand miles higher. Not a single detail!

“It reminds me,” said the girl in a low voice, “of something I once saw from the top of a hill. It was the reflection of the sun from the surface of a pond; not clear water, but covered with—”

“Good Heavens!” interrupted Van Emmon, struck with the thought. “Can it be that the whole planet is under water?”

Beyond a doubt his guess was justified. There was an oily smoothness about that dazzling haze which made it remarkably like a lake of still and rather dirty water under a bright sun.

But the doctor said no. “Any water I ever heard of would make clouds,” said he; “and we know there’s air enough to guarantee plenty of wind. Yet nothing seems to be in motion.” He was frowning continually now.

It was Billie who first declared that she saw the surface. “Stop,” she said to Smith evenly, and he instantly obeyed. All four gathered around the deadlight, and soon agreed that the peculiarly elusive skin of the planet was actually within sight. However, it was like deciding upon the distance of the moon—as easy to say that it were within arm’s reach as a long ways off.

The doctor went to a window. There he could look out upon the sun, a painfully bright object much larger than it looks from the Earth. It was just “ascending,” and half of it was below the horizon. A blinding streak of light was reflected from a point on the surface not far from the cube. Shading his eyes with his hand the doctor could see that the mysterious crust was absolutely smooth.

On the opposite side of the car the horizon ended in a sunrise glow of a slightly greenish radiance. From that side the pinkish tint of the surface was quite pronounced.

Before going any lower the doctor, struck with an idea, declared: “We always want to remember that this car is perfectly soundproof. Suppose we open the outer door of the vestibule. I imagine we’ll learn something peculiar.”

It was possible to open this door without touching the inner valves, using mechanism concealed within the walls. The moment it was done—the door faced the “north”—pandemonium itself broke loose. A most terrific shrieking and howling came from the outside; it was wind, passing at a rate such as would make a hurricane seem a mere zephyr. The doctor closed the door so that they could think.

“It’s the draft,” he concluded; “the draft from the sun-warmed side to the cold side.”

As for Van Emmon, he was getting out a rope and a heavy leaden weight. On the rope he formed knots every five feet, about twenty of them; and after getting into one of the insulated, aluminum-armored and oxygen-helmeted suits with which they had explored Mercury, he locked himself on the other side of the inner vestibule door and proceeded to “sound.”

To the amazement of all except Billie “bottom” was reached in less than twenty feet. “I thought so,” she said with satisfaction; but she was not at ease until Van Emmon had returned in safety from that booming, whistling turmoil.

His first remark upon removing his helmet almost took them off their feet. “The point is,” said he, throttling his excitement—“the point is, the rope was nearly jerked out of my hands!

“Understand what I mean? The surface is REVOLVING!”

This upset every idea they had had; it never occurred to any of them that the planet could revolve at such speed that it would appear stationary. Smith went at once to the eastern window and watched closely, for fear some irregularity in that apparently perfect sphere might catch them unawares. They did not learn till later that Venus’s day is a little less than twenty-five hours, and therefore, since they had approached her near the equator, the wind they had encountered was moving at nearly nine hundred miles per hour!

Bit by bit, though, the cube answered to the wind-pressure. Soon they noted the sun rising slowly; and by the time it was two hours high the surface, which had been whizzing under them like some highly polished top, became entirely motionless: The cube had “stopped.”

One minute later the car touched the level. Smith very slowly reduced the repelling current so that the immense weight of the cube was but gradually shifted to

Comments (0)