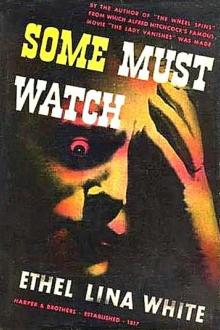

Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗

- Author: Ethel Lina White

- Performer: -

Book online «Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗». Author Ethel Lina White

rank growth of docks and nettles, to mark a tramp’s camping-place.

Again Helen thought of the murders.

“It’s coming nearer—and nearer. Nearer to us.”

Suddenly, she wondered if she were being followed. As she stopped to

listen, the hollow seemed to be murmurous with faint sounds—the whisper

of shrivelled leaves, the snapping of twigs, the chuckles of dripping

water.

It was possible to fancy anything. Although she knew that, if she ran,

her imagination would gallop away with her, she rushed across the soft

ground, collecting poultices of mud on the soles of her boots.

Her heart was pounding when the opposite lane reared itself in front of

her, like the wall of a house. The steepness however proved deceptive,

for, around the first bend, it doubled, like a crooked arm, to relieve

the steepness of the gradient.

Once more, Helen’s normal courage returned, for her watch told her that

she had won her race against time. The precious new job was safe. Her

legs ached as she toiled upwards, but she cheered herself by the

reminders that a merry heart goes all the way—that the longest lane has

a turning—that every step was bringing her nearer home.

Presently she reached the top of the rise, and entered the plantation,

which was thinly planted with young firs and larches, and carpeted with

fallen needles. At its thickest part, she could see through it, and,

suddenly, she caught sight of the Summit.

It was no longer a distant silhouette, but was so close that she could

distinguish the color of the window-curtains in the blue room. The

vegetable garden sloped down to the wall which bounded the plantation,

and a coil of rising smoke, together with a cheerful whistle told her

that the gardener was on the other side, making a bonfire.

At the sight of her goal, Helen slackened her pace. Now that it was

over, her escapade seemed an adventure, so that she felt reluctant to

return to dull routine. Very soon, she would be going round, locking up

in readiness for Curfew. It sounded dull, for she had forgotten that, in

the darkness of the hollow, she realized the significance of a barred

bedroom window.

The rising wind spattered her face with rain, and increased her sense of

rebellion against four walls and a roof. She told herself that it was

blowing up for a dirty night, as she walked towards the front gate.

At its end, the plantation thinned down to a single avenue of trees,

through which she could see the stone posts of the entrance to the

Summit, and the laurels of the drive. As she watched, fresh lights

glowed through the drawingroom windows.

It was the promise of tea—calling her home. She was on the point of

breaking into a run, when her heart gave a sudden leap.

She was positive that the furthest tree had moved.

She stopped and looked at it more closely, only to conclude that her

fancy had tricked her. It was lifeless and motionless, like the rest.

Yet there was something about its shape—some slight distortion of the

trunk—which filled her with vague distrust.

It was not a question of logic—she only knew that she did not want to

pass that special tree.

As she lingered, in hesitation, her early training asserted itself. She

began to earn her living, at the age of fourteen, by exercising the dogs

of the wealthy. As these rich dogs were better-fed, and stronger than

herself, they often tried to control a situation, so—she was used to

making quick decisions.

In this instance, her instinct dictated a short way home, which involved

a diagonal cut across boggy ground, through a patch of briars, and over

the garden wall.

She carried through her programme, in the minimum of time, and with

little material damage, but complete loss of dignity. After a safe, but

earthy, landing in the cabbage-bed, she walked around to the front door.

With her latch key in the lock, she turned, for a last look at the

plantation, visible through the gates.

She was just in time to see the last tree split into two, as a man

slipped from behind its trunk, and disappeared into the shadow.

THE FIRST CRACKS

The surge of Helen’s curiosity was stronger than any other emotion. It

compelled her to rush down the drive, in an effort to investigate the

mystery. But when she reached the gate she could see only lines of

trunks, criss-crossing in confusing perspectives.

Forgetful of her duties, she stood gazing into the gloom of the

plantation while a first star trembled through a rent in the tattered.

clouds.

“It was a man,” she thought triumphantly, “so I was right. He was

hiding.”

She knew that the incident admitted the simple explanation of a young

man waiting for his sweetheart. Yet she rejected it, partly because she

wanted a thrill, and partly because she did not believe it met the case.

In her opinion, a lover would naturally pass the time by pacing his

beat, or smoking a cigarette.

But the rigid pose, and the lengthy vigil, while the man stood in.

mimicry of a tree, suggested a tenacious purpose.

It reminded her of the concentrated patience of a crocodile, lurking in

the shadow of a river bank, to pounce on its prey.

“Well, whatever he was doing, I’m glad I didn’t pass him,” she decided

as she turned to go back to the house.

It was a tall grey stone building, of late Victorian architecture, and

it looked strangely out of keeping with the savage landscape. Built with

a flight of eleven stone steps leading up to the front door, and large

windows, protected with green jalousies, it was typical of the

residential quarter of a prosperous town. It should have been surrounded

by an acre of well-kept garden, and situated in a private road, with

lamp-posts and a pillar-box.

For all that, it offered a solidly resistant front to the solitude. Its

state of excellent repair was evidence that no money was spared to keep

it weather-proof. There was no blistered paint, no defective guttering.

The whole was somehow suggestive of a house which, at a pinch, could be

rendered secure as an armored car.

It glowed with electric-light, for Oates’ principal duty was to work the

generating plant. A single wire overhead was also a comfortable

reassurance of its link with civilization.

Helen no longer felt any wish to linger outside. The evening mists were

rising so that the evergreen shrubs, which clumped the lawn, appeared to

quiver into life. Viewed through a veil of vapor, they looked black and

grim, like mourners assisting at a funeral.

“If I don’t hurry, they’ll get between me and the house, and head me

off,” Helen told herself, still playing her favorite game of

make-believe. She had some excuse for her childishness, since her sole

relaxation had been a tramp through muddy blind lanes, instead of three

hours at the Pictures.

She ran eagerly up the steps, and, after a guilty glance at her shoes,

put in some vigorous foot-work on the huge iron scraper. Her latch-key

was still in the lock, where she had left it, before her swoop down the

drive. As she turned it, and heard the spring lock snap behind her,

shutting her inside, she was aware of a definite sense of shelter.

The house seemed a solid hive of comfort, honeycombed with golden

cells, each glowing with light and warmth. It buzzed with voices, it

offered company, and protection.

In spite of her appreciation, the interior of the Summit would have

appalled a modern decorator. The lobby was floored with black and ginger

tiles, on which lay a black fur rug. Its furniture consisted of a chair

with carved arms, a terra cotta drain-pipe, to hold umbrellas, and a

small palm on a stand of peacock-blue porcelain.

Pushing open the swing-doors, Helen entered the hall, which was entirely

carpeted with peacock-blue pile, and dark with massive mahogany. The

strains of wireless struggled through the heavy curtain which muffled

the drawingroom door, and the humid air was scented with potted

primulas, blended with orange-pekoe tea.

Although Helen’s movements had been discreet, someone with keen hearing

had heard the swing of the lobby doors. The velvet folds of the portiere

were pushed aside, and avoice cried out in petulant eagerness.

“Stephen, you. Oh, it’s you.”

Helen was swift to notice the drop in young Mrs. Warren’s voice.

“So you were listening for him, my dear,” she deduced. “And dressed up,

like a mannequin.”

Her glance of respect was reserved for the black-and-white satin

tea-frock, which gave the impression that Simone had been imported

straight from the London Restaurant the dansant, together with the

music. She also followed the conventions of fashion in such details as

artificial lips and eyebrows superimposed on the original structure. Her

glossy black hair was sleeked back into curls, resting on the nape of

her neck, and her nails were polished vermilion.

But in spite of long slanting lines, painted over shaven arches, and a

tiny bow of crimson constricting her natural mouth, she had not advanced

far from the cave. Her eyes glowed with primitive fire, and her

expression hinted at a passionate nature. She was either a beautiful

savage, or the last word in modern civilization, demanding

self-expression.

The result was, the same—a girl who would do exactly as she chose.

As she looked down, from her own superior height, at Helen’s small,

erect figure, the contrast between them was sharp. The girl was hatless,

and wore a shabby tweed coat, which was furred with moisture. She brought

back with her the outside elements, mud on her boots, the wind in her

cheeks, and glittering drops on her mop of ginger hair.

“Do you know where Mr. Rice is?” demanded Simone.

“He went out of the gate, just before me,” replied Helen, who was a born

opportunist, and always managed to be present at the important entrances

and exits. “And I heard him saying something about ‘wishing good-bye’.”

Simone’s face clouded at the reminder that the pupil was going home on

the morrow. She turned sharply, when her husband peered over her

shoulder, like an inquisitive bird. He was tall, with a jagged crest of

red hair, and horn-rimmed glasses.

“The tea’s growing stewed,” he said, in a high-pitched voice. “We’re not

going to wait any longer for Rice.”

“I am,” Simone totd him.

“But the tea-cake’s getting cold.”

“I adore cold muffin.”

“Well—won’t you pour out for me?” “Sorry, darling. One of the things my

mother never taught me.”

“I see.” Newton shrugged as he turned away. “I hope the noble Rice will

appreciate your sacrifice.”

Simone pretended not to hear, as she spoke to Helen, who had also

feigned deafness.

“When you see Mr. Rice, tell him we’re waiting tea for him.” I

Helen realized that the entertainment was over, or rather, that the

scene had been ruthlessly cut, just when she was looking forward to

reprisals from Simone.

She walked rather’ reluctantly upstairs, until she reached the first

landing, where she paused, to listen, outside the blue room. It always

challenged her curiosity, because of the formidable old invalid who lay

within, invisible, but paragraphed, like some legendary character.

As she could hear the murmur of Miss Warren’s voice—for the

stepdaughter was acting as deputy nurse—she decided to slip into her

room, to put it ready for the night.

The Summit was a three-storied house, with two staircases and a

semi-basement.

Comments (0)