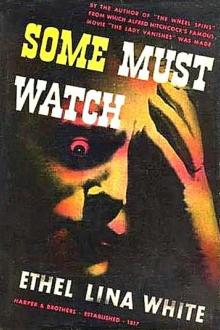

Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗

- Author: Ethel Lina White

- Performer: -

Book online «Some Must Watch, Ethel Lina White [crime books to read txt] 📗». Author Ethel Lina White

“Why?” asked Helen. “What is it?”

“The wine-cellar—and the Professor keeps the key. It’s the nearest

you’ll ever get to it.”

Helen, who was a total abstainer, through force of circumstances,

realized that, since she had been at the Summit, o intoxicant had been

served with the meals.

“Are they all teetotallers here?” she asked.

“There’s nothing to hinder the Professor having his glass,” said Mrs.

Oates, “seeing as he keeps the key. But Oates and the young gentlemen

have got to go to the Bull for their drop of tiddley. And Mr. Rice is

the only one as has ever asked me if I have a mouth.”

“What a shame not to allow you beer, with all your heavy work,”

sympathized Helen.

“I get beer-money,” admitted Mrs. Oates. “Miss Warren’s got a bee in her

bonnet about no drink served in the house. But she’s like the Professor,

no trouble so long as you leave her with her books. She’s not mean—only

you mustn’t do a thing what’s worth doing. That’s her.”

That was exactly how Miss Warren had struck Helen—a Grey studious

negation.

Mrs. Oates relieved her feelings by kicking the cellar door, before they

turned away.

“I’ve promised myself one thing,” she said solemnly. “It’s this, if ever

I come across the key of this cellar, there’ll be a bottle short.”

“And the fairies will have drunk it, I suppose?” asked Helen. “Come back

to the fire. I’ve something thrilling to tell you.”

When they were back in the kitchen, however, Mrs. Oates began to

chuckle.

“You’ve something to tell me. Well, I’ve something to show you. Look at

these.”

She opened one of the cupboards in the dresser, and pointed to a line of

empty bottles.

“What Mr. Rice calls ‘dead men.’ Many’s the bottle of gin or stout he’s

brought back from the Bull.”

“He’s kind,” admitted Helen. “There’s something aoout him. Pity he’s

such a rotter.”

“He’s not as black as he’s painted,” said Mrs. Oates.

“He was sent down from his school in Oxford for mucking about with a

girl. But he told me, one night, as he was more sinned against than

sinning. He’s not really partial to girls.”

“But he flirts with Mrs. Newton.”

“Just his fun. When she says ‘A,’ he says ‘B.’ That’s all.”

Helen laughed as she looked into the glowing heart of the fire. Unknown

to her, fresh cracks had been started in the walls of her fortress. As

she stroked the ginger cat, who responded with a startling rumble, her

recent experience seemed very remote.

“I promised you a tale,” she said. “Well—‘believe me or believe me not’

-when I was coming through the plantation, I met—the strangler.”

It was certain that she did not believe her own story, although she

exaggerated the details, in order to impress Mrs. Oates. It was such—a

thin-spun theme—a man hiding behind a tree, with no sequel to prove a

dark motive.

She was not the only one to be incredulous. In a cottage halfway up the

hillside, a dark-eyed girl was looking at herself in a, small mirror,

spotted with damp. Her face was rosy from moist mountain air, and her

expression was eager and rebellious.

Here was one who welcomed life with both hands. She perched a scarlet

hand-knitted beret at a perilous angle on her short black hair, powdered

her cheeks, and added unnecessary lipstick to her moist red lips,

humming, as an accompaniment to her actions.

As she looked around the small room, with the low bulging white plaster

ceiling and cracked walls, ‘the limp muslin curtain before the shuttered

window, her desire grew.. She told herself that she was sick of

confinement and the cheesy smell of indoors. She had stayed in, night

after night, until she was fed up, and willing to chance any

hypothetical criminal. She yearned for the cheery bar of the Bull, with

a young man or two, a glass of cider, and the magic of the Wireless.

She buttoned up her red leather coat and put on Wellington boots, before

her stealthy descent down the creaking stairs. When she slipped through

the cottage door her heart beat faster, but only with excitement. She

was as used to the narrow, pitchy lane, which dropped down precipitously

to the valley, as a Londoner is to Piccadilly. Familiarity with

loneliness had robbed it of any terror, just as immunity from attack had

resulted in perfect nerve. Without fear or foreboding, she hurried down

the stony hillside, in sure-footed haste.

When she reached the plantation, she felt that she had nearly reached

the goal of her desire. A bare mile of level ground separated her from

the bar of the Bull. Civilization was represented by the Summit, which

was so close to her that she could hear a broadcast of Jack Hylton’s

band.

Like most Welsh girls, she had a true ear and a musical voice. She took

up the tune, jumbling the words, but singing with the passionate

exaltation due to a revivalist hymn.

“Love is the sweetest thing.

No bird upon the wing”

The rain drove down upon her face, in steady slanting skeins, through

the partial screen, of the larches, and the hard ground under her feet,

was growing slimed, in spite of its carpet of spines. Happy, healthy,

and unwise, she hurried to meet the future. Careless of weather, and one

with the elements, she sang her way through the wood—youth at its peak.

Her sight was excellent, so that she could distinguish the lane of

single trees, where the plantation thinned towards its end. But her

imagination was more blunted than Helen’s, so that she did notice that

one Of the trees was apparently rootless, for it shifted behind the

trunks of its fellows.

Had she remarked it, she would have distrusted the evi dence of her

eyes. Common sense told her that trees did not move from their stations.

So she hurried on, and sang yet louder.

“I only pray that life may bring Love’s sweet story to you.”

When she reached the last tree, it suddenly changed intoa man. Its

branches were clutching arms… But still she did not believe.

For she knew that these things do not happen.

ANCIENT LIGHTS

The tree moved,” declared Helen, finishing her story, in the safety of

the kitchen. “And—to my horror—I saw that it was a man. He was waiting

there, like a tiger ready to spring on his prey.”

“Go on.” Mrs. Oates was openly derisive. “I’ve seen that tree, myself.

Often seen him, I have, waiting for Ceridwen, when she used to work

here. And was never the same tree twice.”

“Cerwiden?” repeated Helen.

“Yes. She lives in a cottage halfway up the hill. A pretty girl, but

she would mix her cloths. Old Lady Warren couldn’t abide her. She said

as how her feet smelt, and when she dusted under her bed, her ladyship

used to wait for her, with her stick, until she crawled out, so as to

fetch her a clout on the head.”

Helen burst out laughing. Life might ignore her, but she remained

acutely conscious and appreciative of the eternal comedy.

“The old darling gets better and better,” she declared. “I wish you’d

give me the job of dusting under her bed. She’d find me a bit too quick

for her.”

“So was Cerwiden. She used to bait the old girl shooting out when she

wasn’t expecting her… But she got her, in the end. She fetched her

such a crack that her father came and took her away.”

“She certainly makes—What’s that?”

Helen broke off to listen. Once again the sound was repeated—an

insistent tapping on a window-pane. Although she could not locate it, it

seemed to be not far away.

“Is someone knocking?” she asked.

Mrs. Oates listened also.

“It must be the passage window,” Mrs. Oates said. “The catch’ is loose.

Oates did talk of mending it.”

“That doesn’t sound too safe,” objected Helen.

“Now, miss, don’t worry. The shutter’s put up. No on can get in.”

But, as the wind rose, the monotonous rattle and beat continued, at

irregular intervals. It got on Helen’s nerves, so that she could not

settle down to her tea.

“It’s a miserable night,” she said.’ “If that tree was waiting for

Cerwiden, I don’t envy her.”

“He’s caught her by now,” chuckled Mrs. Oates. “She won’t be noticing

weather no more.”.

“There it goes a again… Have you a screwdriver?”

Helen’s eyes lit up as she spoke, for she had a mania for small

mechanical jobs.

“You see, Mrs. Oates, this sound will irritate you,” she explained. “And

then you’ll spoil the dinner. And then we shall have indigestion. I’ll

see if I can’t put it right.”

“What a one you are to look for work,” grumbled Mrs. Oates, as she

followed Helen through the scullery.

The smallish window was at the end of the passage, close to the scullery

door. As Helen unbarred the shutter, a gust of wind struck it, like a

blow, and dashed drops of rain against the streaming glass.

Together, the big woman and the small girl, stood, peering out into

the garden. They could see only a black huddle of shrubs and a gleam of

thrashing boughs.

“Doesn’t it look creepy?” said Helen. “I wonder if I can fix this catch.

Have you any small nails?”

“I’ll see if I can find some. Oates is a terror for nails.”

Mrs. Oates lumbered through the scullery, leaving Helen alone staring

out into the wet garden. There were no bushes, on this side, to give the

impression of a crawling greyness creeping towards the house; the night

seemed to have become solid and definite—clear-cut chunks of

threatening blackness.

It inspired a spirit of defiance in Helen.

“Come on—if you dare,” she cried aloud.

The answer to her challenge was immediate—a piercing scream from the

kitchen.

Helen’s heart leaped at the thin terror-stricken wail. There was only

room for one thought in her mind. The maniac was lurking in hiding, and

she had sent the poor unsuspecting Mrs. Oates into his trap.

“He’s got her,” she thought, as she caught up the bar and dashed into

the kitchen.

Mrs. Oates greeted her with another scream, but there was no sign of the

source of her terror, although she was on the verge of hysteria.

“A mouse,” she yelled. “It went over there.”

Helen stared at her in blank incredulity.

“You can’t be frightened of a little mouse. It isn’t done. Old stuff,

you know.” “But they make me crawl all over,” whimpered Mrs. Oates.

“In that case, I suppose murder will have to be com mitted. A pity.

Here, Ginger, Ginger.”.

Helen called, in vain, to the cat, who continued to wash with an

affectation of complete detachment. Mrs. Oates apologized for him. “He’s

a civil cat, but he can’t abide mice. Oates would swat it.”

“If that’s a hint, I’m not going to swat it. But I’ll frighten it away.”

With her sensitized reaction to any situation, she was conscious of

anti-climax, when she went down on her knees and began to beat the floor

with her bar. Just whenever the drama seemed to be working up to a

moment of tension, the crisis always eluded her and degenerated into

farce.

Not until the night was over could she trace the repercussions of each

trivial incident and realize that the wave of fear which flooded the

house,

Comments (0)