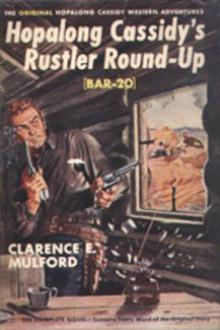

The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Book online «The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗». Author Clarence E. Mulford

Ackerman shook his head savagely. “With them six cows, an’ Logan missin’ hundreds?” he sarcastically demanded.

Quigley smiled patronizingly. “Findin’ only a few won’t mean nothin’, except that he’s driven off th’ rest every time he has got a few together, an’ sold ‘em. Now if you was to take that notebook that’s stickto’ out of yore pocket, an’ write in it some words an’ figgers showin’ that he’s sold so many cows, an’ what he got for ‘em each time, it might help. We’ll know when Logan’s due, an’ we can drop that book where he’ll find it. You never want to kill anythin’ till yo’re shore it ain’t goin’ to be useful. There’s one thing I’m set on: there ain’t going to be no unnecessary killin’.”

Ackerman laughed grimly. “Well, anyhow; I’ve started things. I left a note on his door tellin’ him what to do.”

“What did you write?” demanded Quigley.

Ackerman told him defiantly. “An’ what’s more,” he added, “I’m goin’ to do some pot-shootin’ before long.”

“Well,” replied Quigley, “I’d rather drive him out, an’ then watch him for a while. I ain’t shore he can’t be scared. Do you think he suspects he’s bein’ watched?”

“I don’t think so,” answered Fleming.

“I know he does!” snapped Ackerman. “Why does he paw around that gravel bed an’ pertend that he’s found gold in it? There ain’t no gold there!”

Quigley laughed. “He found gold, all right. Charley James saw it: an’ he got it right there. He wanted Charley to take it in pay. I don’t doubt that you know somethin’ about prospectin’ but ‘gold is where it’s found.’”

Ackerman thrust his head forward. “Gold in that gravel! H—l!”

“Charley saw it,” grunted Quigley.

“Charley be d dl” snorted Ackerman. He looked closely at Quigley and suddenly demanded: “What makes you so set ag’in us shootin’ him?”

Quigley regarded him evenly. “There was a lot of talk, when Porter was found dead. I told you all at th’ time. Four men have got curious, come up in these hills an’ never went out again. Twin Buttes has a bad name; an’ th’ next dead man that’s blamed on us is goin’ to make a lot more talk an’ may stir up trouble.

“Now then: Pop knows that Nelson’s up here, an’ that means that everybody knows it. He saw me reach for my gun, an’ heard me tell him to keep out of here. An’ let me tell you Pop knows more about us than he lets on; an’ he’s as venomous as a snake when he gets riled. An’ he ain’t th’ only one that knows things.

“Now we’ll add it up: If we can scare Nelson away, or discourage him, he’ll quit of his own accord; an’ he won’t talk because he knows that somebody knows he’s been rustlin’.” He turned on his heel. “Am I plain enough?”

“Wait a minute,” called Ackerman. “That feller has got me worried. Mebby it would be reckless to let him disappear up here; but suppose I go on a spree in town when he’s there? It’s easy to start a fight with a gun-man, because he’s got to toe th’ mark. I can do th’ job open an’ above board, an’ make it natural; an’ that will keep us clear.”

“Jim,” smiled Quigley, “I don’t want to lose you; an’ if you pick a square fight with that man, th’ eve? break that you demand in yore personal quarrels, wfc will lose you. I looked down his gun, an’ I tell you that I didn’t ‘ee him move. He’s a gun man! “

Ackerman laughed. “We won’t say anythin’ about that. But if he did get th’ worst of it in an even break an’ a personal quarrel, would it hurt us up here? That’s all I want to know.”

Quigley thought deeply and made a slow and careful reply. “If it wasn’t bungled I don’t see how it could. You’d have to rile him subtle, make him declare war an’ be th’ injured party yoreself; an’ you’d want witnesses. But don’t you do it, Jim; not nohow. I got a feelin’ that he’s th’ best man with a Colt in this section. Yo’re a wizard with a six-gun; but you ain’t good enough for him. When he’s around yo’re in th’ little boy’s class; an’ I ain’t meanin’ no offense to you, neither.”

Ackerman, hands on hips, stared at Quigley’s back as he walked away. “Th’ h—l you say!” he snorted wrathfully. ”’ Little boy’s class,’ huh?” He wheeled and turned a scowling face to his friend Fleming. “Did you hear that? I calls that rubbin’ it in! I got a notion to take that feller’s two guns away fronf him an’ make Tom eat ‘em! D d if I don’t, too; You ride to town with me an’ I’ll show you somethirf you won’t never forget!”

It may not be out of place here to say that the time soon came when he did show Fleming something; and that Fleming never did forget it.

Mr. Quigley smiled grimly as he entered the house, for it was his opinion that Mr. Ackerman had no peer in his use and abuse of Mr. Colt’s most famous invention. He hardly could ask Mr. Ackerman to sally forth and engage in a personal duel with a common enemy, for it would smack too much of asking a friend to do his fighting for him. He believed that leadership is best based when it rests upon the respect of those led. He had no doubt about the outcome of such a duel, for he implicitly believed that the stranger, despite his vaunting two guns, had as much chance against Mr. Ackerman’s sleight-of-hand as an enraged rattler had against a cool and businesslike king snake. The appropriateness of the simile made him smile, because the rattler is heavily armed and calls attention to the fact, while the king snake is modest, unassuming, and sounds no war-cry. Two guns meant nothing to Mr. Quigley, because he knew that one was entirely sufficient in the hand of the right man.

He had carefully pointed out the way for Mr. Ackerman to proceed in such a situation, and then warned him in an irritating way not to go ahead. So now he sighed with relief at a problem solved, for his knowledge of Mr. Ackerman’s character was based upon accurate observations extending over a long period of time.

JOHNNY got up at noon, and when he saw the sign on his door its single word “Vamose “told him that the valley and the cabin were of no further use to him; that the time for subterfuge and acting a part was past. That the rustlers were not certain of his intentions was plain, for otherwise there would have been a bullet instead of a warning; and he was mildly surprised that they had not ambushed him to be on the safe side.

It now remained for him to open the war, and warn them further; or to pretend to obey the mandate and seek new fields of observation. Pride and anger urged the former; common sense and craftiness, the latter; and since he had not accomplished his task he decided to swallow his anger and move. Had he been only what he pretended to be, Nelson’s creek would have seen some stirring times. As a sop to his pride he printed a notice on a piece of Charley’s wrapping paper and fastened it on the door. Its three, short words made a concise, blunt direction as to a certain journey, popularly supposed to be the more heavily traveled trail through the spirit world. Packing part of his belongings on Pepper, he found room to sit in the saddle, and started off for an afternoon in Hastings, after which he would return to the cabin to spend the night and to get the rest of his effects.

When he rode into town he laughed outright at the sign on Pop’s door, and he laughed harder when he saw another on Charley’s door; and leaving his things behind Pop’s saloon, he pushed on to Devil’s Gap. At the ford he met the two happy anglers returning and they paused in mid-stream to hold up their catch.

“You come back with us,” grinned Pop. “We’ll pool th’ fish an’ have a three-corner meal. Where was you goin’?”

“To find you,” chuckled Johnny. “I’m surprised at th’ way you both neglects business.”

“Comin’ from you that makes me laugh,” snorted Pop.

Charley grinned. “Did you see that whoppin’ big feller I got? Bet it’ll go three pounds.”

“Lucky if it’s half that,” grunted Pop. “If I’d ‘a’ got that one I had hold of, we’d’ve had a threepounder, or mebby a fourpounder.”

Charley snorted. “Who ever heard of a fourpound brook trout? Been a brown, now, it might ‘a’ been that big.”

“Why, I caught ‘em up to eight pounds, back East, when I was a kid!” retorted Pop.

“Yo’re a squaw’s dog liar!” snapped Charley. “Eight-pound brook trout! You must ‘a’ snagged a turtle, or an old boot full of mud!”

“Bet you five dollars!” retorted Pop, bristling.

“How you goin’ to prove it?” jeered Charley. “Call th’ dead back to life to lie for you?”

“Reckon I can’t prove it,” regretted Pop. “But when a man hangs around with a liar he shore gets th’ name, too.”

“Nobody never called me a liar an’ got off without a hidin’!” snapped Charley. “I may be sixty years old, but I can lick you an’ yore whole fambly if you gets too smart!”

Pop drew rein, his chin whiskers bobbing up and down. “I’m older’n that myself; but I don’t need no relations to help me lick you! Get off that hoss, if you dares!”

“Here! Here!” interposed Johnny. “What’s th’ use of you two old friends mussin’ each other up? Come on! I’m in a hurry! I’m hungry!”

“I won’t go a step till he says I ain’t no liar!” snapped Charley.

“I won’t go till he says I caught a eight-pound brook trout!”

“Mebby he did how do I know what he did when he was a boy?” growled Charley, full of fight. “But I ain’t no liar, an’ that’s that!”

“Who said you was, you old fool?” asked Pop heatedly.

“You did!”

“I didn’t!”

“You did!”

“Yo’re a liar!”

“Yo’re another!”

“Get off that hoss!”

“You ain’t off yore own yet!”

Johnny was holding his sides and Pop wheeled on him savagely. “What th’ h—l you laughin’ at?”

“That’s what I want to know!” blazed Charley.

“Come on, Charley!” shouted Pop. “We’ll eat them fish ourselves. It’s a fine how-dy-do when age ain’t respected no more. An’ th’ next time you goes around callin’ folks liars,” he said, shaking a trembling fist under Johnny’s nose, “you needn’t foller us to do it on!”

Down the trail they rode, angrily discussing Johnny, the times, and the manners of the younger generation.

When Johnny arrived at the saloon and tried the door he found it locked. He could hear footsteps inside and he stepped back, chuckling, to wait until Pop had forgiven him; but after a few minutes he gave it up and went around to try the window of a side room.

“What

Comments (0)