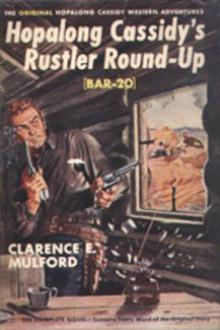

The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Book online «The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗». Author Clarence E. Mulford

The Man From Bar-20

A Story of the Cow-Country

BY CLARENCE E. MULFORD

Author of “Bar-20” “Hopalong Cassidy” “Buck Peters, Ranchman,” etc.

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Publishers

By arrangement with A. C. McClurg & Co.

CONTENTS

I A Stranger Comes to Hastings

II A Question of Identity

III The Wisdom of the Frogs

IV A Feint

V Preparations

VI A Moonlight Reconnaissance

VII A Council of War

VIII Fleming Is Shown

IX A Skirmish in the Night

X A Change of Base

XI Nocturnal Activities

XII Yeasty Suspicion

XIII An Observant Observer

XIV The End of a Trail

XV Blindman’s Buff

XVI The Science of Sombreros

XVII Treed

XVIII At Bay

XIX An Unwelcome Visitor

XX A Past Master Draws Cards

XXI Scouting as a Fine Art

XXII “Two Ijuts”

XXIII “All but th’ Cows”

The Man From Bar-20

A HORSEMAN rode slowly out of a draw and up a steep, lava-covered ridge, singing “The Cowboy’s Lament,” to the disgust of his horse, which suddenly arched its back and stopped the song in the twenty-ninth verse.

“Dearly Beloved,” grinned the rider, after he had quelled the trouble, “yore protest is heeded ‘Th’ Lament’ ceases, instanter; an’ while you crop some of that grass, I’ll look around and observe th’ scenery, which shore is scrambled. Now, them two buttes over there,” leaning forward to look around a clump of brush, “if they ain’t twins, I’ll eat —”

He ducked and dismounted in one swift movement to the vengeful tune of a screaming bullet over his head, slapped the horse and jerked his rifle from its scabbard. As the horse leaped down the slope of the ridge there was no sign of any living thing to be seen on the trail. A bush rustled near the edge of a draw, a peeved voice softly cursed the cacti and Mexican locust; and a few minutes later the shadow of a black lava bowlder grew suddenly fatter on one side. The cause of this sudden shadow growth lay prone under the bulging side of the great rock, peering out intently between two large stones; and flaming curiosity consumed his soul. A stranger in a strange land, who rode innocently along a free trail and minded his own business, merited no such a welcome as this. His promptness of action and the blind luck in that bending forward at the right instant were all that saved his life; and his celerity of movement spoke well for his reflexes, for he had found himself fattening the shadow of the bowlder almost before he had fully realized the pressing need for it.

Minute after minute passed before his searching eyes detected anything concerned with the unpleasant episode, and then he sensed rather than saw a slight movement on the mottled, bowlder-strewn slope of a distant butte. A bush moved gently, and that was all.

To cross the intervening chaos of rocks and brush, pastures and draws would take him an hour if it were done as caution dictated, and by that time the chase would be useless. So he waited until the sun was two hours higher, pleasantly anticipating a stealthy reconnaissance by his unknown enemy to observe the dead. He had dropped into high grass and brush when he left the saddle and there was no way that the marksman could be certain of the results of his shot except by closer examination. But the man in ambush had no curiosity, to his target’s regret; and the target, despairing of being honored by a visit, finally gave up the vigil. After a silent interval a soft whistle from a thicket, well back in a draw, caused the grazing horse to lift his head, throw its ears forward and walk sedately toward the sound.

“Dearly Beloved,” said a low voice from the thicket, “come closer. That was a two-laigged skunk, an’ his eyes are good. Likewise he is one plumb fine shot.”

Ever since he had listened to the marriage ceremony which had subjugated his friend Hopalong for the rest of that man’s natural life, the phrase “Dearly Beloved” had stuck in his memory; and in his use of it the words took the place of humorous profanity.

Mounting, he rode on again, but kept off all skylines, favored the rough going away from the trail, and passed to the eastward of all the obstructions he met; and his keen eyes darted from point to point unceasingly, not giving up their scrutiny of the surroundings until he saw in the distance a little town, which he knew was Hastings.

In the little cow-town of Hastings the afternoon sun drove the shadows of the few buildings farther afield and pitilessly searched out every defect in the cheap and hastily constructed frame buildings, showed the hair-line cracks in the few adobes, where an occasional frost worked insidious damage to the clay, and drew out sticky, pungent beads of rosin from the sunbleached and checked pine boards of the two-story front of the one-story building owned and occupied by “Pop” Hayes, proprietor of one of the three saloons in the town. The two-story front of Pop’s building displayed two windows painted on the warped boards too close to the upper edge, the panes a faded blue, where gummy pine knots had not stained them yellow; and they were framed by sashes of a hideous red.

Inside the building Pop dozed in his favorite position, his feet crossed on a shaky pine table and his chair tipped back against the wall. Slow hoofbeats, muffled by the sand, sounded outside, followed by the sudden, faint jingling of spurs, the sharp creak of saddle gear and the soft thud of feet on the ground. Pop’s eyes opened and he blinked at the bright rectangle of sunny street framed by his doorway, where a man loomed up blackly, and slowly entered the room.

“Howd’y, Logan,” grunted Pop, sighing. His feet scraped from the table and thumped solidly on the floor in time with the thud of the chair legs, and he slowly arose, yawning and sighing wearily while he waited to see which side of the room would be favored by the newcomer. Pop disliked being disturbed, for by nature he was one who craved rest, and he could only sleep all night and most of the day. Rubbing the sleep out of his eyes he yawned again and looked more closely at the stranger, a quick look of surprise flashing across his face. Blinking rapidly he looked again and muttered something to himself.

The newcomer turned his back to the bar, took two long steps and peered into the battered showcase on the other side of the room, where a miscellaneous collection of merchandise, fly-specked and dusty, lay piled up in cheerful disorder under the cracked and grimy glass. Staring up at him was a roughly scrawled warning, in faded ink on yellowed paper: “Lean on yourself.” The collection showed Mexican holsters, army holsters, holsters with the Lone Star; straps, buckles, bone rings, star-headed tacks, spurs, buttons, needles, thread, knives; two heavy Colt’s revolvers, piles of cartridges in boxes, a pair of mother-of-pearl butt plates showing the head of a long-horned steer; pipes, tobacco of both kinds, dice, playing cards, harmonicas, cigars so dried out that they threatened to crumble at a touch; a patented gun-sight with Wild Bill Hickok’s picture on the card which held it; oil, corkscrews, loose shot and bullets; empty shells, primers, reloading tools; bar lead, bullet molds all crowded together as they had been left after many pawwigs-over. Pop was wont to fretfully damn the case and demand, peevishly, to know why “it” was always the very last thing he could find. Often, upon these occasions, he threatened to “get at it” the very first chance that he had; but his threats were harmless.

The stranger tapped on the glass. “Gimme that box of .45‘8,” he remarked, pointing. “No, no; not that one. This new box. I’m shore particular about little things like that.”

Pop reluctantly obeyed. “Why, just th’ other day I found a box of cartridges I had for eleven years; an’ they was better’n them that they sells nowadays. That’s one thing that don’t spoil.” He looked up with shrewdly appraising eyes. “At fust glance I thought you was Logan. You shore looks a heap like him: dead image,” he said.

“Yes? Dead image?” responded the stranger, his voice betraying nothing more than a polite, idle curiosity; but his mind flashed back to the trail. “Hum. He must have a lot of friends if he looks like me,” he smiled quizzically.

Pop grinned: “Well, he’s got some as is; an’ some as ain’t,” he replied knowingly. “An’ lemme tell you they both runs true to form. You don’t have to copper no bets on either bunch, not a-tall.”

“Sheriff, or marshal?” inquired the stranger, turning to the bar. “It’s plenty hot an’ dusty,” he averred, “You have a life-saver with me.”

“Might as well, I reckon,” said Pop, shuffling across the room with a sudden show of animation, “though my life ain’t exactly in danger. Nope; he ain’t no sheriff, or marshal. We ain’t got none, ‘though I ain’t sayin’ we couldn’t keep one tolerable busy while he lived. I’ve thought some of gettin’ th’ boys together to elect me sheriff; an’ cussed if I wouldn’t ‘a’ done it, too, if it wasn’t for th’ ridin’.”

“Ridin’?” inquired the stranger with polite interest.

“It shakes a man up so; an’ I allus feels sorry for th’ hoss,” explained the proprietor.

The stranger’s facial training at the great American game was all that saved him from committing a breach of etiquette. “Huh! Reckon it does shake a man up,” he admitted. “An’ I never thought about th’ cayuse; no, sir; not till this minute. Any ranches in this country?”

“Shore; lots of ‘em. You lookin’ for work?”

“Yes; I reckon so,” answered the stranger.

“Well, if you don’t look out sharp you’ll shore find some.”

“A man’s got to eat more or less regular; an’ cowpunchers ain’t no exception,” replied the stranger, his soft drawl in keeping with his slow, graceful movements.

Pop, shrewd reader of men that he was, suspected that neither of those characteristics was a true index to the man’s real nature. There was an indefinable something which belied the smile—the eyes, perhaps, steel blue, unwavering, inscrutable; or a latent incisiveness crouching just beyond reach; and there was a sureness and smoothness and minimum of effort in the movements which vaguely reminded Pop of a mountain lion he once had trailed and killed. He was in the presence of a dynamic personality which baffled and disturbed him; and the two plain, heavy Colt’s resting in open-top holsters, well down on the stranger’s thighs, where his swinging hands brushed the wellworn butts, were signs which even the most stupid frontiersman could hardly overlook. Significant, too, was the fact that the holsters were securely tied by rawhide thongs, at their lower ends, to the leather chaps, this to hold them down when the guns were drawn out. To the initiated the signs proclaimed a gunman, a two-gun man, which was worse; and a red flag would have had no more meaning.

“Well,” drawled Pop, smiling amiably, “as to work, I reckon you can find it if you knows it when you sees it; an’ don’t close yore eyes. I’ll deal ‘em face up, an’ you

Comments (0)