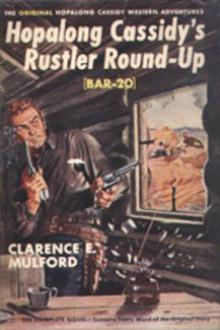

The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Book online «The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗». Author Clarence E. Mulford

Having located the valley, he slipped away, mounted his horse and rode back the way he had come, looking for a good place to pitch his camp. Five miles from the valley he found it a cave-like recess under the towering wall of a butte, half way up the wooded slope which lay at the foot of the wall. From it he could command all approaches for several hundred yards, while his tarpaulin would be screened by bowlders and trees. It was high enough for purposes of observation, but not so high that the smoke from his fire would have density enough when it reached the top of the butte to be seen for any distance. A spring close by formed pools in the hollows of the rocks below him. The greaC buttes lying to the east of the fire would screen its light from any wandering member of Quigley’a outfit

This is it,” he grunted “We’ll locate here tomorrow.”

The following day, having put his new camp to rights, he rode up the western slope of the great plateau which hemmed in Quigley’s ranch, picketed his horse in a clearing, and after a cautious reconnaissance on foot he reached the edge of the cliffs, and the valley lay before him. Cattle grazed near a little lake, but at that distance he could not read the brands. He first had to find out if any of the outfit ever rode along the top of the cliffs, and he struck straight back to cross any such trails. By evening he had covered the western side of the ranch without finding a hoof-print, or a way up the sheer walls where a horseman could reach the top. There were several places where a coolheaded man could climb up, and at one of these Johnny found several burned matches.

The next day was spent on the plateau north of the ranch, and the third and fourth days found him examining the eastern side; and it was here that he found signs of riders. There were three blind canyons on this side, and the middle one had a good trail running up its northern wall, and it appeared to be used frequently. At the top it divided, one branch running north and the other south. It was the only place on that side of the valley where a horseman could get out.

Now that he had become familiar with his surroundings he began his real work. If Quigley had rustled, the operations could be divided into two classes: past operations, now finished; or present operations which were to continue. It was possible that enough cattle had been stolen in the past so that the natural increase would satisfy a man of modest ambitions. In this case his danger would decrease as time passed and eventually he would have a well-stocked range and be above suspicion. If he were avaricious the rustling would continue, if only spasmodically, until he had made all the money he wanted or until his operations became known.

Johnny early had discovered that Quigley’s brand was QE and this increased his suspicions, for the E could not be explained. Logan’s brand was childishly simple to change: The C could become an O, Q, G, or wagon-wheel; the L would make an E, Triangle, Square, or a 4.

Satisfied that the foundation of Quigley’s brand had been the CL, Johnny had to discover if Logan’s cattle still were being taken to swell the Quigley herds. Logan’s inaction and his easy-going way of running his ranch jarred Johnny, for the foreman had confessed that for the last few years the natural increase, figured in the fall roundups, had not tallied with the number of calves branded each preceding spring. But Logan was not altogether to blame, because the Barrier had given him a false security and there was nothing to fear from other directions. It was the last spring roundup and its tally sheets which had stirred him; and a close study of his drive-herd records and the use of , factor of natural increase suddenly brought to his mind a startling suspicion. Even then he wavered, fearing that he was allowing an old and bitter grudge to sway him unduly; and before he had time to make any real investigations, Johnny had appeared and demanded a job.

Among Quigley’s cattle the proportion of calves to cows was so small that Johnny could not fail to notice it. He was satisfied that the QE, so prominently displayed, originally had been CL, but when he caught sight of a crusty old steer near the mouth of the second canyon all doubts were removed. While the mark was an old one, the rebranding had been done carelessly. The segment which closed the original C had not been properly joined to the old brand, and there was a space between the ends of the two marks where they overlapped. A look at the ears made him smile grimly, for Logan’s shallow’ve notch had become a rounded scallop; and there was no honest reason why Quigley should notch the ears of his cows when there was no chance of them getting mixed up with the cattle of any other ranch, The scallop had been made simply to cut out the tell tale’ve notch.

LIGHT gleamed from Quigley’s ranchhouses and an occasional squeal came from the corral, suggesting that “Big Jake” was getting up steam for more deviltry. Occasionally a shadow passed across the lighted patches of ground below the windows and the low song of Rustler Creek could be heard as it swirled into the long, black canyon. Save for the glow of the windows and the rectangles of light below them everything was wrapped in darkness, and the canyon, the range, and the rims of the cliffs were hidden.

“A miner, ‘forty-niner, and his daughter, Clementine’ 9 came from the middle house as Art Fleming dolefully made known the sorrowful details of Clementine’s passing out. He put his heart into it because he had troubles of his own, for which he frankly and profanely gave Ben Gates due discredit.

Ben, tiring of the dirge, heaved a boot with a snapshooter’s judgment and instantly forsook the heavy inhospitality of the house for the peace and freedom of the great outdoors. He plumped down on a bench and immediately arose therefrom.

“Look where yo’re settin’, you blunderin’ jackass!” snarled a hostile voice from the same bench. “Yo’re as big a nuisance as a frisky bummer in a night herd!”

“A bull’s eye for Mr. Harrison,” I chanted the man inside.

“You two buzzards are about as cheerful an’ pleasant as a rattler in August,” snapped Gates belligerently. “Like two old wimmin, you are, both of you! Settin’ around in everybody’s way, tellin I yore troubles over an j over again till everybody wishes Nelson had done a better job. How’d I know you was sprawled out, takin’ up all th’ room? You reminds me of a fool dog that sets around stickin’ its tail in everybody’s way, an’ then howls blue murder when it’s stepped on. Think yo’re th’ only people on this ranch that has any troubles?”

“A miss for Mr. Gates,” said the irritated voice within the house. “An’ if he will stick his infected head in that door, just for one, two, three, he’ll have more troubles,” prophesied Mr. Fleming, facing the opening with a boot nicely balanced in his upraised hand. “If it wasn’t for him, we—”

“Shut up! Shut up!” yelled Gates, enraged in an instant. “If you says that much more I’ll bust yore fool neck! For G-d’s sake, is that all you know, Andrew Jackson?”

“If it wasn’t for you,” said the man on the bench Very deliberately as his hand closed over a piece of firewood, “I said, if it wasn’t for you, we’d be ridin’ with the boys tonight, instead of stayin’ around these houses like three sick babies.”

“Another bull’s eye for Mr. Harrison,” said the man inside.

Gates wheeled with an oath. “An’ if it wasn’t for you sound asleep in th’ valley; an’ Fleming sound asleep up on that butte, I wouldn’t ‘a’ been lammed on th’ head an’ tied up like a sack! It’s purty cussed tough when a man with nothin’ worse than a scalp wound has to lay up this way!”

“Bull’s eye for Mr. Gates,” announced the man in the cabin, with great relish.

“If you’d been wide awake yoreself,” retorted Harrison, “you wouldn’t ‘a’ been tied >sp! You didn’t even squawk when he hit you, so we’d know he was around. Was you tryin’ to keep it a secret?” he demanded with withering sarcasm. “An’ as for them bandages, how did I know th’ dog had been sleepin’ on ‘em? Cookie gave ‘em to me!”

“Bull’s eye for Mr. Harrison,” said Fleming. “But he was awake,” he continued with vast conviction. “He wat wide awake. He ain’t got no more sense awake than he has asleep. When he’s got his boots on, his brains are cramped an’ suffocated.”

“You got him figgered wrong,” said Harrison “His brains are only suffocated when he sets down.”

While the little comedy was being enacted at the bunk-houses, the main body of rustlers followed Quigley down the steeply sloping bottom of a concealed crevice miles north of the ranchhouse of the CL. The five men emerged quietly and paused on the edge of the curving Deepwater, and then slowly followed their leader into the icy stream. The current, weakened by a widening of the river at this point, still flowed with sufficient strength to make itself felt and the slowly moving horses leaned against it as they filed across the secret ford. Reaching the farther bank the second and third men rode quietly to right and left, rapidly becoming vague and then lost to sight. The three remaining riders sat quietly in their saddles for what, to them, seemed to be a long time. Suddenly a low whistle sounded on the left, followed instantly by another on the right; and like released springs the rustlers leaped into action.

Vague, ghostly figures moved over the open plain, finding cows with uncanny directness and certainty. Two riders held the nucleus of the little herd, which grew steadily as lumbering cows, followed inexorably by skilled riders, pushed out of the darkness. There was no conversation, no whistling now, nor singing, but a silence which, coupled to the ghost-like action and the dexterous swiftness, made the drama seem unreal.

There came an abrupt change. The two men riding herd saw no more looming cattle or riders, which seemed to be a matter of significance to them, for they faced southward, guns in hand, and pushed slowly back along the flanks of the little herd. Peering into the shrouding gray darkness, tense and alert, eyes and ears straining to read the riddle, they waited like sooty statues for whtt<’^er might occur, rigid and unmoving.

A sudden thickening in the night. A figure seemed to flow from indefinable density to the outlines of a mounted man. A low voice, profanely irritant, spoke reassuringly and grew silent as the rider oozed back into the effacing night.

“Shore,” muttered a herder, relaxing and slipping his gun into its holster. He moved forward swiftly and turned back a venturesome cow. His companion, growling but relieved,

Comments (0)