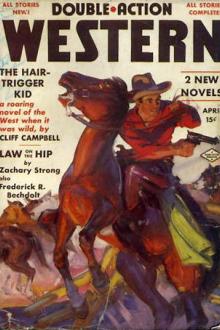

The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗». Author Max Brand

“Yes, because I’m straight.”

He blinked a little, as though he had seen a sudden light. Then he said:

“Suppose that I tell you the story of the four men? Will you let me off

with that chapter?”

“What am Ito offer in exchange?”

“Nothing,” said the Kid. “I’ve seen your story, and I don’t need to hear

it.”

She blushed in her turn, but without lowering her eyes.

“The first man,” said the Kid, striking at once into the middle of his

story, “was a fellow named Turk Reming. He was a darkish man, with a

mustache that he twisted so much that it curled forward instead of back.

He had three wrinkles between his eyes, and he always seemed to be

smiling like a devil. I found the Turk doing business as the chief boss,

gunman, and professional bully of a big mining camp—a new strike up in

Montana—”

“How old were you?” asked the girl.

“Well, the age doesn’t matter,” said he.

“You were fifteen,” she insisted.

“I suppose I was.”

He seemed irritated by this.

“I took my time with Turk. I wanted to take my time with all of ‘em. My

mother had died by slow torture. My father had died after forgetting how

to smile for nine years. And Spot and old Red had died slow, too.”

The girl jerked in a little, gasping breath, and then the Kid went on:

“I got a job digging and mucking around in the mine. It was about the

last honest work that I did in my life!”

He looked at the girl, and she looked straight back at him, studious and

noncommittal.

“While I was working, I spent the evenings and Sundays and all my wages

burning up gunpowder. My father had raised me with a gun in my hand, and

besides, I had a natural talent. People in that camp got to know me. They

used to come out and watch me shoot, and laugh as I missed. Then there

were competitions in the camp, pretty often. Shooting at marks of all

kinds, you know. But I stayed away from them until I had my hand well in.

Then I found a Saturday afternoon, when Turk was trying out his own hand,

and showing up a lot of the boys. They were shooting at an ax slash on

the breast of a tree. The tree was pretty well peppered, but Turk was the

only one who had nicked the mark. So I took my turn, and snaked three

bullets into that ax cut in quick time. That’s not boasting,” he added.

“I’m only fair with a rifle, but I can hit nearly anything with a

revolver—up to about twenty yards. This shooting attracted a good deal

of attention, and when I’d landed the three slugs in the mark, I turned

and smiled at Turk—I mean to say, I smiled so that the rest of the boys

could see me. He got pretty hot. He tried to laugh the thing off, but the

men stood around and watched, and waited. I thought that he’d pull a gun

on me, but he didn’t.

“After that, I still kept on in the camp for months. I haunted Turk. I

haunted him so that he never knew when I’d show up. I stood around and

smiled at him, with a sneer in my eyes; and I’d measure him up and down.

The boys began to be interested. They waited for something to happen, and

Turk knew they were waiting. He wanted to get rid of me, but his nerve

was bad. He’d seen those three bullets go home. It had shaken him up a

good deal. He lost a lot of prestige in the camp, right away, but he

stayed on. They were a wild mob up there in those days, but Turk ruled

them. He was tougher than the toughest. The more afraid of me he

became—I mean, the more afraid of his idea of me—the harder he worked

to make trouble with the others. In that month, he picked three fights

that turned into shooting scrapes, and in those scrapes he sent four men

to the hospital, and one of them died there. In the hospital tent, I

mean. But every day Turk’s face grew thinner, and his eyes more hollow.

He wasn’t sleeping much at night. One evening he rushed into the shack

where I was sitting alone, and cursed me and told me that he’d come to

finish me. He was shaking. He was crazy with drink and with anger and

hysteria. So I laughed in his face. I told him that I didn’t intend to

fight him until there was a crowd to watch. I told him who I was then,

and how the cows had died, and then my mother and my father. I told him

that I was going to make him burn on a slow fire, and when I chose to

challenge him, he’d take water, and take it before a crowd.”

“Good heavens!” said the girl. “Did he draw his gun on you, then?”

“No. He turned as green as grass, and backed through the door. He looked

as though he had been seeing a ghost. He ran off through the camp. I

think he was more than half crazy with fear. Superstitious fear, you

know. But the fellows that he started the fight with that night, they

simply thought that he was crazy drunk. They shot him to pieces, and that

was the end of Turk Reming. Do you want any more?

“Harry Dill was a fellow with a lot of German blood in him. And he had

the sort of a face you often see among Germans—round and pink-cheeked,

with the eyes and ears sticking out a good deal. He’d given up guns and

taken to barkeeping. He had the most popular saloon in the town.

Everybody drank there. He’d about put the two older places out of

business. He knew everybody in town by a first name or a nickname. He had

a house, he had a wife, he had a pair of children with round, red faces.

His wife was a nice Dutch girl, with a freckled, stub nose. She was

scrubbing and shining up her house and her children all day long. And she

kept Harry as neat as a pin. That was the way he was fixed when I walked

into his bar, one day. I beckoned him down to the end of the bar. He came

down, still laughing at the last story he had been telling, and wiping

the beer foam from his lips. He wheezed a little; he was shaking with

good nature and fat.

“So I leaned across the bar and told him in a whisper who I was, and what

I’d come for.”

“Did you tell him that you’d come to kill him?”

“Yes. I told him that. But I told him that I hadn’t yet figured out the

best way to do it. I would take my time, and in the meantime, I’d come in

and visit his place every day. It was hard on poor Harry. He couldn’t be

jolly when I was around. I used to sit in a dark corner, where I could

hardly be seen, but Harry was always straining his eyes at that corner.

He’d break off in the midst of his stories. When people told him jokes,

he couldn’t laugh. He simply croaked. He got absent-minded. And there’s

nothing that people hate more than an absent-minded bartender. Some of

his old cronies still came around, but in three days, that bar was hardly

attended at all. The cronies would tell him that he was sick, and ought

to take liver pills, but that wasn’t what was on Harry’s mind.

“He knew that I was the trouble, and he made up his mind to get rid of

me. So he sent a couple of boys around to call on me one evening.

However, I was expecting visitors. I persuaded them to confess how much

he’d paid them, and how much more he had promised. They wrote out

separate confessions and signed them. Then they got out of town.”

“How did you persuade them?” asked the girl. “You mean that they tried to

murder you?”

“They came in through the window,” said the Kid. “They came sneaking

across the room toward the bed where I was supposed to be lying, and

pretty soon they stepped on the matting. And I’d covered that matting

with glue. In two seconds they were all stuck together; and then I

lighted the lamp.”

He chuckled. The girl, however, did not laugh. She merely nodded, her

eyes narrowing.

“The next day,” went on the Kid, “I strolled over to the bar and read

those two confessions aloud to Harry Dill. He took it rather hard. He’d

turned into fat and beer, in those ten years or so since he’d been a

bold, bad horse thief and baby murderer. He got down on his knees, in

fact. But I only told him that I was still busy figuring out the best way

to get rid of him.

“This went on for another ten days. Harry Dill turned into a ghost. I

used to go in there and find him standing alone, his head on his hands.

He tried to talk to me. He used to cry and beg. On day his wife came to

me. She didn’t know what the trouble was, but she knew that I was it. She

begged me to leave her Harry alone, he was so dear and good! I read her

the two confessions, and she went off home with a new idea in her head. A

little after that, Harry offered me a glass of beer in his saloon. I took

it and poured some out for his dog, and the dog was dead in half an hour.

“That upset Harry some more. He was very fond of that dog! And, after I’d

been two weeks in town, poor Harry shot himself one evening. He’d been

having a little argument with his wife, the children testified.”

“And the poor little youngsters!” cried the girl, her heart in her voice.

“Oh, they had a good mother and a fine fat uncle, who took them all in,

and they were happy ever after. Do you want any more?”

She passed handkerchief across her forehead.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I didn’t think that it was going to be like

this.”

“Is it going to make you feel a lot closer and more friendly?” he asked,

with a faint and sardonic smile.

“It makes me shudder,” she admitted, “but I’d like to hear some more. Do

you mean that you drove every one of those men to suicide, or something

like it?”

“If I had simply shot them down,” said the boy, “would that have been

punishment? Why should I get myself hanged for their sakes?”

“I suppose not,” she answered. “Who was next?”

“The next was a sheriff,” said the Kid. “I’ve had a good deal of

experience with sheriffs, but, take them by the large, I’ve found them an

honest lot—very! But there are exceptions. And Chicago Oliver was one of

them. He wasn’t calling himself Chicago Oliver any more, when I found

him. No, he had a brand-new name, and it was a good one in the county

where he was living. They swore by their sheriff; he was the greatest man

catcher that they’d ever had. Of course he was, because he loved that

sort of business. Particularly when he had the law to help him.

“I met the sheriff on the

Comments (0)