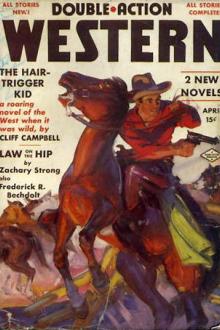

The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗». Author Max Brand

and I’ve always seen you, and I’ve always gone away. Since that day, when

I was fifteen, you’ve been in my mind as clearly as a thing learned by

heart when you’re very young.”

“I don’t exactly know what you’re trying to say,” said the girl.

“You know very well,” said the Kid, “what I want to say. And you know

that I won’t say it.”

He stood up before her. For out of the distance the melancholy sound grew

from the horizon, and suddenly she saw that with more than half his mind

he was listening to it. It was the lowing of the thirst-tormented cattle

by Hurry Creek.

“Whatever happens,” said the Kid, “you see that I’ve put my cards face up

on the table. I suppose you’d better show them to your father.”

In the sunset of that day, the black mare and the silver stallion stood

on the crest of a hill overlooking the big hollow through which Hurry

Creek ran from ravine to ravine. The light was growing dim, but still

there was enough of it for the Kid and Bud Trainor to see quite clearly.

There was a continual shifting and flowing, as it seemed, of the very

ground that led down toward the water. It was the troubled maneuvering of

masses upon masses of thirsty cattle. Still, from the outer reaches of

the ranch, the cattle were drifting in toward the familiar watering

place. They could be seen coming, sometimes singly, sometimes in patient

files that went one behind the other, winding across the well-worn

trails. From the hills on top of which they had a view of the creek,

these approaching animals were sure to send out a deep lowing as they

were made aware of a new and unprecedented condition there by the water

which was life to them.

Sometimes they seemed frightened and remained a long time to gaze.

Sometimes they grew excited, and breaking into a gallop, rushed up to

join the mob.

There was no sense in them. The cunning of long years on the range was

burned out of them. They were simply stupid creatures driven by an inward

fire. The bellowing, like the noise of a sea, was so deep and thunderous

that at times it seemed far off, and at times it rushed on the ear as

though the entire herd were stampeding in the direction of the watchers.

Now and then one of the milling currents stumbled on something, like

rapid water flowing over a rock; and there was no need for the Kid or Bud

Trainor to tell one another what those obstacles were.

Not fifty yards away from them lay a dead cow, with her legs sticking

straight out, as though she had been shot through the brain and had

tumbled over upon her side. And upon her head sat a buzzard looking in

the sunset light as big as a deformed child. Other buzzards were in the

air, though perhaps the near presence of the two riders prevented any of

them from joining their companion on the dead cow. But whole drifts of

those wonderful flyers sailed low above Hurry Creek, sweeping and sailing

without a flap of wings just above the dust cloud which rolled over the

heads of the cows and was drawn slowly off on the westering wind.

Through that mist of dust, they could see the surface of Hurry Creek

running red as blood under the sunset, and on the farther bank there was

already the shine of a camp fire which grew brighter as the light of the

day decreased.

There were Champ Dixon’s men making themselves comfortable, and even

jolly, no doubt, in the midst of this scene of unspeakable misery and

horror.

“That’s the way with gents,” philosophized Bud Trainor. “You can get a

man into a frame of mind for pretty nigh anything. Murder, say. You can

get the best sort of people to go to war, and there they’ll do all the

murderin’ they can get a chance to lay their hands on. How many of ‘em

would stay honest if just the right, safe chance to steal come and nudged

‘em in the ribs? Look at me. I sold you right in my own house.”

“Bud, never speak of that again,” said the Kid.

“You want that I should forget it, but even if I don’t talk, it’s in my

head, all day, every day, all night, every night.”

“Don’t be a fool,” said the Kid.

“I ain’t gonna be. But I’m gonna find a way to pay back. I’m gonna find a

way to make it right with you, Kid. That’s all I’ve gotta say, and I’ll

never mention it again!”

He snapped his jaws on the last word.

“What’s murder of men?” demanded the Kid. “Men have brains. They have

wits enough to hit back. They have guns to help ‘em. But a horde of dumb

beasts—that’s what I don’t understand, Bud. Dumb beasts that have done

no wrong, because they don’t know enough to do wrong. Look at them there!

There’ll be plenty of crow food on that ground before the morning. Bud!”

“Maybe the boys’ll rush ‘em before the morning,” suggested Bud.

He gestured to either side.

Keeping to the ridges of the hills that made the rim of the bowl through

which the creek flowed, all the punchers of the ranch were riding. Slowly

they went up and down, never offering to do anything, except keep a

sentry beat. But those dark figures, moving black against the sunset sky,

were grim enough, and suggestive of the dark passion that was in the

heart of every man of them.

“No,” said the Kid. “They know the sort of stuff that’s down there in the

hollow, and they won’t rush. Not them!”

He sneered as he spoke.

His voice was rising. His excitement also flashed and glittered in his

eyes.

“You’d think,” said Bud Trainor, wondering, “that you owned all of those

cows, and loved ‘em, too!”

“If I were the devil,” said the Kid, “I’d get on the backs of these cows

and put hell fire into their hearts. I’d run them in a mob on those

fences and smash ‘em down, and I’d charge them right onto the men and

stamp ‘em into a big bloodstain in the mud. I’d do it, and I’d enjoy

doing it. They’re dying, Bud. They’re dying tonight, but when the heat of

the sun comes tomorrow, they’ll drop like flies—all the ones that have

been off on the edges of the ranch, already without water for days.”

“They’ll drop like flies,” agreed Bud Trainor. “There ain’t any doubt

that they’ll drop like flies.”

“You’d think,” said the Kid, “that there wasn’t a God, when things like

this go on!”

“Look here. Kid,” said Trainor, “you’ve raised your own share of hell in

the world.”

“I’ve raised my share, and harvested it, too,” admitted the Kid, “and

sacked it, and put it away for the winter. I’ve raised my share, and

maybe I’ll raise some more, but not till I’ve tried my hand with this

job!”

“Hold on,” said Bud Trainor. “How can you try your hand—what job d’you

mean?”

The Kid looked sourly on him. His handsome young face was so dark with

anger that he seemed ten years older.

“This job in front of us,” said the Kid. “I’m going to get those cows to

water in the morning, or else I’ll throw some lead into Dixon’s boys as a

fair exchange.”

“Don’t be a fool,” cautioned Trainor, alarmed. “They have the law with

them. Even the sheriff admits that.”

“The heck with the law,” said the Kid. “I’m thinking of dying cows. One

wag of their tails is worth all the lives of those dirty crooks yonder!”

“Hold on, Kid. What’s your idea?”

“I’ve got no idea.”

“You’ve got none?”

“But I’ll get one before long.”

“Where? Where’ll you get an idea for the fixing of this job?”

“Oh, I dunno. From the devil maybe, or heaven above. But the idea is sure

to come!”

The scene was darkening. The river tarnished and turned black. The fog of

dust which rolled up from the milling cows now was Iessening, though now

and again the wind drifted a throat-stinging billow of it toward the

watchers.

The cattle by this time were becoming more quiet. Numbers of them lay

down. Only some hundreds of those most desperate with thirst came

sweeping up and down the lines of the fences. The thunder of the

bellowing was far less, but still from the hills behind, the newcomers

gave voice like mournful drums in a great and scattering chorus.

There was this difference with the coming of the night, for while the

clearly seen tragedy of the day had been localized and limited, now the

darkness blanketed away the farther mountains and brought down only the

nearer hills like black and beastly watchers of suffering. The ocean roar

of pain went up against the sky and seemed to fill it. It seeped up from

the very ground which actually, or in suggestion, trembled beneath them.

Hurry Creek had seemed a little theater during the day where a tragedy

was being enacted. Now it included the entire world.

So it seemed to Bud Trainor, as he sat on his horse beside the Kid and

looked down on the darkening hollow.

“Suppose Dixon’s men wanted to get out of there,” said Bud. “They’d have

a hard time, I reckon!”

“Why should they want to leave?” said the Kid. “They’re holding out for

two hundred thousand dollars’ blackmail. That’s what they want, and as

long as they care to camp there, I don’t see them running very short of

beef, do you?”

The other nodded, and then sighed a little.

“Well,” said he, “I meant that if this were an Indian war, the red devils

would rather be strung around up here on the heights than to be down

there in the hollow.”

“That’s interesting, but not important,” said the Kid. “They could be

besieged there for six months, and never have to worry. And if they got

tired of that, they could break away. But there’s meat enough for them.”

“They haven’t much wood,” objected the other. “They’ve cleaned up the

brush and stacked it in the middle of their camp. You can still see the

head of it beside their cookin’ tent. But that ain’t enough wood for six

months’ fuel. Not for cooking for that many men! Besides, they wouldn’t

dare to touch one of the dead cows.”

“Why not?”

“Well, wouldn’t that make them thieves, and wouldn’t we have the law with

us, then? Wouldn’t Milman be able to raise the whole range to help him,

if they did as much as that?”

“You’re right,” said the Kid, “but they have plenty of provisions with

them in there. And—and—and—”

Here his voice faltered and trailed away.

Bud Trainor, for some reason, knew that a matter of importance was

filling the brain of his partner, and he held his breath in anticipation.

“Bud,” said the Kid at last, “I’m going down into that camp.

“All right,” said Bud. “Which recipe for walkin’ the air do you use?”

The Kid was silent.

“You might just stroll down through them mobs of cows,” said Bud Trainor.

“They wouldn’t do much more to you than a steam roller would.”

Then he added: “I dunno how else you could

Comments (0)