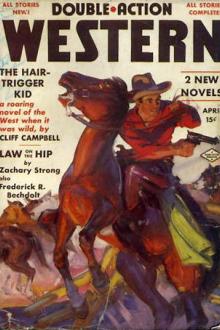

The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid, Max Brand [best classic literature TXT] 📗». Author Max Brand

the unexpected.”

He turned to his daughter.

“Georgia,” said he, “we’re talking business, your mother and I.”

“Yes, and miracles, I hear,” said Georgia, with the coldest of smiles.

“What do you mean, my dear?”

“Well, if you’re so interested in the Kid, I think you might like to know

that I’ve been talking to him.”

“You have? Where?”

“In the woods. In the clearing in the woods, nearest the house. We’ve

been talking for a long, long time.”

“I hope it was not a waste of time,” said Mrs. Milman, eying her daughter

narrowly.

“I never heard so many interesting things,” said she.

“Anything that we ought to know about, Georgia?”

“Well, one thing that would curdle your blood,” said the girl.

“And what was that?”

“Why,” said Georgia, studiously avoiding the eye of her father and giving

all of her attention to her mother, “when he was a little youngster of

six, his father and mother started to go to a new home—they were just

poor squatters, I take it—and when they got to the edge of the desert

with their few horses, and their mules, and their burro, and their

steers, and their pair of milk cows, along came a band of five scoundrels

and robbed them of everything, except the milk cows. Think of that!”

“A horrible thing,” said Mrs. Milman a little vacantly. “But we’re very

busy now, Georgia.”

Milman, with an odd pucker of his forehead, looked straight before him.

“You don’t understand how horrible it was, Mother,” said the girl. “The

poor little boy was sick, but his father insisted on trying to cross the

desert and get to the new country—the Promised Land to that poor man, I

suppose. So they pushed on. The boy grew more ill. The mother was half

mad with anxiety. It was a terrible march. They had yoked the milk cows

to the light wagon, you see. They lightened the load, throwing away

everything but a little food. Still it was hard going through the sand,

and the sun was terrible. It beat down, and one of the cows—old

Spot—was the first to drop. Then Red went staggering on for a couple of

days with the sick boy perched on her back. A frightful march, of

course.”

“Oh, what a ghastly thing!” said Elinore Milman, all the mother in her

roused.

“Well, old Red dropped dead too. But then they were in reaching distance

of the edge of the desert. They could see the green mist of the Promised

Land. They got through to it, all right. But the mother died in a short

time from the effects of that march. The father was broken-hearted, and

the Kid grew up with just one purpose in life—to find the five men who

had done the thing!”

“I hope that he has!” exclaimed Mrs. Milman. “I imagine that he’s the

sort of a fellow who would know how to handle them.”

“Yes, he got on the trail of them,” said the girl. “He spotted the stolen

mule nine years later.”

Here she let her glance drift across to the face of her father and she

saw his eyes widen, and then turn almost to stone. It was a frightful

moment.

If ever fear, grief, and sick consciousness of sin were in a face, it was

in that of the rancher just then.

She stared at him. She could have fallen to the floor with weakness and

with sorrow. And she was stunned by this second blow even more than when

the Kid had spoken to her.

Her mother, finally, attracted by the silence, looked curiously from one

of them to the other.

“A grisly story, John, isn’t it?” said she.

“Frightful!” said he.

And the word came hoarsely from his throat.

Elinore Milman stood up suddenly.

She faced her daughter and exclaimed: “Did he tell you the names of those

men?”

Georgia slumped back against the wall. She was dizzy. The room spun

before her eyes.

“He told me—four of them,” said she. “Four of them are dead.”

She roused herself suddenly. She had not meant to let her mother

understand, but Elinore Milman was now as white as marble. Her father was

like a man hanging upon a crucifix.

There was no use holding back now. She had said too much. Amazement at

her own folly in breaking out with the story before them both closed her

lips now. But her mother read her mind.

“I think,” said she, “that it’s just as well to have all sorts of things

out in the light of day. Family skeletons ought not necessarily to be

left in dark closets. Don’t you think so, John?” John Milman got to his

feet with a lurch and a stagger.

“I’m going out,” said he. “Need—little air.”

He went past his daughter but he was so blinded that he could not find

the handle of the door.

She had to open it for him, and then she watched him going down the hall

slowly, with many pauses, supporting himself with a weak hand against

first one wall and then the other.

He had been struck down as surely as by a thunderbolt.

And then she remembered what the Kid had done in all the other four

cases. There never had been any real use of guns. He had always struck

with other means.

And here, incredibly devilish though it was, he actually had delivered

his blow against Milman through the mouth of Milman’s own daughter.

She had been a mere tool, a foolish, incredible tool, but one with an

edge sharp enough to cut her father to the heart.

When Georgia turned back to her mother, she was met with a cold, keen

glance that startled her.

“That boy has been telling you a good deal, Georgia,” said Elinore

Milman.

“He told me because I asked,” said the girl.

“About your father?”

“No, but about what he had done and what he had been.”

“You’re interested in him, Georgia?”

The girl shrugged her shoulders.

“I think we’d better talk about father,” she said.

“Do you?” asked the mother, and lifted her brows a little.

It was a danger sign with which Georgia had been familiar for years.

“What does he matter,” said Georgia, “except that he’s a danger to

father?”

“That’s what I want to find out,” said Mrs. Milman. “I want to find out

what the Kid matters to you.”

“To me? Why, I’ve barely seen him.”

“That doesn’t matter very much—to him, I imagine. He’s been making love

to you, of course?”

“Of course not!” said Georgia.

Then she turned a bright crimson.

“Well?” said her mother, waiting.

“I suppose he did,” said the girl. “But not the way you’d think.”

“I don’t suppose that he asked you to marry him the first moment, if

that’s what you mean,” said Mrs. Milman, in the same quick, hard voice.

“But he’s been looking for you a long time, I suppose?”

Georgia, if possible, blushed still deeper. She began to feel that

probably even in this matter she had been made a fool of by the Kid. A

cold, deep pang of hatred for him slid through her.

“He’d seen me years ago,” said Georgia.

“Where?”

“Here. Through that window. One night when you were playing and I was

singing, and father was asleep.”

“And the Kid was looking about for whatever he could pick up?”

“He was looking for a mule with a barbed-wire scar across its chest. He’d

found Blister, Mother, and he’d followed Blister to our house.”

Mrs. Milman gripped hard on the arms of her chair. “That was a stolen

mule then.”

“Yes. According to the Kid.”

“I wish that we had some other name for him. Did he give you one?”

“No.”

“Georgia, what is this fellow to you?”

“I don’t know,” said Georgia, “except that I hate him more than any one

I’ve ever seen.”

“You like him better, too, don’t you?” asked the mother.

“Yes, I do.”

“What else did he tell you?”

“He told me how he had hunted down each one of the other four.”

“That must have been a pretty story.”

“He never touched one of them. He simply broke their hearts, one after

another.”

“Using other people for it—as he’s used you today?”

The girl lost her color at a stroke, but she answered steadily: “I see

that now.”

“How do you like him, Georgia?”

“I don’t know how to tell you.”

“It’s the great, romantic thrill, isn’t it?”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Oh, the big, handsome stranger with the strange life, and the rather

dark past. Isn’t that the thing? The Byronic touch, perhaps?”

“There isn’t much bunk about him,” said Georgia carefully.

She began to think, then she added: “No, there isn’t much pretense, so

far as I could see.”

“And how far do you think that you could see?”

“I don’t know. Perhaps not very far. I’m not pretending that I could look

through him.”

“The mystery is the attractive part, I suppose?”

“Perhaps that’s a part of it.”

“A good deal of pity, too, for the poor boy and his dead mother and

father?”

“I don’t think you really have a right to talk about that!” declared

Georgia.

Mrs. Milman suddenly closed her eyes.

“No,” she said, “I want to be fair. I’m simply trying to get at your

mind, Georgia.”

“I’ll try to tell you everything,” said Georgia.

She stood up like a soldier at attention. They had always been very close

friends.

“You know a good deal about the Kid, Georgia?”

“I know what he’s told me.”

“You believe it?” She pondered again.

“Yes,” she said. “Just now, at least, I believe every syllable of it.”

“What else do you know about him?”

“The rumors and the gossip, of course, not in much detail.”

“Such as what?”

“That he’s a gambler and a gunman.”

“Two easy words to repeat, But do you realize what they mean?”

“I think so. Not altogether, perhaps. I’m not a baby, though, Mother.”

“No,” said Mrs. Milman. “You’re not a baby, and you’ve reached the age

when you think you know, and think you think. Just try to remember that a

professional gambler is a fellow who matches his sleight of hand against

the honest chance which other players are trusting. And a gunman is a man

who takes advantage of his professional skill, his natural talent, to

pick quarrels with less-gifted men, and men who have something other than

murder to think about. What chance has the ordinary man against a skilled

gambler, or a trained gun fighter?”

The girl nodded.

“I’ve thought of those things. But I—”

“Well, but—”

“But I don’t believe that the Kid ever took an advantage.” Elinore Milman

made an impatient movement, but she controlled her voice as well as she

could.

“You seriously don’t, my dear?”

“I don’t,” said the girl. “It may be partly because he trusts himself so

perfectly. But I think that if he gambles, it’s against professional

gamblers, like himself. And if he fights, it’s with professional

fighters, like himself.”

A line of pain appeared between the

Comments (0)