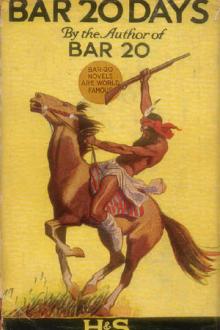

Bar-20 Days, Clarence E. Mulford [world best books to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Book online «Bar-20 Days, Clarence E. Mulford [world best books to read .TXT] 📗». Author Clarence E. Mulford

Mr. Elkins touched the glass to his bearded lips and set it down untasted while he joked over the sharp rebuff so lately administered to wire fences in that part of the country. While he was an ex-cow- puncher he believed that he was above allowing prejudice to sway his judgment, and it was his opinion, after careful thought, that barb wire was harmful to the best interests of the range. He had ridden over a great part of the cattle country in the last few yeas, and after reviewing the existing conditions as he understood them, his verdict must go as stated, and emphatically. He launched gracefully into a slowly delivered and lengthy discourse upon the subject, which proved to be so entertaining that his companions were content to listen and nod with comprehension. They had never met any one who was so well qualified to discuss the pros and cons of the barb-wire fence question, and they learned many things which they had never heard before. This was very gratifying to Mr. Elkins, who drew largely upon hearsay, his own vivid imagination, and a healthy logic. He was very glad to talk to men who had the welfare of the range at heart, and he hoped soon to meet the man who had taken the initiative in giving barb wire its first serious setback on that rich and magnificent southern range.

“You shore ought to meet Cassidy—he’s a fine man,” remarked Lucas with enthusiasm. “You’ll not find any better, no matter where you look. But you ain’t touched yore liquor,” he finished with surprise.

“You’ll have to excuse me, gentlemen,” replied Mr. Elkins, smiling deprecatingly. “When a man likes it as much as I do it ain’t very easy to foller instructions an’ let it alone. Sometimes I almost break loose an’ indulge, regardless of whether it kills me or not. I reckon it’ll get me yet.” He struck the bar a resounding blow with his clenched hand. “But I ain’t going to cave in till I has to!”

“That’s purty tough,” sympathized Wood Wright, reflectively. “I ain’t so very much taken with it, but I know I would be if I knowed I couldn’t have any.”

“Yes, that’s human nature, all right,” laughed Lucas. “That reminds me of a little thing that happened to me once—”

“Listen!” exclaimed Cowan, holding up his hand for silence. “I reckon that’s the Bar-20 now, or some of it—sounds like them when they’re feeling frisky. There’s allus something happening when them fellers are around.”

The proprietor was right, as proved a moment later when Johnny Nelson, continuing his argument, pushed open the door and entered the room. “I didn’t neither; an’ you know it!” he flung over his shoulder.

“Then who did?” demanded Hopalong, chuckling. “Why, hullo, boys,” he said, nodding to his friends at the bar. “Nobody else would do a fool thing like that; nobody but you, Kid,” he added, turning to Johnny.

“I don’t care a hang what you think; I say I didn’t an’—”

“He shore did, all right; I seen him just afterward,” laughed Billy Williams, pressing close upon Hopalong’s heels. “Howdy, Lucas; an’ there’s that ol’ coyote, Wood Wright. How’s everybody feeling?”

“Where’s the rest of you fellers?” inquired Cowan.

“Stayed home to-night,” replied Hopalong.

“Got any loose money, you two?” asked Billy, grinning at Lucas and Wright.

“I reckon we have—an’ our credit’s good if we ain’t. We’re good for a dollar or two, ain’t we, Cowan?” replied Lucas.

“Two dollars an’ four bits,” corrected Cowan. “I’ll raise it to three dollars even when you pay me that ‘leven cents you owe me.”

“‘Leven cents? What ‘leven cents?”

“Postage stamps an’ envelope for that love letter you writ.”

“Go to blazes; that wasn’t no love letter!” snorted Lucas, indignantly. “That was my quarterly report. I never did write no love letters, nohow.”

“We’ll trim you fellers to-night, if you’ve got the nerve to play us,” grinned Johnny, expectantly.

“Yes; an’ we’ve got that, too. Give us the cards, Cowan,” requested Wood Wright, turning. “They won’t give us no peace till we take all their money away from ‘em.”

“Open game,” prompted Cowan, glancing meaningly at Elkins, who stood by idly looking on, and without showing much interest in the scene.

“Shore! Everybody can come in what wants to,” replied Lucas, heartily, leading the others to the table. “I allus did like a six-handed game best—all the cards are out an’ there’s some excitement in it.”

When the deal began Elkins was seated across the table from Hopalong, facing him for the first time since that day over in Muddy Wells, and studying him closely. He found no changes, for the few years had left no trace of their passing on the Bar-20 puncher. The sensation of facing the man he had come south expressly to kill did not interfere with Elkins’ card-playing ability for he played a good game; and as if the Fates were with him it was Hopalong’s night off as far as poker was concerned, for his customary good luck was not in evidence. That instinctive feeling which singles out two duellists in a card game was soon experienced by the others, who were careful, as became good players, to avoid being caught between them; in consequence, when the game broke up, Elkins had most of Hopalong’s money. At one period of his life Elkins had lived on poker for five years, and lived well. But he gained more than money in this game, for he had made friends with the players and placed the first wire of his trap. Of those in the room Hopalong alone treated him with reserve, and this was cleverly swung so that it appeared to be caused by a temporary grouch due to the sting of defeat. As the Bar-20 man was known to be given to moods at times this was accepted as the true explanation and gave promise of hotly contested games for revenge later on. The banter which the defeated puncher had to endure stirred him and strengthened the reserve, although he was careful not to show it.

When the last man rode off, Elkins and the proprietor sought their bunks without delay, the former to lie awake a long time, thinking deeply. He was vexed at himself for failing to work out an acceptable plan of action, one that would show him to be in the right. He would gain nothing more than glory, and pay too dearly for it, if he killed Hopalong and was in turn killed by the dead man’s friends—and he believed that he had become acquainted with the quality of the friendship which bound the units of the Bar-20 outfit into a smooth, firm whole. They were like brothers, like one man. Cassidy must do the forcing as far as appearances went, and be clearly in the wrong before the matter could be settled.

The next week was a busy one for Elkins, every day finding him in the saddle and riding over some one of the surrounding ranches with one or more of its punchers for company. In this way he became acquainted with the men who might be called on to act as his jury when the showdown came, and he proceeded to make friends of them in a manner that promised success. And some of his suggestions for the improvement of certain conditions on the range, while they might not work out right in the long run, compelled thought and showed his interest. His remarks on the condition and numbers of cattle were the same in substance in all cases and showed that he knew what he was talking about, for the punchers were all very optimistic about the next year’s showing in cattle.

“If you fellers don’t break all records for drive herds of quality next year I don’t know nothing about cows; an’ I shore don’t know nothing else,” he told the foreman of the Bar-20, as they rode homeward after an inspection of that ranch. “There’ll be more dust hanging over the drive trails leading from this section next year when spring drops the barriers than ever before. You needn’t fear for the market, neither—prices will stand. The north an’ central ranges ain’t doing what they ought to this year—it’ll be up to you fellers down south, here, to make that up; an’ you can do it.” This was not a guess, but the result of thought and study based on the observations he had made on his ride south, and from what he had learned from others along the way. It paralleled Buck’s own private opinion, especially in regard to the southern range; and the vague suspicions in the foreman’s mind disappeared for good and all.

Needless to say Elkins was a welcome visitor at the ranch houses and was regarded as a good fellow. At the Bar-20 he found only two men who would not thaw to him, and he was possessed of too much tact to try any persuasive measures. One was Hopalong, whose original cold reserve seemed to be growing steadily, the Bar-20 puncher finding in Elkins a personality that charged the atmosphere with hostility and quietly rubbed him the wrong way. Whenever he was in the presence of the newcomer he felt the tugging of an irritating and insistent antagonism and he did not always fully conceal it. John Bartlett, Lucas, and one or two of the more observing had noticed it and they began to prophesy future trouble between the two. The other man who disliked Elkins was Red Connors; but what was more natural? Red, being Hopalong’s closest companion, would be very apt to share his friend’s antipathy. On the other hand, as if to prove Hopalong’s dislike to be unwarranted, Johnny Nelson swung far to the other extreme and was frankly enthusiastic in his liking for the cattle scout. And Johnny did not pour oil on the waters when he laughingly twitted Hopalong for allowing “a licking at cards to make him sore.” This was the idea that Elkins was quietly striving to have generally accepted.

The affair thus hung fire, Elkins chafing at the delay and cautiously working for an opening, which at last presented itself, to be promptly seized. By a sort of mutual, unspoken agreement, the men in Cowan’s that night passed up the cards and sat swapping stories. Cowan, swearing at a smoking lamp, looked up with a grin and burned his fingers as a roar of laughter marked the point of a droll reminiscence told by Bartlett.

“That’s a good story, Bartlett,” Elkins remarked, slowing refilling his pipe. “Reminds me of the lame Greaser, Hippy Joe, an’ the canned oysters. They was both bad, an’ neither of ‘em knew it till they came together. It was like this… .” The malicious side glance went unseen by all but Hopalong, who stiffened with the raging suspicion of being twitted on his own deformity. The humor of the tale failed to appeal to him, and when his full senses returned Lucas was in the midst of the story of the deadly game of tag played in a ten-acre lot of dense underbrush by two of his old-time friends. It was a tale of gripping interest and his auditors were leaning forward in their eagerness not to miss a word. “An’ Pierce won,” finished Lucas; “some shot up, but able to get about. He was all right in a couple of weeks. But he was bound to win; he could shoot all

Comments (0)