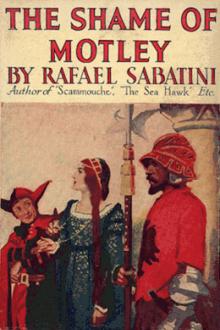

The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

Ramiro watched my advance with a smile in which mockery was blent with satisfaction, for all that of the resumption of my proper raiment he seemed to take no heed. No doubt he had dined well, and he was now disposing himself to be amused.

“Messer Bocadaro,” said he, when I had come to a standstill, “there was last night a matter that was not cleared up between us and concerning which I expressed an intention of questioning you to-day. I should proceed to do so at once, were it not that there is yet another matter on which I am, if possible, still more desirous you should tell us all you know. Once already have you evaded my questions with answers which at the time I half believed. Even now I do not say that I utterly disbelieve them, but I wish to assure myself that you told the truth; for if you lied, why then we may still be assisted by such information the cord shall squeeze from you. I am referring to the mysterious disappearance of Madonna Paola di Santafior—a disappearance of which you have assured me that you knew nothing, being even in ignorance of the fact that the lady was not really dead. I had confidently expected that the party searching for Madonna Paola would have succeeded ere this in finding her. But this morning my hopes suffered disappointment. My men have returned empty-handed once more.”

“For which mercy may Heaven be praised!” I burst out.

He scowled at me; then he laughed evilly.

“My men have returned—all save three. Captain Lucagnolo with two of his followers, has undertaken to go beyond the area I appointed for the search, and to proceed to the village of Cattolica. While he is pursuing his inquiries there, I have resolved to pursue my own here. I now call upon you, Boccadoro, to tell us what you know of Madonna Paola’s whereabouts.”

“I know nothing,” I answered stoutly. “I am prepared to take oath that I know nothing of her whereabouts.”

“Tell me, then, at least,” said he, “where you bestowed her.”

I shook my head, pressing my lips tight.

“Do you think that I would tell you if I had the knowledge?” was the scornful question with which I answered him. “You may pursue your inquiries as you will and where you will, but I pray God they may all prove as futile as must those that you would pursue here and upon my own person.”

This was how I fenced with him, this was the manner in which I followed Mariani’s sound advice that I should temporise! Oh! I know that my words were the words of a fool, yet no fear that Ramiro would inspire me could have restrained them.

There was a murmur at the table, and his fellows turned their eyes on Ramiro to see how he would receive this bearding. He smiled quietly, and raising his hand he made a sign to the executioners.

Rude hands seized me from behind, and the doublet was torn from my back by fingers that never paused to untruss my points.

They turned me about, and hurried me along until I stood under the pulleys of the torture, and one of the men held me securely whilst the other passed the cords about my wrists. Then both the executioners stepped back, to be ready to hoist me at the Governor’s signal.

He delayed it, much as an epicure delays the consumption of a delectable morsel, heightening by suspense the keen desire of his palate. He watched me closely, and had my lips quivered or my eyelids fluttered, he would have hailed with joy such signs of weakness. But I take pride in truthfully writing that I stood bold and impassively before him, and if I was pale I thank Heaven that pallor was the habit of my countenance, so that from that he could gather no satisfaction. And standing there, I gave him back look for look, and waited.

“For the last time, Boccadoro,” he said slowly, attempting by words to shake a demeanour that was proof against the impending facts of the cord, “I ask you to remember what must be the consequences of this stubbornness. If not at the first hoist, why then at the second or the third, the torture will compel you to disclose what you may know. Would you not be better advised to speak at once, while your limbs are soundly planted in their sockets, rather than let yourself be maimed, perhaps for life, ere you will do so?”

There was a stir of hoofs without. They thundered on the planks of the drawbridge and clattered on the stones of the courtyard. The thought of Cesare Borgia rose to my mind. But never did drowning man clutch at a more illusory straw. Cold reason quenched my hope at once. If the greatest imaginable success attended Mariani’s journey, the Duke could not reach Cesena before midnight, and to that it wanted some ten hours at least. Moreover, the company that came was small to judge by the sound—a half-dozen horses at the most.

But Ramiro’s attention had been diverted from me by the noise. Half-turning in his chair, he called to one of the men-at-arms to ascertain who came. Before the fellow could do his bidding, the door was thrust open and Lucagnolo appeared on the threshold, jaded and worn with hard riding.

A certain excitement arose in me at sight of him, despite my confidence that he must be returning empty-handed.

Ramiro rose, pushed back his chair and advanced towards the new-comer.

“Well?” he demanded. “What news?”

“Excellency, the girl is here.”

That answer seemed to turn me into stone, so great was the shock of this sudden shattering of the confidence that had sustained me.

“My search in the country failing,” pursued the captain, as he came forward, “I made bold to exceed your orders by pushing my inquiries as far as the village of Cattolica. There I found her after some little labour.”

Surely I dreamt. Surely, I told myself, this was not possible. There was some mistake. Lucagnolo had drought some wench whom he believed to be Madonna Paola.

But even as I was assuring myself of this, the door opened again, and between two men-at-arms, white as death, her garments stained with mud and all but reduced to rags, and her eyes wild with a great fear, came my beloved Paola.

With a sound that was as a grunt of satisfaction, Ramiro strode forward to meet her. But her eyes travelled past him and rested upon me, standing there between the leather-clad executioners with the cords of the torture pinioning my wrists, and I saw the anguish deepen in their blue depths.

Across the length of that hall our eyes met—hers and mine—and held each other’s glances. To me the room and all within it formed an indistinct and misty picture, from out of which there clearly gleamed my Paola’s sweet, white face.

All at the table had risen with Ramiro, and now, copying their leader, they bared their heads in outward token of such respect as certainly would have been felt by any men less abandoned than were they before so much saintly beauty and distress.

Lucagnolo had stepped aside, and Ramiro was now bowing low and ceremoniously before Madonna. His face I could not see, since his back was towards me, but his tones, as they floated across the hall to where I stood, came laden with subservience.

“Madonna, I give praise and thanks to Heaven for this,” said he. “I was afflicted by the gravest misgivings for your safety, and I am more than thankful to behold you safe and sound.”

There was a hypocritical flavour of courtliness about his words, and a mincing of his tones that suggested the efforts of a bull-calf to imitate the warbling of a throstle.

Madonna paid him no heed; indeed, she appeared not to have heard him, for her eyes continued to look past him and at me. At last her lips parted, and although she scarcely seemed to raise her voice above a whisper, the word uttered reached my ears across the stillness of the great room, and the word was “Lazzaro!”

At mention of my name, and at the tone in which it was uttered—a tone that betrayed same measure of what was in her heart—Ramiro wheeled sharply in my direction, his brows wrinkling. A certain craftiness he had, for all that I ever accounted him the dullest�witted clod that ever rose to his degree of honour. He must have realised how expedient it was that in all he did he should present himself to Madonna in a favourite light.

“Release him,” he bade the executioners that held me, and in an instant I was set free. The order given, he turned again to Madonna.

“You have been torturing him,” she cried, and her words were hard and fierce, her eyes blazing. “You shall repent it, Ser Ramiro. The Lord Cesare Borgia shall hear of it.”

Her anger betrayed her more and more, and however hidden it may have been to her, to me it was exceeding clear that she was encompassing my destruction. Ramiro laughed easily.

“Madonna, you are at fault. We have not been torturing him, though I confess that we were on the point of putting him to the question. But your timely arrival has saved his limbs, for the question we were asking him concerned your whereabouts!”

I would have shouted to her to be wary how she answered him, for some premonition how he was about to trick her entered my mind. But realising the futility of such a course, I held my peace and waited agonisedly.

“You had tortured him in vain then,” she answered scornfully. “For Lazzaro Biancomonte would never have betrayed me. Nor could he have betrayed me if he would, for after your men had searched the hut in which I was hidden, I walked to Cattolica thinking foolishly that I should be safer there.”

Lackaday! She had told him the very thing he had sought to know. Yet to make doubly sure he pursued the scent a little farther.

“Indeed it seems to me that had I tortured him I had given him no more than he deserved for having abandoned you in that hut. Madonna, I tremble to think of the harm that might have come to you through that knave’s desertion.” And he scowled across at me, much as the Pharisee might have scowled upon the publican.

“He is no knave,” she answered, and I could have groaned to hear her working my undoing, though not by so much as a sign might I inspire her with caution, for that sign must have been seen by others. “Nor did he abandon me. He left me only to go in quest of the necessaries for our journey. If harm has come to me the blame of it must not rest on him.”

“Of what harm do you speak, Madonna?” he cried, in a voice laden with concern.

“Of what harm,” she echoed, eyeing him with a scorn that would have slain him had he any manhood left. “Of what harm? Mother of Mercy, defend me! Do you ask the question? What greater harm could have come to me than to have fallen into the hands of Ramiro del’ Orca and his brigands?”

He stood looking at her, and I doubt not that his face was a very picture of simulated consternation.

“Surely, Madonna, you do not understand that we are your friends, that you can so abuse us. But you will be faint,

Comments (0)