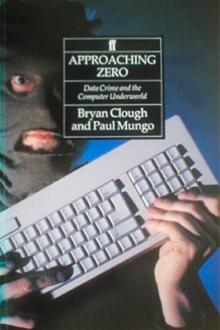

Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗

- Author: Paul Mungo

- Performer: -

Book online «Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗». Author Paul Mungo

that could have grossed him over $7.5 million, assuming that each of the twenty

thousand recipients of the diskette had sent the “lifetime” license fee. More

realistically, it was estimated that one thousand recipients had actually

loaded the diskette after receiving it; but even if only those one thousand had

sent him the minimum license fee, he still would have earned $189,000.

The police also discovered a diskette that they believed Popp intended to send

out to “registered users” who had opted for the cheaper, $189 license. Far from

being an antidote, it was another trojan and merely extended the counter from

90 boot-ups to 365 before scrambling the hard disk. In addition, there was

evidence that the London mailing was only an initial test run: when Popp’s home

in Ohio was raided, the FBI found one million blank diskettes. It was believed

that Popp was intending to use the proceeds from the AIDS scheme to fund a

mass, worldwide mailing, using another trojan. The potential return from one

million diskettes is a rather improbable $378 million.

The police also had suspicions that Popp, far from being mentally unstable, had

launched the scheme with cunning and foresight. For example, he had purposely

avoided sending any of the diskettes to addresses in the United States, where

he lived, possibly believing that it would make him immune to prosecution under

American law.

But the case was never to come to trial. Popp’s defense presented evidence that

his mental state had deteriorated. Their client, his British lawyers said, had

begun putting curlers in his beard and wearing a cardboard box on his head to

protect himself from radiation. In November 1991 the prosecution accepted that

Popp was mentally unfit to stand trial. To this day, the Computer Crime Unit

has never successfully prosecuted a virus writer.

For Popp, whatever his motives and his mental state, the AIDS scheme was an

expensive affair—all funded from his own pocket. The postage needed to send

out the first twenty thousand diskettes had cost nearly $7,700, the envelopes

and labels about $11,500, the diskettes and the blue printed instruction

leaflets yet

another $11,500—to say nothing of the cost of registering PC Cyborg

Corporation in Panama, or establishing an address in London. To add insult to

injury, not one license payment was ever received from anyone, anywhere.

Popp’s scheme was not particularly well thought out. The scam depended on

recipients of his diskettes mailing checks halfway around the world in the hope

of receiving an antidote to the trojan. But, as John Austen said, “Who in their

right mind would send money to a post office box number in Panama City for an

antidote that might never arrive?” Or that may not be an antidote anyway.

It seems unlikely that anyone will ever again attempt a mass blackmail of this

type; it’s not the sort of crime that lends itself to a high volume, low cost

formula. It’s far more likely that specific corporations will be singled out

for targeted attacks. Individually, they are far more vulnerable to blackmail,

particularly if the plotters are aided by an insider with knowledge of any

loopholes. An added advantage for the perpetrators is the likely publicity

blackout with which the corporate victim would immediately shroud the affair:

every major corporation has its regular quota of threats, mostly empty, and a

well-defined response strategy.

But at present, hacking—which gives access to information—has proven to be

substantially more lucrative. Presentday hackers traffic in what the

authorities call access device codes, the collective name for credit card

numbers, telephone authorization codes, and computer passwords. They are

defined as any card, code, account number, or “means of account access” that

can be used to obtain money, goods, or services. In the United States the codes

are traded through a number of telecom devices, principally voicemail

computers; internationally, they are swapped on hacker boards.

The existence of this international traffic has created what one press report

referred to colorfully as “offshore data havens”—pirate boards where hackers

from different countries convene to trade Visa numbers for computer passwords,

or American Express accounts for telephone codes. The passwords and telephone

codes, the common currency of hacking, are traded to enable hackers to maintain

their lifeline—the phone—and to break into computers. Credit card numbers are

used more conventionally: to fraudulently acquire money, goods, and services.

The acquisition of stolen numbers by hacking into credit agency computers or by

means as mundane as dumpster diving (scavenging rubbish in search of the

carbons from credit card receipts) differs from ordinary theft. When a person

is mugged, for example, he knows his cards have been stolen and cancels them.

But if the numbers were acquired without the victim knowing about it, the cards

generally remain “live” until the next bill is sent out, which could be a month

away.

Live cards—ones that haven’t been canceled and that still have have credit on

them—are a valuable commodity in the computer underworld. Most obviously, they

can be used to buy goods over the phone, with the purchases delivered to a

temporary address or an abandoned house to which the hacker has access.

The extent of fraud of this sort is difficult to quantify. In April 1989

Computerworld magazine estimated that computer-related crime costs American

companies as much as $555,464,000 each year, not including lost manhours and

computer downtime. The figure is global, in that it takes in everything: fraud,

loss of data, theft of software, theft of telephone services, and so on. Though

it’s difficult to accept the number as anything more than a rough estimate, its

apparent precision has given the figure a spurious legitimacy. The same number

frequently appears in most surveys of computer crime in the United States and

is even in many government documents. The blunt truth is that no one can be

certain what computer fraud of any sort really costs. All anyone knows is that

it occurs.

154 APPROACHING ZERO [WYRWA ??????]

erably older than the 150 or so adolescent Olivers she gathered into her ring.

As a woman, she has the distinction of being one of only two or three female

hackers who have ever come to the attention of the authorities.

In 1989 Doucette lived in an apartment on the north side of Chicago in the sort

of neighborhood that had seen better days; the block looked substantial, though

it was showing the first signs of neglect. Despite having what the police like

to term “no visible means of support,” Doucette was able to provide for herself

and her two children, pay the rent, and keep up with the bills. Her small

apartment was filled with electronic gear: personal computer equipment, modems,

automatic dialers, and other telecom peripherals.

Doucette was a professional computer criminal. She operated a scheme dealing in

stolen access codes: credit cards, telephone cards (from AT&T, MCI, Sprint, and

ITT) as well as corporate PBX telephone access codes, computer passwords, and

codes for voicemail (VM) computers. She dealt mostly in MasterCard and Visa

numbers, though occasionally in American Express too. Her job was to turn

around live numbers as rapidly as possible. Using a network of teenage hackers

throughout the country, she would receive credit card numbers taken from a

variety of sources. She would then check them, either by hacking into any one

of a number of credit card validation computers or, more often, by calling a

“chat line” telephone number. If the chat line accepted the card as payment, it

was live. She then grouped the cards by type, and called the numbers through to

a “code line,” a hijacked mailbox on a voicemail computer.

Because Doucette turned the cards around quickly, checking their validity

within hours of receiving their numbers and then, more importantly, getting the

good numbers disseminated on a code line within days, they remained live for a

longer period. It was a very efficiently run hacker service industry. To

supplement her income, she would pass on card numbers to members of her ring in

other cities, who would use them to buy Western Union money orders payable to

one of Doucette’s aliases. The cards were also used to pay for an unknown

number of airline tickets and for hotel accommodation when Doucette or her

accomplices were traveling.

The key to Doucette’s business was communication—hence the emphasis on PBX and

voicemail computer access codes. The PBXs provided the means for

communication; the voicemail computers the location for code lines.

PBX is a customer-operated, computerized telephone system, providing both

internal and external communication. One of its features is the Remote Access

Unit (RAU), designed to permit legitimate users to call in from out of the

office, often on a 1-800 nunlher. and access a long-distance line after

punching in a short code on the telephone keypad. The long-distance calls made

in this way are then charged to the customer company. Less legitimate users—

hackers, in other words—force access to the RAU by guessing the code. This is

usually done by calling the system and trying different sequences of numbers on

the keypad until stumbling on a code. The process is timeconsuming, but

hackers are a patient bunch.

The losses to a company whose PBX is compromised can be staggering. Some

hackers are known to run what are known as “callsell” operations: sidewalk or

street-corner enterprises offering passersby cheap long-distance calls (both

national and international) on a cellular or pay phone. The calls, of course,

are routed through some company’s PBX. In a recent case, a “callsell” operator

ran up $1.4 million in charges against one PBX owner over a four-day holiday

period. (The rewards to “callsell” merchants can be equally enormous: at $10 a

call some operators working whole banks of pay phones are estimated by U.S. Iaw

enforcement agencies to have made as much as $10,000 a day.)

PBXs may have become the blue boxes for a new generation of phreakers, but

voicemail computers have taken over as hacker bulletin boards. The problem

with the boards was that they became too well known: most were regularly

monitored by law

enforcement agencies. Among other things, the police recorded the numbers of

access device codes trafficked on boards, and as the codes are useful only as

long as they are live—usually the time between their first fraudulent use and

the victim’s first bill—the police monitoring served to invalidate them that

much faster. Worse, from the point of view of hackers, the police then took

steps to catch the individuals who had posted the codes.

The solution was to use voice mail. Voicemail computers operate like highly

sophisticated answering machines and are often attached to a company’s

toll-free 1-800 number. For users, voicemail systems are much more flexible

than answering machines: they can receive and store messages from callers, or

route them from one box to another box on the system, or even send one single

message to a preselected number of boxes. The functions are controlled by the

appropriate numerical commands on a telephone keypad. Users can access their

boxes and pick up their messages while they’re away from the office by calling

their 1-800 number, punching in the digits for their box, then pressing the

keys for their private password. The system is just a simple computer,

accessible by telephone and controllable by the phone keys.

But for hackers voice mail is made to order. The 1-800 numbers for voicemail

systems are easy enough to find; the tried-and-true methods of dumpster diving,

social engineering, and war-dialing will almost always turn up a few usable

targets. War-dialing has been simplified in the last decade with the advent of

automatic dialers, programs which churn through hundreds of numbers, recording

those that are answered by machines or computers. The process is still

inelegant, but it works.

After identifying a suitable 1-800 number, hackers

Comments (0)