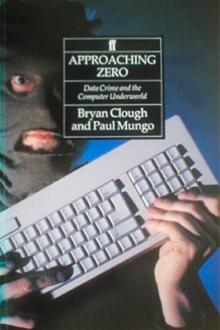

Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗

- Author: Paul Mungo

- Performer: -

Book online «Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗». Author Paul Mungo

hackers.

The Soviet secret service’s list of sites included the Pentagon, NORAD, the

research laboratories at Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos, Genrad in Dallas,

and Fermilab in Illinois, as well as MIT, Union Carbide, and NASA’s Jet

Propulsion Laboratory. It was a shopping list of top-secret defense

contractors and installations. The list continued with names of companies in

the U.K. and Japan. The KGB stipulated that it was interested in micro-electronics projects for military and industrial purposes—specifically in

programs for designing megachips, the electronic brains that were responsible

for the military strength of the Western allies. Two French companies in

particular attracted the KGB’s attention: Philips-France and SGSThomson, both

known to be involved in megachip research.

Koch knew that on the sites picked by the KGB he would be confronted with VAX

computers, which were made by DEC, but he had no experience with VMS, the

proprietary operating system used by VAXen. It was VAX expertise he was hunting

for at the Chaos congress: someone to make up for the skills he lacked.

It was lucky, then, that he met a seventeen-year-old hacker from West Berlin

named Hans Hubner. Hubner, a tall, slender young man with the paleness that

comes from staring at a computer screen too long, had been fascinated by

computers since he was a child. He was also addicted to an arcade game that

involved a little penguinlike character called Pengo. He liked it so much that

he adopted Pengo as his handle.

When he met Koch, Pengo was unemployed and desperately needed money. He also

shared Koch’s liking for drugs, but more important, he had experience with VMS.

Since 1985 he had been playing on Tymnet, an international computer network run

by the American defense contractor McDonnell Douglas, and had learned to use

the VAX default passwords—the standard account names that are included with

the machines when they’re shipped out from the manufacturer. Pengo was also one

of the first German hackers to break into CERN, the European Nuclear Research

Center in Geneva, Switzerland, and was a caller to the Altos bulletin board in

Munich—where, coincidentally, he had met Fry Guy, the Indiana hacker.

Koch befriended the young Berliner, invited him to Hannover, and introduced him

to Peter Kahl. Before long Pengo had become the second member of the gang,

operating from what was then West Berlin, while Koch continued his activities

in Hannover. Kahl later involved a contact in West Berlin, Dirk Brescinsky,

whose job it became to run Pengo.

Koch and Pengo had some early successes hacking into VAX machines. They

discovered that DEC’s Singapore computer center was exceptionally lax about

security. From there they were able to copy a VMS program called Securepack,

which allowed system managers to alter user status.

It was a useful piece of software for the KGB. But it wasn’t military data. To

get into defense sites, Pengo and Koch knew they needed to find a more certain

way into VAXen.

They didn’t have long to wait: within six months security on VAX systems

worldwide would be blown wide open.

Steffen Wernery became entangled in the conspiracy because of his peripheral

involvement in compromising VAX security. In the autumn of 1986 Hans Gliss, the

editor of Datenschutz-Berater who had been so helpful to Chaos over the Btx

affair, contacted Steffen. Gliss needed help and told the young hacker the

following story:

Gliss had been working as a consultant for SCICON, one of the largest computer

software companies in Germany. SCICON had been awarded a lucrative contract by

the government for work that was “very important, high security, requiring

maximum reliability.” It involved three networked VAX computers in three

locations, with the head office in Hamburg.

During the final phase of testing SCICON was contacted by a computer manager in

northern Germany and asked to explain the messages—short bursts of characters

and digits in no discernable order—that had been seen on his computers. From

the computerized routing information it was clear that the messages were

emanating from SCICON in Hamburg, but they made no sense to him or anyone at

his institute, or to anyone at SCICON.

The SCICON researchers checked through their security logs—computer files that

record all the comings and goings of users on the system—and quickly realized

that the dated and timed messages had all been originated “out-of-hours,” at

times when no authorized users would be active. Further investigation showed

that some new user IDs and passwords had been added to their system that no one

could account for. The implications, Gliss said, were all too obvious: hackers

had penetrated SCICON security and were using their computers as a launching

pad to other systems.

What Gliss now needed to know was if Steffen had any idea who might be

involved. If SCICON couldn’t guarantee the security of the system, the entire

contract with the German government would be at risk. Gliss needed to find out

who the hackers were, how they got on, and how to stop them. Contacting Steffen

was a long shot, but he was a leading member of Chaos and knew most of the

hackers in Germany. Perhaps he could make some calls.

Steffen thought about it: He reasoned that because the hackers were breaking

into the SCICON site in Hamburg, they were probably based in the city. It made

sense to call a nearby computer; that way the phone bills were cheaper.

Two days later he called Gliss and said that he had identified the hackers—two

Hamburg students. They had agreed to meet Gliss and help—provided that he

promise not to prosecute, so Gliss gave his word.

Later that week he met the two students, code-named Bach and Handel, in

Hamburg. Their story was worrying: the two students had exploited a

devastatingly simple flaw in the VMS operating system used on VAX. The

machines, like most computer systems, required users to log in their ID and

then type their password to gain access. If the ID or the password was wrong,

the VMS system had been designed to show an “error” message and bar entry. But

the two hackers told Gliss that if they simply ignored all the “error”

messages, they could walk straight into the system—provided they continued

with the log-on as though everything was in order. When confronted with the

“error” message after keying in a fake ID, they would press Enter, which would

take them to the password prompt. They would then type in a phony password,

bringing up a second, equally ineffectual “error” message. By ignoring it and

pressing Enter again, they were permitted access to the system. It was

breathtakingly easy, and left the VAX open to any hacker, no matter how

untalented.

For SCICON staff the situation was disastrous. To deliver their contract on

time, they would need to find the flaw in the operating system and fix it. At

first they turned to DEC for help, but with time running out, SCICON’s

programmers began looking for a solution themselves, tearing apart the VAX

operating system line by line. They were looking for a bug in the program that

would prevent it from operating correctly, or an omission in the commands that

would allow hackers to simply ignore the “error” message.

To the SCICON team’s surprise, they didn’t find one. What they discovered

instead was a piece of program code that appeared to have been deliberately

added to the operating system to provide the secret entrance. To the SCICON

researchers it looked like a deliberate “back door.”

Back doors are often left in computer programs, usually to facilitate testing.

Generally, they allow writers of things like computer games to jump quickly

through the program without having to play the game. For example, in the

mid-1980s a game called - Manic Miner involved maneuvering a miner level by

level from the depths of his mine up to the surface, the game becoming

progressively harder at each level. The programmer whose job it was to test the

game needed a shortcut between levels, so he introduced back doors that would

take him directly to any one of his choosing. Inevitably, some players stumbled

onto the hidden routes, which—ironically—increased the game’s popularity.

Often back doors, or “cheat modes,” are deliberately built into games,

encouraging the player to try to break the rules. Some computer magazines give

tips on how to find the cheat modes; some games, such as the popular Prince of

Persia, are said to be impossible to win without using them. Back doors might

also be introduced for more mercenary reasons: legend has it that programmers

include back doors on arcade games they create, and then supplement their

incomes by playing the games at venues such as nightclubs and casinos, which

offer prizes.

Some arcade back doors are well known. Occasionally, players stumble across

them by making some noninstinctive move: for example, on certain computer

gaming machines the instinct is to “hold” two lemons (if three lemons wins a

prize) and then spin for the third lemon. But this strategy almost never wins.

However, if the player doesn’t hold the two lemons and simply respins, the

three lemons will automatically come up. On another arcade

game, one which offers a sizable jackpot, it is said that the player brave

enough to refuse it and start the machine again will be rewarded by winning two

jackpots.

On a more sophisticated level, back doors are also provided on operating

systems for emergencies. Access to these back doors is reserved for the

computer manufacturer; procedures for gaining entry to the system from the

emergency back doors are highly confidential, highly complex, and not the sort

that could be stumbled over by accident.

The back door on the VAXen, though, was out in the open. It wasn’t simply for

emergencies; its security was far too trivial.

The VAX operating system, VMS, had been subjected to stringent tests and was

supposed to comply with the exacting “orange book” security standards

established by the U.S. Department of Defense. Under the orange-book testing

program, technically qualified intruders attempt to break through the security

features of a computer; the tests can take up to six months, depending on the

level of security required. It strained belief that VMS could have gone through

such testing without the back door being discovered.

Responding to complaints from its users, DEC issued a “mandatory patch,” a

small program designed specifically to close the back door, in May 1987. But

despite the “mandatory” order, many users didn’t bother to install it, and for

a short time, VAX computers across the world provided hackers with an open

house if they knew about the security gap.

Back doors are, of course, deliberate. They aren’t simple bugs in the program

or errors in the system: they are written by a programmer for a specific

purpose. In the case of the VAX back door, the who and why remains mysterious,

though it is clear that whoever created it had to have access to the VMS source

code, its basic operating instructions. One rather farfetched, though not

impossible, idea is that hackers broke into DEC and amended VMS to make it more

hospitable. Or perhaps a programmer put the commands in without the knowledge

of the company so that he could access VAX machines throughout the world

without IDs or passwords. Another more intriguing theory is that the back door

was built by the National Security Agency for its own use, though this

presupposes that the NSA is in the business of spying on computer users.

Yet some people do suppose precisely that. In their view it is a myth that the

NSA is interested in protecting computer security. Instead, it may be actively

engaged in penetrating computers or more bluntly, hacking—all over the world

by exploiting back doors that only the agency knows about.

Comments (0)