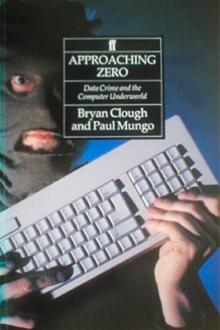

Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗

- Author: Paul Mungo

- Performer: -

Book online «Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗». Author Paul Mungo

In January 1990 Marcus Hess, Dirk Brescinsky, and Peter Kahl stood trial in

Celle, in northern Germany. Clifford Stoll and Pengo were witnesses for the

prosecution. The problem facing the court was establishing proof that anything

of value had been sold to the KGB. That was compounded by the fact that the

German police had neglected to apply for a judge’s consent for the wiretapping

of Hess. None of the material they had recorded “just in case” could be

admitted in court.

Without concrete proof that espionage on any significant scale had actually

occurred, the sentences were light. Hess received twenty months plus a fine of

about $7,000, Brescinsky fourteen months and about $3,500, and Kahl two years

and about $2,000. All the jail sentences were suspended and substituted with

probation.

Steffen Wernery is now thirty, an intense, outspoken man. He is calm about the

man whose activities caused him to spend sixty-six days in a French prison. His

ire is reserved for the French authorities, who, he says, have “no regard for

people’s rights.” His time in jail, he says, cost him $68,000 in lost income

and legal fees—roughly what the Soviet hacker gang earned in total from the

KGB. But he doesn’t blame Koch, and he doesn’t believe that he committed

suicide either:

Suicide did not make sense. It was unbelievable. Karl Koch had disclosed

himself to the authorities and had cooperated fully. He had provided them with

some good information and they had found him accommodations and a job with the

Christian Democratic party. He was also getting help with his drug dependency

and seemed on his way to rehabilitation. Murder seemed much more likely than

suicide. And there were many people who could have had a motive.

There was much speculation. He was murdered to prevent him testifying; it was a

warning to other hackers not to disclose themselves; perhaps it was even to

embarrass Gorbachev, who was due for a visit. Or perhaps to protect people in

high places.

After the unification of Germany the authorities gained access to police files

in what had been East Germany. According to Hans Gliss, who maintains close

contacts with the intelligence services, there was “a strong whisper” that the

Stasi—East Germany’s secret service—was responsible for Koch’s death. The

motive remained a mystery, though there were any number of arcane theories:

that the agency was jealous of Koch’s ties to the KGB; that they were

protecting the KGB from a source who was proving too talkative; that they

wanted to embarrass the KGB; that they had also been getting information from

Koch, and so on.

The Staatssicherheit, or Stasi, has acquired a formidable reputation. Its

foreign service, led by the legendary Marcus Wolf, was reported to have planted

thousands of agents in West Germany’s top political and social circles, most

notoriously Gunther Guillaume, who became private secretary to Chancellor Willy

Brandt. The revelation caused the fall of the Brandt government.

The Stasi has become a convenient villain: since the collapse of East Germany

the shadowy secret service’s reputation for skulduggery has grown to mythic

proportions. In mysterious cases, such as the death of Karl Koch, the sinister

hand of Stasi will be detected by all those who want to see it.

Nonetheless, murder can’t be ruled out. There is the evidence—the missing

shoes, the controlled fire—that suggests that another party was involved in

Koch’s death. Then there is the motive. Koch had little reason to kill himself.

He had a job; he was getting treatment for his drug problem. He was in no

danger of being prosecuted for his part in the “Soviet hacker” affair: like

Pengo, he would have been a witness for the prosecution, protected from

punishment by the terms of the amnesty provision. After the trial he would have

resumed his life (like Pengo, who is now married and living in Vienna).

Some who knew Koch think the young hacker got in over his head. He, Pengo, and

Hess were pawns in the espionage game, amateur spies recruited by the Soviets

to break into Western computers. It is now thought possible that the Soviets

were running other hackers at the same time, testing one gang against the

other. For the KGB, it was low-risk espionage: they paid for programs,

documents, and codes that would otherwise have been inaccessible—unless of

course their own operatives were prepared to sit for days or even weeks in

front of a computer, learning the rudiments of hacking.

It was an opportunistic intelligence-gathering operation. The Soviet hacker

gang had quite literally walked through the KGB’s front door, offering to sell

military secrets. Given that the agency paid $68,000 for the data, it must be

assumed they were satisfied with what they had received.

Espionage is a curious trade. Those who claim to know how intelligence agencies

work say that computer penetration has become a new and useful tool for

latter-day spies. The Americans are said to be involved, through the NSA, as

are the British, through GCHQ, the General Communications Headquarters, which

gathers intelligence from diverse sources. Hacking, at this rarefied level,

becomes a matter of national security.

Of course the Americans and the British aren’t the only ones suspected of

involvement. Mossad, the Israeli secret service, is said to have penetrated the

computer systems of French defense contractors who had sold weapons to its

enemies in the Middle East. The Israeli service then altered some of the data

for the weaponry, rendering it vulnerable to their own defense systems. In this

case, the Israelis may have been merely copying the French. During the Gulf War

it was widely reported that certain French missiles—the Exocets, which had

previously been sold to the Iraqis—included back doors to their computer

guidance systems. These back doors would allow the French military to send a radio signal

to the Exocets’ on-board computers, rendering the weapons harmless.

The scheme, neat as it appears, was never put to the test. The Iraqis never

used their Exocets during the conflict—perhaps because they, too, had heard

the stories. On the other hand, the entire scenario could well have been French

disinformation.

It was in this murky world of spying and double-cross that the Soviet hacker

gang found itself. In the wider sphere of international and industrial

espionage the Germans were ultimately only minor irritants. The technology now

exists to access the computer systems of competitors and rivals, and it would

be naive to presume that these methods are not being used. It is possible, for

instance, to read a computer screen with a radio signal from a site hundreds of

feet away. And, during the Cold War, a small truck believed to be equipped with

such a device was shipped from Czechoslovakia to Canada. It entered the United

States under the guise of diplomatic immunity and traveled, in a curious and

indirect way, to the Mexican border. The route took the van close to a sizable

number of American defense installations, where the driver would stop, often

for days. It was assumed by the small army of federal agents following the

truck that it was homing in on computer screens on the bases and sending the

material on to the Soviet Embassy in Washington.

It’s not known if the Czechs and the Soviets found any information of real

value, but with the increased use of technology, and the vulnerability of

networked computer systems, it is probable that corporations and governments

will be tempted to subvert or steal data from rivals. And, under these

circumstances, there is inevitably another explanation for the breakin at

Philips-France and SGSThomson. In 1986 and 1987 Mossad was becoming

increasingly worried about deliveries of French weaponry to Iraq and other Arab

states. Some of the electronic components for these weapons were designed at

the two companies. The Israelis wanted to destroy or steal the data for these

components, and to do so, hacked into the companies’ computers, using the same

techniques being used by the Germans. Mossad knew that the German hackers would

get the blame. Indeed, they knew that Pengo and Koch were wandering about the

same computers. But the two Germans wouldn’t have destroyed information—that

would have drawn attention to their activities; nor did they ever manage to

steal anything worth hundreds of millions of dollars. That was Mossad.

Koch, with his love of conspiracies, would have appreciated such a theory. The

Illuminati—the French police, the KGB, the Stasi and Mossad—were real after

all.

The Soviet hacker gang wasn’t the only reason for the subsequent U.S.

government crackdown on the computer underworld. But the threat of a

Communist plot to steal top-secret military data was enough to focus the

attention of the previously lethargic investigators. The federal authority’s

lack of urgency in dealing with what appeared to be a threat to national

security had been documented by Clifford Stoll in The Cuckoo’s Egg, and the

diffidence displayed by the FBI and the Secret Service in that case had caused

them a great deal of embarrassment. After Stoll’s disclosures, the authorities

began monitoring hacker bulletin boards much more closely.

One of the boards staked out by the Secret Service was Black ICE, the Legion of

Doom’s favorite, located somewhere in Richmond, Virginia. On March 4, 1989, two

days after the arrest of the Soviet hacker gang, intrigued Secret Service

agents recorded the following exchanges:

I SAW SOMETHING IN TODAY’S PAPER THAT REALLY BURNS ME, growled a Legionnaire

known as Skinny Puppy, initiating a series of electronic messages.’ He

continued:

SOME WEST GERMAN HACKERS WERE BREAKING INTO SYSTEMS AND SELLING INFO TO THE RUSSIANS. IT’S ONE THING

REINa A HACKER. IT’S ANOTHER BEING A TRAITOR. IF I FIND

OUT THAT ANYONE ON THIS BOARD HAD ANYTHING TO DO WITH IT, I WILL PERSONALLY

HUNT THEM DOWN AND MAKE THEM WISH THEY HAD BEEN BUSTED BY THE FBI. I AM CONSIDERING STARTING MY OWN INVESTIGATION INTO THIS INCIDENT AND DESTROYING A FEW

PEOPLE THE BKA [German federal police] DIDN’T GET. DOES ANYONE CARE TO JOIN ME

ON THIS CRUSADE? OR AT LEAST GIVE SUPPORT? CAN I CLAIM AN ACT UPON THESE CREEPS

AS LOD VENGEANCE FOR DEFILING THE HACKERS IMAGE?

An hour and a half later the Prophet uploaded his response:

DON’T FROTH AT THE MOUTH, PUPPY; YOU’LL PROBABLY JUST ATTRACT THE ATTENTION OF

THE AUTHORITIES, WHO SEEM TO HAVE HANDLED THIS WELL ENOUGH ON THEIR OWN. TOO

BAD THE IDIOTS AT NASA AND LOS ALAMOS COULDN’T HAVE DONE THE SAME. HOW MANY

TIMES ARE THEY GOING TO ALLOW THEIR SECURITY TO BE PENETRATED? HOW DO YOU THINK

THIS IS GOING TO AFFECT DOMESTIC HACKERS? MY GUESS IS, THE FEDS ARE GOING TO

RF.AR DOWN ON IJS HARDER.

The Highwayman, one of the bulletin board’s system operators, suggested, LET’S

BREAK INTO THE SOVIET COMPUTERS AND GIVE

THE INFO TO THE CIA. I KNOW YOU CAN GET ON A SOVIET PSN [Public

Switched Network, the public telephone system] FROM AN EAST

GERMAN GATEWAY FROM WEST GERMANY.

Other Legionnaires were less patriotic. Erik Bloodaxe said, TAKE MONEY ANY WAY

YOU CAN! FUCK IT. INFORMATION IS A VALUABLE COMMODITY, AND SHOULD BE SOLD. IF

THERE lS MONEY TO BE MADE, THEN MAKE IT. FUCK AMERICAN SECRETS. IT DOESN’T

MATTER. IP RUSSIA REALLY WANTED SOMETHING, THEY WOULD PROBABLY GET IT ANYWAY.

GOOD FOR WHOEVER SOLD IT TO THEM!

The last message was posted late that same night. THIS GOVERNMENT DESERVES TO

BE FUCKED, said the Urvile. I’M ALL FOR A

GOVERNMENT THAT CAN HELP ME (HEY, COMRADE, GOT SOME SECRETS FOR YOU CHEAP). FUCK AMERICA. DEMOCRACY lS FOR LOSERS.

DICTATORSHIP, RAH! RAH!

At this early date there were rumors that Chaos had been involved with the

Soviet hackers, even that some of its members had been arrested. One of the

Legionnaires

Comments (0)