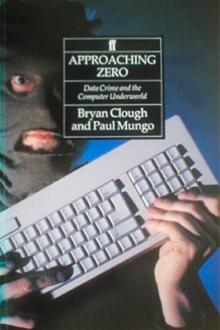

Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗

- Author: Paul Mungo

- Performer: -

Book online «Approaching Zero, Paul Mungo [good summer reads TXT] 📗». Author Paul Mungo

FBI. The effect has been to leave the two agencies to fight out their

responsibilities between themselves.

The Secret Service was already in the midst of an in-depth investigation of the

computer underworld. In 1988 the agency had become aware of a new proposal, one

that seemed to signal an increase in hacker activity. Called the Phoenix

Project, it was heralded in the hacker bulletin PHRACK as “a new beginning to

the phreak/hack community where knowledge is the key to the future and is free.

The telecommunications and security industries can no longer withhold the right

to learn, the right to explore, or the right to have knowledge.” The Phoenix

Project, it was announced, would be launched at SummerCon ‘88—the annual

hacker conference, to be held in a hotel near the airport in Saint Louis.

The Phoenix was the legendary bird that rose from its own ashes after a fiery

death. To the hackers it was just a name for their latest convention. But to

the telephone companies and the Secret Service, the Phoenix Project portended

greater disruption—as well as the theft of industrial or defense secrets. The

implications of “the right to learn, the right to explore, or the right to have

knowledge” appeared more sinister than liberating, and the article was

published just as the Secret Service was becoming aware of an upsurge in hacker

activity, principally telecommunications fraud. The increase appeared linked to

the hacker wars, then spluttering inconclusively along.

Coincidentally, in May 1988, police in the city of Phoenix, Arizona, raided the

home of a suspected local hacker known as the Dictator. The young man was the

system operator of a small pirate board called the Dark Side. The local police

referred his case to the district attorney for prosecution, and he in turn

notified the secret service.

No one was quite sure what to do with the Dictator—but then someone had the

bright idea of running his board as a sting. The Dictator agreed to cooperate:

in return for immunity from prosecution, he continued to operate the Dark Side

as a Secret Service tool for collecting hacker lore and gossip and for

monitoring the progress of the Phoenix Project. That the scheme to investigate

the Phoenix Project was based in the city of Phoenix was entirely coincidental:

it was established there solely because the local office of the Secret Service

was willing to run an undercover operation.

Dubbed Operation Sundevil, after the Arizona State University mascot, it was

officially described as “a Secret Service investigation into financial crimes

(fraud, credit card fraud, communications service losses, etc.) led by the

Phoenix Secret Service with task force participation by the Arizona U.S.

Attorney’s office and t he Arizona Attorney General’s office.” The Arizona

assistant attorney general assigned to the case was Gail Thackeray, an

energetic and combative attorney who would become the focal point for press

coverage of the operation.

But the impetus for Operation Sundevil—the Dark Side sting—only provided the

authorities with a limited insight into the computer underworld. Reams of

gossip and electronic messages were collected, but investigators were still no

nearer to getting a fix on the extent of hacking or the identities of the key

players. They decided on another trick: they enlisted the Dictator’s help in

penetrating the forthcoming SummerCon ‘88, the event that would launch the

Phoenix Project.

Less a conference and more a hacker party, SummerCon ‘88 was held in a dingy

motel not far from the Saint Louis airport. Delegates, usually adolescent

hackers, popped in and out of one another’s rooms to gossip and play with

computers.

The Dictator stayed in a special room, courtesy of the Secret Service. Agents

next door filmed the proceedings in the room through a two-way mirror,

recording over 150 hours of videotape. Just what was captured in this film has

never been revealed (the Secret Service has declined all requests to view the

tapes), but

cynics have suggested that it may be the most boring movie ever made—a six-day

epic featuring kids drinking Coke, eating pizzas, and gossiping.

Nonetheless, the intelligence gathered at SummerCon and through the Dark Side

had somehow convinced the Feds that they were dealing with a national

conspiracy, a fraud that was costing the country more than $50 million in

telecom costs alone. And that, said Gail Thackeray (boo hiss bitch!), was “just

the tip of the iceberg.”

Then the Phoenix Secret Service had a lucky break.

In May 1989, just a year after ousting the Dictator, police investigating the

abuse of a Phoenix hotel’s private telephone exchange stumbled across another

hacker. He was no small-time operator. Questioned by the Secret Service, he

admitted that he had access to Black ICE. He wasn’t an LoD member, he added,

merely one of the few non-Legionnaires allowed to use the gang’s board. Under

pressure from the Secret Service, who reminded him of the penalties for hacking

into a private telephone exchange and stealing services, he, too, agreed to

become an informant. He would be referred to only as Hacker 1.

A month later the Secret Service learned about the anonymous call to the

Indiana Bell security manager and the threat to the telephone switches. At this

stage there was still no evidence of an attack. Similar hoax calls are received

every day by the phone companies. But then, on July 3rd, four days after the

anonymous call, the Bellcore task force discovered that this wasn’t just an

idle threat. Three computer bombs were found, just hours before the Fourth of

July public holiday. The bombs, as the caller had warned, were spread across

the country: one was discovered in a switch in BellSouth in Atlanta, Georgia;

another in Mountain Bell’s system in Denver, Colorado; and the third in Newark,

New Jersey. The devices were described by the Secret Service as “time bomb[s] .

which if left undetected, would have compromised these computers (for an

unknown period) and effectively shut down the compromised computer telephone

systems in Denver, Atlanta. and New Jersey.” In ~lainer language, had the bombs

not been discovered and defused, they could have created local disasters.

In the Secret Service offices in Phoenix, the interrogation of Hacker 1

acquired more urgency. The agents now knew that somewhere out there was a

computer freak—or perhaps a gang of freaks—with the ability and inclination

to plant bombs in the telephone system. It could happen again, and the next

time there might not be any warning. The agents probed Hacker I about his

contacts in the Legion of Doom, particularly those Legionnaires who might have

access to the compromised phone companies.

He told them about the Urvile, the Leftist, and the Prophet, three members who

had the expertise to plant bombs, and were all based in Atlanta, the home of

BellSouth.

This information was enough for the Georgia courts to authorize the placing of

Dialed Number Recorders (DNRs) on the three hackers’ phone lines.

For ten days the Secret Service monitored every call and recorded the hackers

looping around the country to gain free telephone service and to avoid

detection. The Atlanta hackers often started their loops by dialing into the

computer system at Georgia Tech, using IDs and passwords provided by the

Urvile, a student there. From Georgia Tech they could tour the world, if they

felt the inclination, hopping from one network to another, wherever lax

security or their own expertise permitted. With the evidence from the DNRs, the

Secret Service executed search warrants on the three LoD members, and

eventually raided their homes.

The investigators uncovered thousands of pages of proprietary telephone company

information, hundreds of diskettes, half a dozen computers, and volumes of

notes. The three Legionnaires and their fellow hackers had been dumpster diving

at BellSouth, looking for telco manuals. With the information gleaned, they had

developed techniques for accessing over a dozen of BellSouth’s computer

systems, and from these they downloaded information that would allow them to

get into other computer systems—including those belonging to banks, credit

bureaus,

hospitals, and businesses. When the Leftist was interviewed, he nonchalantly

agreed that the Legionnaires could easily have shut down telephone services

throughout the country.

Among the masses of information that the investigators found were files on

computer bombs and trojan horses—as well as one document that described in

detail how to bring down a telephone exchange by dropping a computer program

into a 5ESS switch. The program simply kept adding new files to the switch’s

hard disk until it was full, causing the computer to shut down.

What the investigators didn’t uncover was any direct evidence linking the

Atlanta Three to the computer bombs. Simple possession of a report that details

how a crime could be committed does not prove that it has been. But they did

find one document that seemed to portend even greater destruction: during the

search of the Prophet’s home they discovered something called the “E911 file.”

Its significance escaped the Treasury agents, but it immediately caused the

technicians from BellSouth to blanch: “You mean the hackers had this stuff?”

The file, they said, described a new program developed for the emergency 911

service: the E simply stood for enhanced.

The 911 service is used throughout North America for handling emergency calls—

police, fire, and ambulance. Dialing 911 gives direct access to a

municipality’s Public Safety Answering Point, a dedicated telephone facility

for summoning the emergency services. The calls are carried over an ordinary

telephone switch; however, incoming 911 calls are given priority over all other

calls. From the switch, the 911 calls travel on lines dedicated to the

emergency services.

In March 1988 BellSouth had developed a new program for enhancing the 911

service. The E911 file contained information relating to installation and

maintenance of the service, and was headed, “Not for use or disclosure outside

BellSouth or any of its subsidiaries except under written agreement.” It had

been stored in a computer in BellSouth’s corporate headquarters in Atlanta,

Georgia. While hacking into the supposedly secure system, the Prophet had found

the file and downloaded it to his own PC.

In the hands of the wrong people, the BellSouth technicians said, the critical

E911 document could be used as a blueprint for widespread disruption in the

emergency systems. Clearly, hackers were the wrong sort of people. According to

BellSouth, “any damage to that very sensitive system could result in a

dangerous breakdown in police, fire, and ambulance services.” Mere computer

bombs seemed childish by comparison.

Just seven months later, on the public holiday in honor of Martin Luther King,

Jr., the most sophisticated telephone system in the world went down for nine

hours. At 2:25 P.M. on January 15,1990 the nationwide network operated by AT&T

was hit by a computer failure. For the duration of the breakdown, the only

voice responding to millions of long-distance callers was a recorded message:

“All services are busy—please try again later.”

It was estimated that by early afternoon as many as half the long-distance

calls being dialed in every major city were blocked. Some twenty million calls

were affected, causing chaos in many businesses, especially those such as

airlines, car rental companies, and hotels which rely on free 1-800 numbers. It

was the most serious failure since the introduction of computer-based phone

systems thirty years earlier.

Robert E. Allen, AT&T chairman, emerged the following day to explain that

“preliminary indications are that a software problem occurred, which spread

rapidly through the network.” Another spokesman said that while a failure in

the software systems was probably to blame, a computer bomb could not be ruled

out. The problem had been centered in what was called a signal node, a computer

or switch attached to the network. According to AT&T, the errant system “had

told switches it was unable to receive calls, and this had a domino effect on

Comments (0)