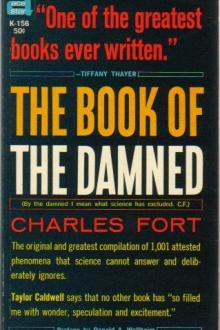

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

These three factors indicate, somewhere not far aloft, a region of inertness to this earth's gravitation, of course, however, a region that, by the flux and variation of all things, must at times be susceptible—but, afterward, our heresy will bifurcate—

In amiable accommodation to the crucifixion it'll get, I think—

But so impressed are we with the datum that, though there have been many reports of small frogs that have fallen from the sky, not one report upon a fall of tadpoles is findable, that to these circumstances another adjustment must be made.

Apart from our three factors of indication, an extraordinary observation is the fall of living things without injury to them. The devotees of St. Isaac explain that they fall upon thick grass and so survive: but Sir James Emerson Tennant, in his History of Ceylon, tells of a fall of fishes upon gravel, by which they were seemingly uninjured. Something else apart from our three main interests is a phenomenon that looks like what one might call an alternating series of falls of fishes, whatever the significance may be:

Meerut, India, July, 1824 (Living Age, 52-186); Fifeshire, Scotland, summer of 1824 (Wernerian Nat. Hist. Soc. Trans., 5-575); Moradabad, India, July, 1826 (Living Age, 52-186); Ross-shire, Scotland, 1828 (Living Age, 52-186); Moradabad, India, July 20, 1829 (Lin. Soc. Trans., 16-764); Perthshire, Scotland (Living Age, 52-186); Argyleshire, Scotland, 1830, March 9, 1830 (Recreative Science, 3-339); Feridpoor, India, Feb. 19, 1830 (Jour. Asiatic Soc. of Bengal, 2-650).

A psycho-tropism that arises here—disregarding serial significance—or mechanical, unintelligent, repulsive reflex—is that the fishes of India did not fall from the sky; that they were found upon the ground after torrential rains, because streams had overflowed and had then receded.

In the region of Inertness that we think we can conceive of, or a zone that is to this earth's gravitation very much like the neutral zone of a magnet's attraction, we accept that there are bodies of water and also clear spaces—bottoms of ponds dropping out—very interesting ponds, having no earth at bottom—vast drops of water afloat in what is called space—fishes and deluges of water falling—

But also other areas, in which fishes—however they got there: a matter that we'll consider—remain and dry, or even putrefy, then sometimes falling by atmospheric dislodgment.

After a "tremendous deluge of rain, one of the heaviest falls on record" (All the Year Round, 8-255) at Rajkote, India, July 25, 1850, "the ground was found literally covered with fishes."

The word "found" is agreeable to the repulsions of the conventionalists and their concept of an overflowing stream—but, according to Dr. Buist, some of these fishes were "found" on the tops of haystacks.

Ferrel (A Popular Treatise, p. 414) tells of a fall of living fishes—some of them having been placed in a tank, where they survived—that occurred in India, about 20 miles south of Calcutta, Sept. 20, 1839. A witness of this fall says:

"The most strange thing which ever struck me was that the fish did not fall helter-skelter, or here and there, but they fell in a straight line, not more than a cubit in breadth." See Living Age, 52-186.

Amer. Jour. Sci., 1-32-199:

That, according to testimony taken before a magistrate, a fall occurred, Feb. 19, 1830, near Feridpoor, India, of many fishes, of various sizes—some whole and fresh and others "mutilated and putrefying." Our reflex to those who would say that, in the climate of India, it would not take long for fishes to putrefy, is—that high in the air, the climate of India is not torrid. Another peculiarity of this fall is that some of the fishes were much larger than others. Or to those who hold out for segregation in a whirlwind, or that objects, say, twice as heavy as others would be separated from the lighter, we point out that some of these fishes were twice as heavy as others.

In the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 2-650, depositions of witnesses are given:

"Some of the fish were fresh, but others were rotten and without heads."

"Among the number which I got, five were fresh and the rest stinking and headless."

They remind us of His Grace's observation of some pages back.

According to Dr. Buist, some of these fishes weighed one and a half pounds each and others three pounds.

A fall of fishes at Futtepoor, India, May 16, 1833:

"They were all dead and dry." (Dr. Buist, Living Age, 52-186.)

India is far away: about 1830 was long ago.

Nature, Sept. 19, 1918-46:

A correspondent writes, from the Dove Marine Laboratory, Cuttercoats, England, that, at Hindon, a suburb of Sunderland, Aug. 24, 1918, hundreds of small fishes, identified as sand eels, had fallen—

Again the small area: about 60 by 30 yards.

The fall occurred during a heavy rain that was accompanied by thunder—or indications of disturbance aloft—but by no visible lightning. The sea is close to Hindon, but if you try to think of these fishes having described a trajectory in a whirlwind from the ocean, consider this remarkable datum:

That, according to witnesses, the fall upon this small area occupied ten minutes.

I cannot think of a clearer indication of a direct fall from a stationary source.

And:

"The fish were all dead, and indeed stiff and hard, when picked up, immediately after the occurrence."

By all of which I mean that we have only begun to pile up our data of things that fall from a stationary source overhead: we'll have to take up the subject from many approaches before our acceptance, which seems quite as rigorously arrived at as ever has been a belief, can emerge from the accursed.

I don't know how much the horse and the barn will help us to emerge: but, if ever anything did go up from this earth's surface and stay up—those damned things may have:

Monthly Weather Review, May, 1878:

In a tornado, in Wisconsin, May 23, 1878, "a barn and a horse were carried completely away, and neither horse nor barn, nor any portion of either have since been found."

After that, which would be a little strong were it not for a steady improvement in our digestions that I note as we go along, there is little of the bizarre or the unassimilable in the turtle that hovered six months or so over a small town in Mississippi:

Monthly Weather Review, May, 1894:

That, May 11, 1894, at Vicksburg, Miss., fell a small piece of alabaster; that, at Bovina, eight miles from Vicksburg, fell a gopher turtle.

They fell in a hailstorm.

This item was widely copied at the time: for instance, Nature, one of the volumes of 1894, page 430, and Jour. Roy. Met. Soc., 20-273. As to discussion—not a word. Or Science and its continuity with Presbyterianism—data like this are damned at birth. The Weather Review does sprinkle, or baptize, or attempt to save, this infant—but in all the meteorological literature that I have gone through, after that date—not a word, except mention once or twice. The Editor of the Review says:

"An examination of the weather map shows that these hailstorms occur on the south side of a region of cold northerly winds, and were but a small part of a series of similar storms; apparently some special local whirls or gusts carried heavy objects from this earth's surface up to the cloud regions."

Of all incredibilities that we have to choose from, I give first place to a notion of a whirlwind pouncing upon a region and scrupulously selecting a turtle and a piece of alabaster. This time, the other mechanical thing "there in the first place" cannot rise in response to its stimulus: it is resisted in that these objects were coated with ice—month of May in a southern state. If a whirlwind at all, there must have been very limited selection: there is no record of the fall of other objects. But there is no attempt in the Review to specify a whirlwind.

These strangely associated things were remarkably separated.

They fell eight miles apart.

Then—as if there were real reasoning—they must have been high to fall with such divergence, or one of them must have been carried partly horizontally eight miles farther than the other. But either supposition argues for power more than that of a local whirl or gust, or argues for a great, specific disturbance, of which there is no record—for the month of May, 1894.

Nevertheless—as if I really were reasonable—I do feel that I have to accept that this turtle had been raised from this earth's surface, somewhere near Vicksburg—because the gopher turtle is common in the southern states.

Then I think of a hurricane that occurred in the state of Mississippi weeks or months before May 11, 1894.

No—I don't look for it—and inevitably find it.

Or that things can go up so high in hurricanes that they stay up indefinitely—but may, after a while, be shaken down by storms. Over and over have we noted the occurrence of strange falls in storms. So then that the turtle and the piece of alabaster may have had far different origins—from different worlds, perhaps—have entered a region of suspension over this earth—wafting near each other—long duration—final precipitation by atmospheric disturbance—with hail—or that hailstones, too, when large, are phenomena of suspension of long duration: that it is highly unacceptable that the very large ones could become so great only in falling from the clouds.

Over and over has the note of disagreeableness, or of putrefaction, been struck—long duration. Other indications of long duration.

I think of a region somewhere above this earth's surface in which gravitation is inoperative and is not governed by the square of the distance—quite as magnetism is negligible at a very short distance from a magnet. Theoretically the attraction of a magnet should decrease with the square of the distance, but the falling-off is found to be almost abrupt at a short distance.

I think that things raised from this earth's surface to that region have been held there until shaken down by storms—

The Super-Sargasso Sea.

Derelicts, rubbish, old cargoes from inter-planetary wrecks; things cast out into what is called space by convulsions of other planets, things from the times of the Alexanders, Caesars and Napoleons of Mars and Jupiter and Neptune; things raised by this earth's cyclones: horses and barns and elephants and flies and dodoes, moas, and pterodactyls; leaves from modern trees and leaves of the Carboniferous era—all, however, tending to disintegrate into homogeneous-looking muds or dusts, red or black or yellow—treasure-troves for the palaeontologists and for the archaeologists—accumulations of centuries—cyclones of Egypt, Greece, and Assyria—fishes dried and hard, there a short time: others there long enough to putrefy—

But the omnipresence of Heterogeneity—or living fishes, also—ponds of fresh water: oceans of salt water.

As to the Law of Gravitation, I prefer to take one simple stand:

Orthodoxy accepts the correlation and equivalence of forces:

Gravitation is one of these forces.

All other forces have phenomena of repulsion and of inertness irrespective of distance, as well as of attraction.

But Newtonian Gravitation admits attraction only:

Then Newtonian Gravitation can be only one-third acceptable even to the orthodox, or there is denial of the correlation and equivalence of forces.

Or still simpler:

Here are the data.

Make what you will, yourself, of them.

In our Intermediatist revolt against homogeneous, or positive, explanations, or our acceptance that the all-sufficing cannot be less than universality, besides which, however, there would be nothing to suffice, our expression upon the Super-Sargasso Sea, though it harmonizes with data of fishes that fall as if from a stationary source—and, of course, with other data, too—is inadequate to account for two peculiarities of the falls of frogs:

That never has a fall of tadpoles been reported;

That never has a fall of full-grown frogs been reported—

Always frogs a few months old.

It sounds positive, but if there be such reports they are somewhere out of my range of reading.

But tadpoles would be more likely to fall from the sky than would frogs, little or big, if such falls be attributed to whirlwinds; and more likely to fall from the Super-Sargasso Sea if, though very tentatively and provisionally, we accept the Super-Sargasso Sea.

Before we take up an especial expression upon the

Comments (0)