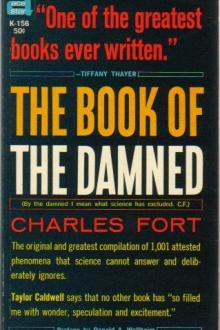

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

In my own tendency to exclude, or in the attitude of one peasant or savage who thinks he is not to be classed with other peasants or savages, I am not very much impressed with what natives think. It would be hard to tell why. If the word of a Lord Kelvin carries no more weight, upon scientific subjects, than the word of a Sitting Bull, unless it be in agreement with conventional opinion—I think it must be because savages have bad table manners. However, my snobbishness, in this respect, loosens up somewhat before very widespread belief by savages and peasants. And the notion of "thunderstones" is as wide as geography itself.

The natives of Burma, China, Japan, according to Blinkenberg (Thunder Weapons, p. 100)—not, of course, that Blinkenberg accepts one word of it—think that carved stone objects have fallen from the sky, because they think they have seen such objects fall from the sky. Such objects are called "thunderbolts" in these countries. They are called "thunderstones" in Moravia, Holland, Belgium, France, Cambodia, Sumatra, and Siberia. They're called "storm stones" in Lausitz; "sky arrows" in Slavonia; "thunder axes" in England and Scotland; "lightning stones" in Spain and Portugal; "sky axes" in Greece; "lightning flashes" in Brazil; "thunder teeth" in Amboina.

The belief is as widespread as is belief in ghosts and witches, which only the superstitious deny today.

As to beliefs by North American Indians, Tyler gives a list of references (Primitive Culture, 2-237). As to South American Indians—"Certain stone hatchets are said to have fallen from the heavens." (Jour. Amer. Folk Lore, 17-203.)

If you, too, revolt against coincidence after coincidence after coincidence, but find our interpretation of "thunderstones" just a little too strong or rich for digestion, we recommend the explanation of one, Tallius, written in 1649:

"The naturalists say they are generated in the sky by fulgurous exhalation conglobed in a cloud by the circumfused humor."

Of course the paper in the Cornhill Magazine was written with no intention of trying really to investigate this subject, but to deride the notion that worked-stone objects have ever fallen from the sky. A writer in the Amer. Jour. Sci., 1-21-325, read this paper and thinks it remarkable "that any man of ordinary reasoning powers should write a paper to prove that thunderbolts do not exist."

I confess that we're a little flattered by that.

Over and over:

"It is scarcely necessary to suggest to the intelligent reader that thunderstones are a myth."

We contend that there is a misuse of a word here: we admit that only we are intelligent upon this subject, if by intelligence is meant the inquiry of inequilibrium, and that all other intellection is only mechanical reflex—of course that intelligence, too, is mechanical, but less orderly and confined: less obviously mechanical—that as an acceptance of ours becomes firmer and firmer-established, we pass from the state of intelligence to reflexes in ruts. An odd thing is that intelligence is usually supposed to be creditable. It may be in the sense that it is mental activity trying to find out, but it is confession of ignorance. The bees, the theologians, the dogmatic scientists are the intellectual aristocrats. The rest of us are plebeians, not yet graduated to Nirvana, or to the instinctive and suave as differentiated from the intelligent and crude.

Blinkenberg gives many instances of the superstition of "thunderstones" which flourishes only where mentality is in a lamentable state—or universally. In Malacca, Sumatra, and Java, natives say that stone axes have often been found under trees that have been struck by lightning. Blinkenberg does not dispute this, but says it is coincidence: that the axes were of course upon the ground in the first place: that the natives jumped to the conclusion that these carved stones had fallen in or with lightning. In Central Africa, it is said that often have wedge-shaped, highly polished objects of stone, described as "axes," been found sticking in trees that have been struck by lightning—or by what seemed to be lightning. The natives, rather like the unscientific persons of Memphis, Tenn., when they saw snakes after a storm, jumped to the conclusion that the "axes" had not always been sticking in the trees. Livingstone (Last Journal, pages 83, 89, 442, 448) says that he had never heard of stone implements used by natives of Africa. A writer in the Report of the Smithsonian Institution, 1877-308, says that there are a few.

That they are said, by the natives, to have fallen in thunderstorms.

As to luminosity, it is my lamentable acceptance that bodies falling through this earth's atmosphere, if not warmed even, often fall with a brilliant light, looking like flashes of lightning. This matter seems important: we'll take it up later, with data. In Prussia, two stone axes were found in the trunks of trees, one under the bark. (Blinkenberg, Thunder Weapons, p. 100.)

The finders jumped to the conclusion that the axes had fallen there.

Another stone ax—or wedge-shaped object of worked stone—said to have been found in a tree that had been struck by something that looked like lightning. (Thunder Weapons, p. 71.)

The finder jumped to the conclusion.

Story told by Blinkenberg, of a woman, who lived near Kulsbjaergene, Sweden, who found a flint near an old willow—"near her house." I emphasize "near her house" because that means familiar ground. The willow had been split by something.

She jumped.

Cow killed by lightning, or by what looked like lightning (Isle of Sark, near Guernsey). The peasant who owned the cow dug up the ground at the spot and found a small greenstone "ax." Blinkenberg says that he jumped to the conclusion that it was this object that had fallen luminously, killing the cow.

Reliquary, 1867-208:

A flint ax found by a farmer, after a severe storm—described as a "fearful storm"—by a signal staff, which had been split by something. I should say that nearness to a signal staff may be considered familiar ground.

Whether he jumped, or arrived at the conclusion by a more leisurely process, the farmer thought that the flint object had fallen in the storm.

In this instance we have a lamentable scientist with us. It's impossible to have positive difference between orthodoxy and heresy: somewhere there must be a merging into each other, or an overlapping. Nevertheless, upon such a subject as this, it does seem a little shocking. In most works upon meteorites, the peculiar, sulphurous odor of things that fall from the sky is mentioned. Sir John Evans (Stone Implements, p. 57) says—with extraordinary reasoning powers, if he could never have thought such a thing with ordinary reasoning powers—that this flint object "proved to have been the bolt, by its peculiar smell when broken."

If it did so prove to be, that settles the whole subject. If we prove that only one object of worked stone has fallen from the sky, all piling up of further reports is unnecessary. However, we have already taken the stand that nothing settles anything; that the disputes of ancient Greece are no nearer solution now than they were several thousand years ago—all because, in a positive sense, there is nothing to prove or solve or settle. Our object is to be more nearly real than our opponents. Wideness is an aspect of the Universal. We go on widely. According to us the fat man is nearer godliness than is the thin man. Eat, drink, and approximate to the Positive Absolute. Beware of negativeness, by which we mean indigestion.

The vast majority of "thunderstones" are described as "axes," but Meunier (La Nature, 1892-2-381) tells of one that was in his possession; said to have fallen at Ghardia, Algeria, contrasting "profoundment" (pear-shaped) with the angular outlines of ordinary meteorites. The conventional explanation that it had been formed as a drop of molten matter from a larger body seems reasonable to me; but with less agreeableness I note its fall in a thunderstorm, the datum that turns the orthodox meteorologist pale with rage, or induces a slight elevation of his eyebrows, if you mention it to him.

Meunier tells of another "thunderstone" said to have fallen in North Africa. Meunier, too, is a little lamentable here: he quotes a soldier of experience that such objects fall most frequently in the deserts of Africa.

Rather miscellaneous now:

"Thunderstone" said to have fallen in London, April, 1876: weight about 8 pounds: no particulars as to shape (Timb's Year Book, 1877-246).

"Thunderstone" said to have fallen at Cardiff, Sept. 26, 1916 (London Times, Sept. 28, 1916). According to Nature, 98-95, it was coincidence; only a lightning flash had been seen.

Stone that fell in a storm, near St. Albans, England: accepted by the Museum of St. Albans; said, at the British Museum, not to be of "true meteoritic material." (Nature, 80-34.)

London Times, April 26, 1876:

That, April 20, 1876, near Wolverhampton, fell a mass of meteoritic iron during a heavy fall of rain. An account of this phenomenon in Nature, 14-272, by H.S. Maskelyne, who accepts it as authentic. Also, see Nature, 13-531.

For three other instances, see the Scientific American, 47-194; 52-83; 68-325.

As to wedge-shape larger than could very well be called an "ax":

Nature, 30-300:

That, May 27, 1884, at Tysnas, Norway, a meteorite had fallen: that the turf was torn up at the spot where the object had been supposed to have fallen; that two days later "a very peculiar stone" was found near by. The description is—"in shape and size very like the fourth part of a large Stilton cheese."

It is our acceptance that many objects and different substances have been brought down by atmospheric disturbance from what—only as a matter of convenience now, and until we have more data—we call the Super-Sargasso Sea; however, our chief interest is in objects that have been shaped by means similar to human handicraft.

Description of the "thunderstones" of Burma (Proc. Asiatic Soc. of Bengal, 1869-183): said to be of a kind of stone unlike any other found in Burma; called "thunderbolts" by the natives. I think there's a good deal of meaning in such expressions as "unlike any other found in Burma"—but that if they had said anything more definite, there would have been unpleasant consequences to writers in the 19th century.

More about the "thunderstones" of Burma, in the Proc. Soc. Antiq. of London, 2-3-97. One of them, described as an "adze," was exhibited by Captain Duff, who wrote that there was no stone like it in its neighborhood.

Of course it may not be very convincing to say that because a stone is unlike neighboring stones it had foreign origin—also we fear it is a kind of plagiarism: we got it from the geologists, who demonstrate by this reasoning the foreign origin of erratics. We fear we're a little gross and scientific at times.

But it's my acceptance that a great deal of scientific literature must be read between the lines. It's not everyone who has the lamentableness of a Sir John Evans. Just as a great deal of Voltaire's meaning was inter-linear, we suspect that a Captain Duff merely hints rather than to risk having a Prof. Lawrence Smith fly at him and call him "a half-insane man." Whatever Captain Duff's meaning may have been, and whether he smiled like a Voltaire when he wrote it, Captain Duff writes of "the extremely soft nature of the stone, rendering it equally useless as an offensive or defensive weapon."

Story, by a correspondent, in Nature, 34-53, of a Malay, of "considerable social standing"—and one thing about our data is that, damned though they be, they do so often bring us into awful good company—who knew of a tree that had been struck, about a month before, by something in a thunderstorm. He searched among the roots of this tree and found a "thunderstone." Not said whether he jumped or leaped to the conclusion that it had fallen: process likely to be

Comments (0)