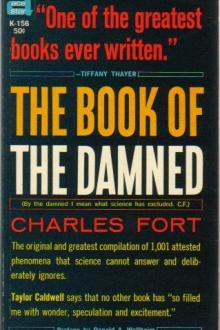

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

If he thinks of a long translation—all the way from the south of France to Upper Savoy, he may think then of a very fine sorting over by differences of specific gravity—but in such a fine selection, larvae would be separated from developed insects.

As to differences in specific gravity—the yellow larvae that fell in Switzerland January, 1890, were three times the size of the black larvae that fell with them. In accounts of this occurrence, there is no denial of the fall.

Or that a whirlwind never brought them together and held them together and precipitated them and only them together—

That they came from Genesistrine.

There's no escape from it. We'll be persecuted for it. Take it or leave it—

Genesistrine.

The notion is that there is somewhere aloft a place of origin of life relatively to this earth. Whether it's the planet Genesistrine, or the moon, or a vast amorphous region super-jacent to this earth, or an island in the Super-Sargasso Sea, should perhaps be left to the researches of other super—or extra—geographers. That the first unicellular organisms may have come here from Genesistrine—or that men or anthropomorphic beings may have come here before amoebae: that, upon Genesistrine, there may have been an evolution expressible in conventional biologic terms, but that evolution upon this earth has been—like evolution in modern Japan—induced by external influences; that evolution, as a whole, upon this earth, has been a process of population by immigration or by bombardment. Some notes I have upon remains of men and animals encysted, or covered with clay or stone, as if fired here as projectiles, I omit now, because it seems best to regard the whole phenomenon as a tropism—as a geotropism—probably atavistic, or vestigial, as it were, or something still continuing long after expiration of necessity; that, once upon a time, all kinds of things came here from Genesistrine, but that now only a few kinds of bugs and things, at long intervals, feel the inspiration.

Not one instance have we of tadpoles that have fallen to this earth. It seems reasonable that a whirlwind could scoop up a pond, frogs and all, and cast down the frogs somewhere else: but, then, more reasonable that a whirlwind could scoop up a pond, tadpoles and all—because tadpoles are more numerous in their season than are the frogs in theirs: but the tadpole-season is earlier in the spring, or in a time that is more tempestuous. Thinking in terms of causation—as if there were real causes—our notion is that, if X is likely to cause Y, but is more likely to cause Z, but does not cause Z, X is not the cause of Y. Upon this quasi-sorites, we base our acceptance that the little frogs that have fallen to this earth are not products of whirlwinds: that they came from externality, or from Genesistrine.

I think of Genesistrine in terms of biologic mechanics: not that somewhere there are persons who collect bugs in or about the last of January and frogs in July and August, and bombard this earth, any more than do persons go through northern regions, catching and collecting birds, every autumn, then casting them southward.

But atavistic, or vestigial, geotropism in Genesistrine—or a million larvae start crawling, and a million little frogs start hopping—knowing no more what it's all about than we do when we crawl to work in the morning and hop away at night.

I should say, myself, that Genesistrine is a region in the Super-Sargasso Sea, and that parts of the Super-Sargasso Sea have rhythms of susceptibility to this earth's attraction.

8I accept that, when there are storms, the damnedest of excluded, excommunicated things—things that are leprous to the faithful—are brought down—from the Super-Sargasso Sea—or from what for convenience we call the Super-Sargasso Sea—which by no means has been taken into full acceptance yet.

That things are brought down by storms, just as, from the depths of the sea things are brought up by storms. To be sure it is orthodoxy that storms have little, if any, effect below the waves of the ocean—but—of course—only to have an opinion is to be ignorant of, or to disregard a contradiction, or something else that modifies an opinion out of distinguishability.

Symons' Meteorological Magazine, 47-180:

That, along the coast of New Zealand, in regions not subject to submarine volcanic action, deep-sea fishes are often brought up by storms.

Iron and stones that fall from the sky; and atmospheric disturbances:

"There is absolutely no connection between the two phenomena." (Symons.)

The orthodox belief is that objects moving at planetary velocity would, upon entering this earth's atmosphere, be virtually unaffected by hurricanes; might as well think of a bullet swerved by someone fanning himself. The only trouble with the orthodox reasoning is the usual trouble—its phantom-dominant—its basing upon a myth—data we've had, and more we'll have, of things in the sky having no independent velocity.

There are so many storms and so many meteors and meteorites that it would be extraordinary if there were no concurrences. Nevertheless so many of these concurrences are listed by Prof. Baden-Powell (Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1850-54) that one—notices.

See Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1860—other instances.

The famous fall of stones at Siena, Italy, 1794—"in a violent storm."

See Greg's Catalogues—many instances. One that stands out is—"bright ball of fire and light in a hurricane in England, Sept. 2, 1786." The remarkable datum here is that this phenomenon was visible forty minutes. That's about 800 times the duration that the orthodox give to meteors and meteorites.

See the Annual Register—many instances.

In Nature, Oct. 25, 1877, and the London Times, Oct. 15, 1877, something that fell in a gale of Oct. 14, 1877, is described as a "huge ball of green fire." This phenomenon is described by another correspondent, in Nature, 17-10, and an account of it by another correspondent was forwarded to Nature by W.F. Denning.

There are so many instances that some of us will revolt against the insistence of the faithful that it is only coincidence, and accept that there is connection of the kind called causal. If it is too difficult to think of stones and metallic masses swerved from their courses by storms, if they move at high velocity, we think of low velocity, or of things having no velocity at all, hovering a few miles above this earth, dislodged by storms, and falling luminously.

But the resistance is so great here, and "coincidence" so insisted upon that we'd better have some more instances:

Aerolite in a storm at St. Leonards-on-sea, England, Sept. 17, 1885—no trace of it found (Annual Register, 1885); meteorite in a gale, March 1, 1886, described in the Monthly Weather Review, March, 1886; meteorite in a thunderstorm, off coast of Greece, Nov. 19, 1899 (Nature, 61-111); fall of a meteorite in a storm, July 7, 1883, near Lachine, Quebec (Monthly Weather Review, July, 1883); same phenomenon noted in Nature, 28-319; meteorite in a whirlwind, Sweden, Sept. 24, 1883 (Nature, 29-15).

London Roy. Soc. Proc., 6-276:

A triangular cloud that appeared in a storm, Dec. 17, 1852; a red nucleus, about half the apparent diameter of the moon, and a long tail; visible 13 minutes; explosion of the nucleus.

Nevertheless, in Science Gossip, n.s., 6-65, it is said that, though meteorites have fallen in storms, no connection is supposed to exist between the two phenomena, except by the ignorant peasantry.

But some of us peasants have gone through the Report of the British Association, 1852. Upon page 239, Dr. Buist, who had never heard of the Super-Sargasso Sea, says that, though it is difficult to trace connection between the phenomena, three aerolites had fallen in five months, in India, during thunderstorms, in 1851 (may have been 1852). For accounts by witnesses, see page 229 of the Report.

Or—we are on our way to account for "thunderstones."

It seems to me that, very strikingly here, is borne out the general acceptance that ours is only an intermediate existence, in which there is nothing fundamental, or nothing final to take as a positive standard to judge by.

Peasants believed in meteorites.

Scientists excluded meteorites.

Peasants believe in "thunderstones."

Scientists exclude "thunderstones."

It is useless to argue that peasants are out in the fields, and that scientists are shut up in laboratories and lecture rooms. We cannot take for a real base that, as to phenomena with which they are more familiar, peasants are more likely to be right than are scientists: a host of biologic and meteorologic fallacies of peasants rises against us.

I should say that our "existence" is like a bridge—except that that comparison is in static terms—but like the Brooklyn Bridge, upon which multitudes of bugs are seeking a fundamental—coming to a girder that seems firm and final—but the girder is built upon supports. A support then seems final. But it is built upon underlying structures. Nothing final can be found in all the bridge, because the bridge itself is not a final thing in itself, but is a relationship between Manhattan and Brooklyn. If our "existence" is a relationship between the Positive Absolute and the Negative Absolute, the quest for finality in it is hopeless: everything in it must be relative, if the "whole" is not a whole, but is, itself, a relation.

In the attitude of Acceptance, our pseudo-base is:

Cells of an embryo are in the reptilian era of the embryo;

Some cells feel stimuli to take on new appearances.

If it be of the design of the whole that the next era be mammalian, those cells that turn mammalian will be sustained against resistance, by inertia, of all the rest, and will be relatively right, though not finally right, because they, too, in time will have to give way to characters of other eras of higher development.

If we are upon the verge of a new era, in which Exclusionism must be overthrown, it will avail thee not to call us base-born and frowsy peasants.

In our crude, bucolic way, we now offer an outrage upon common sense that we think will some day be an unquestioned commonplace:

That manufactured objects of stone and iron have fallen from the sky:

That they have been brought down from a state of suspension, in a region of inertness to this earth's attraction, by atmospheric disturbances.

The "thunderstone" is usually "a beautifully polished, wedge-shaped piece of greenstone," says a writer in the Cornhill Magazine, 50-517. It isn't: it's likely to be of almost any kind of stone, but we call attention to the skill with which some of them have been made. Of course this writer says it's all superstition. Otherwise he'd be one of us crude and simple sons of the soil.

Conventional damnation is that stone implements, already on the ground—"on the ground in the first place"—are found near where lightning was seen to strike: that are supposed by astonished rustics, or by intelligence of a low order, to have fallen in or with lightning.

Throughout this book, we class a great deal of science with bad fiction. When is fiction bad, cheap, low? If coincidence is overworked. That's one way of deciding. But with single writers coincidence seldom is overworked: we find the excess in the subject at large. Such a writer as the one of the Cornhill Magazine tells us vaguely of beliefs of peasants: there is no massing of instance after instance after instance. Here ours will be the method of mass-formation.

Conceivably lightning may strike the ground near where there was a wedge-shaped object in the first place: again and again and again: lightning striking ground near wedge-shaped object in China; lightning striking ground near wedge-shaped object in Scotland; lightning striking ground near wedge-shaped object in Central Africa: coincidence in France; coincidence in Java; coincidence in South America—

We grant a great deal but note a tendency to restlessness. Nevertheless this is the psycho-tropism of science to all "thunderstones" said to have fallen luminously.

As to greenstone, it is in the island of Jamaica, where the notion is general that

Comments (0)