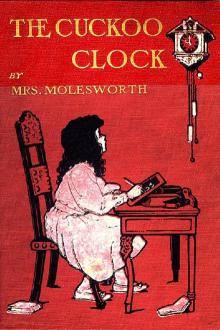

The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗

- Author: Mrs. Molesworth

- Performer: -

Book online «The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗». Author Mrs. Molesworth

"Have you heard what has happened, little missie?" said the old servant.

"Yes," replied Griselda.

"My ladies are in great trouble," continued Dorcas, who seemed inclined to be more communicative than usual, "and no wonder. For fifty years that clock has never gone wrong."

"Can't it be put right?" asked the child.

Dorcas shook her head.

"No good would come of interfering," she said. "What must be, must be. The luck of the house hangs on that clock. Its maker spent a good part of his life over it, and his last words were that it would bring good luck to the house that owned it, but that trouble would follow its silence. It's my belief," she added solemnly, "that it's a fairy clock, neither more nor less, for good luck it has brought there's no denying. There are no cows like ours, missie—their milk is a proverb hereabouts; there are no hens like ours for laying all the year round; there are no roses like ours. And there's always a friendly feeling in this house, and always has been. 'Tis not a house for wrangling and jangling, and sharp words. The 'good people' can't stand that. Nothing drives them away like ill-temper or anger."

Griselda's conscience gave her a sharp prick. Could it be her doing that trouble was coming upon the old house? What a punishment for a moment's fit of ill-temper.

"I wish you wouldn't talk that way, Dorcas," she said; "it makes me so unhappy."

"What a feeling heart the child has!" said the old servant as she went on her way downstairs. "It's true—she is very like Miss Sybilla."

That day was a very weary and sad one for Griselda. She was oppressed by a feeling she did not understand. She knew she had done wrong, but she had sorely repented it, and "I do think the cuckoo might have come back again," she said to herself, "if he is a fairy; and if he isn't, it can't be true what Dorcas says."

Her aunts made no allusion to the subject in her presence, and almost seemed to have forgotten that she had known of their distress. They were more grave and silent than usual, but otherwise things went on in their ordinary way. Griselda spent the morning "at her tasks," in the ante-room, but was thankful to get away from the tick-tick of the clock in the corner and out into the garden.

But there, alas! it was just as bad. The rooks seemed to know that something was the matter; they set to work making such a chatter immediately Griselda appeared that she felt inclined to run back into the house again.

"I am sure they are talking about me," she said to herself. "Perhaps they are fairies too. I am beginning to think I don't like fairies."

She was glad when bed-time came. It was a sort of reproach to her to see her aunts so pale and troubled; and though she tried to persuade herself that she thought them very silly, she could not throw off the uncomfortable feeling.

She was so tired when she went to bed—tired in the disagreeable way that comes from a listless, uneasy day—that she fell asleep at once and slept heavily. When she woke, which she did suddenly, and with a start, it was still perfectly dark, like the first morning that she had wakened in the old house. It seemed to her that she had not wakened of herself—something had roused her. Yes! there it was again, a very, very soft distant "cuckoo." Was it distant? She could not tell. Almost she could have fancied it was close to her.

"If it's that cuckoo come back again, I'll catch him!" exclaimed Griselda.

She darted out of bed, felt her way to the door, which was closed, and opening it let in a rush of moonlight from the unshuttered passage window. In another moment her little bare feet were pattering along the passage at full speed, in the direction of the great saloon.

For Griselda's childhood among the troop of noisy brothers had taught her one lesson—she was afraid of nothing. Or rather perhaps I should say she had never learnt that there was anything to be afraid of! And is there?

OBEYING ORDERS

If we're to take kindly to ours:

Then pull up the weeds with a will,

And fairies will cherish the flowers."

here was moonlight, though not so much, in the saloon and the ante-room, too; for though the windows, like those in Griselda's bed-room, had the shutters closed, there was a round part at the top, high up, which the shutters did not reach to, and in crept, through these clear uncovered panes, quite as many moonbeams, you may be sure, as could find their way.

Griselda, eager though she was, could not help standing still a moment to admire the effect.

"It looks prettier with the light coming in at those holes at the top than even if the shutters were open," she said to herself. "How goldy-silvery the cabinet looks; and, yes, I do declare, the mandarins are nodding! I wonder if it is out of politeness to me, or does Aunt Grizzel come in last thing at night and touch them to make them keep nodding till morning? I suppose they're a sort of policemen to the palace; and I dare say there are all sorts of beautiful things inside. How I should like to see all through it!"

But at this moment the faint tick-tick of the cuckoo clock in the next room, reaching her ear, reminded her of the object of this midnight expedition of hers. She hurried into the ante-room.

It looked darker than the great saloon, for it had but one window. But through the uncovered space at the top of this window there penetrated some brilliant moonbeams, one of which lighted up brightly the face of the clock with its queer over-hanging eaves.

Griselda approached it and stood below, looking up.

"Cuckoo," she said softly—very softly.

But there was no reply.

"Cuckoo," she repeated rather more loudly. "Why won't you speak to me? I know you are there, and you're not asleep, for I heard your voice in my own room. Why won't you come out, cuckoo?"

"Tick-tick," said the clock, but there was no other reply.

Griselda felt ready to cry.

"Cuckoo," she said reproachfully, "I didn't think you were so hard-hearted. I have been so unhappy about you, and I was so pleased to hear your voice again, for I thought I had killed you, or hurt you very badly; and I didn't mean to hurt you, cuckoo. I was sorry the moment I had done it, dreadfully sorry. Dear cuckoo, won't you forgive me?"

she could not help very softly clapping her hands

There was a little sound at last—a faint coming sound, and by the moonlight Griselda saw the doors open, and out flew the cuckoo. He stood still for a moment, looked round him as it were, then gently flapped his wings, and uttered his usual note—"Cuckoo."

Griselda stood in breathless expectation, but in her delight she could not help very softly clapping her hands.

The cuckoo cleared his throat. You never heard such a funny little noise as he made; and then, in a very clear, distinct, but yet "cuckoo-y" voice, he spoke.

"Griselda," he said, "are you truly sorry?"

"I told you I was," she replied. "But I didn't feel so very naughty, cuckoo. I didn't, really. I was only vexed for one minute, and when I threw the book I seemed to be a very little in fun, too. And it made me so unhappy when you went away, and my poor aunts have been dreadfully unhappy too. If you hadn't come back I should have told them tomorrow what I had done. I would have told them before, but I was afraid it would have made them more unhappy. I thought I had hurt you dreadfully."

"So you did," said the cuckoo.

"But you look quite well," said Griselda.

"It was my feelings," replied the cuckoo; "and I couldn't help going away. I have to obey orders like other people."

Griselda stared. "How do you mean?" she asked.

"Never mind. You can't understand at present," said the cuckoo. "You can understand about obeying your orders, and you see, when you don't, things go wrong."

"Yes," said Griselda humbly, "they certainly do. But, cuckoo," she continued, "I never used to get into tempers at home—hardly never, at least; and I liked my lessons then, and I never was scolded about them."

"What's wrong here, then?" said the cuckoo. "It isn't often that things go wrong in this house."

"That's what Dorcas says," said Griselda. "It must be with my being a child—my aunts and the house and everything have got out of children's ways,"

"About time they did," remarked the cuckoo drily.

"And so," continued Griselda, "it is really very dull. I have lots of lessons, but it isn't so much that I mind. It is that I've no one to play with."

"There's something in that," said the cuckoo. He flapped his wings and was silent for a minute or two. "I'll consider about it," he observed at last.

"Thank you," said Griselda, not exactly knowing what else to say.

"And in the meantime," continued the cuckoo, "you'd better obey present orders and go back to bed."

"Shall I say good-night to you, then?" asked Griselda somewhat timidly.

"You're quite welcome to do so," replied the cuckoo. "Why shouldn't you?"

"You see I wasn't sure if you would like it," returned Griselda, "for of course you're not like a person, and—and—I've been told all sorts of queer things about what fairies like and don't like."

"Who said I was a fairy?" inquired the cuckoo.

"Dorcas did, and, of course, my own common sense did too," replied Griselda. "You must be a fairy—you couldn't be anything else."

"I might be a fairyfied cuckoo," suggested the bird.

Griselda looked puzzled.

"I don't understand," she said, "and I don't think it could make much difference. But whatever you are, I wish you would tell me one thing."

"What?" said the cuckoo.

"I want to know, now that you've forgiven me for throwing the book at you, have you come back for good?"

"Certainly not for evil," replied the cuckoo.

Griselda gave a little wriggle. "Cuckoo, you're laughing at me," she said. "I mean, have you come back to stay and cuckoo as usual and make my aunts happy again?"

"You'll see in the morning," said the cuckoo. "Now go off to bed."

"Good night," said Griselda, "and thank you, and please don't forget to let me know when you've considered."

"Cuckoo, cuckoo," was her little friend's reply. Griselda thought it was meant for good night, but the fact of the matter was that at that exact second of time it was two o'clock in the morning.

She made her way back to bed. She had been standing some time talking to the cuckoo, but, though it was now well on in November, she did not feel the least cold, nor sleepy! She felt as happy and light-hearted as possible, and she wished it was morning, that she might get up. Yet the moment she laid her little brown curly head on the pillow, she fell asleep; and it seemed to her that just as she dropped off

Comments (0)