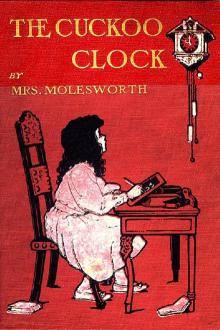

The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗

- Author: Mrs. Molesworth

- Performer: -

Book online «The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗». Author Mrs. Molesworth

"It was your own fault. You wouldn't get ready," said the cuckoo, "Now, here goes! Flap and wish."

Griselda flapped and wished. She felt a sort of rustle in the air, that was all—then she found herself standing with the cuckoo in front of the Chinese cabinet, the door of which stood open, while the mandarins on each side, nodding politely, seemed to invite them to enter. Griselda hesitated.

"Go on," said the cuckoo, patronizingly; "ladies first."

Griselda went on. To her surprise, inside the cabinet it was quite light, though where the light came from that illuminated all the queer corners and recesses and streamed out to the front, where stood the mandarins, she could not discover.

The "palace" was not quite as interesting as she had expected. There were lots of little rooms in it opening on to balconies commanding, no doubt, a splendid view of the great saloon; there were ever so many little stair-cases leading to more little rooms and balconies; but it all seemed empty and deserted.

"I don't care for it," said Griselda, stopping short at last; "it's all the same, and there's nothing to see. I thought my aunts kept ever so many beautiful things in here, and there's nothing."

"Come along, then," said the cuckoo. "I didn't expect you'd care for the palace, as you called it, much. Let us go out the other way."

He hopped down a sort of little staircase near which they were standing, and Griselda followed him willingly enough. At the foot they found themselves in a vestibule, much handsomer than the entrance at the other side, and the cuckoo, crossing it, lifted one of his claws and touched a spring in the wall. Instantly a pair of large doors flew open in the middle, revealing to Griselda the prettiest and most curious sight she had ever seen.

A flight of wide, shallow steps led down from this doorway into a long, long avenue bordered by stiffly growing trees, from the branches of which hung innumerable lamps of every colour, making a perfect network of brilliance as far as the eye could reach.

he flapped his wings, and a palanquin appeared at the foot of the steps

"Oh, how lovely!" cried Griselda, clapping her hands. "It'll be like walking along a rainbow. Cuckoo, come quick."

"Stop," said the cuckoo; "we've a good way to go. There's no need to walk. Palanquin!"

He flapped his wings, and instantly a palanquin appeared at the foot of the steps. It was made of carved ivory, and borne by four Chinese-looking figures with pigtails and bright-coloured jackets. A feeling came over Griselda that she was dreaming, or else that she had seen this palanquin before. She hesitated. Suddenly she gave a little jump of satisfaction.

"I know," she exclaimed. "It's exactly like the one that stands under a glass shade on Lady Lavander's drawing-room mantelpiece. I wonder if it is the very one? Fancy me being able to get into it!"

She looked at the four bearers. Instantly they all nodded.

"What do they mean?" asked Griselda, turning to the cuckoo.

"Get in," he replied.

"Yes, I'm just going to get in," she said; "but what do they mean when they nod at me like that?"

"They mean, of course, what I tell you—'Get in,'" said the cuckoo.

"Why don't they say so, then?" persisted Griselda, getting in, however, as she spoke.

"Griselda, you have a very great——" began the cuckoo, but Griselda interrupted him.

"Cuckoo," she exclaimed, "if you say that again, I'll jump out of the palanquin and run away home to bed. Of course I've a great deal to learn—that's why I like to ask questions about everything I see. Now, tell me where we are going."

"In the first place," said the cuckoo, "are you comfortable?"

"Very," said Griselda, settling herself down among the cushions.

It was a change from the cuckoo's boudoir. There were no chairs or seats, only a number of very, very soft cushions covered with green silk. There were green silk curtains all round, too, which you could draw or not as you pleased, just by touching a spring. Griselda stroked the silk gently. It was not "fruzzley" silk, if you know what that means; it did not make you feel as if your nails wanted cutting, or as if all the rough places on your skin were being rubbed up the wrong way; its softness was like that of a rose or pansy petal.

"What nice silk!" said Griselda. "I'd like a dress of it. I never noticed that the palanquin was lined so nicely," she continued, "for I suppose it is the one from Lady Lavander's mantelpiece? There couldn't be two so exactly like each other."

The cuckoo gave a sort of whistle.

"What a goose you are, my dear!" he exclaimed. "Excuse me," he continued, seeing that Griselda looked rather offended; "I didn't mean to hurt your feelings, but you won't let me say the other thing, you know. The palanquin from Lady Lavander's! I should think not. You might as well mistake one of those horrible paper roses that Dorcas sticks in her vases for one of your aunt's Gloires de Dijon! The palanquin from Lady Lavander's—a clumsy human imitation not worth looking at!"

"I didn't know," said Griselda humbly. "Do they make such beautiful things in Mandarin Land?"

"Of course," said the cuckoo.

Griselda sat silent for a minute or two, but very soon she recovered her spirits.

"Will you please tell me where we are going?" she asked again.

"You'll see directly," said the cuckoo; "not that I mind telling you. There's to be a grand reception at one of the palaces to-night. I thought you'd like to assist at it. It'll give you some idea of what a palace is like. By-the-by, can you dance?"

"A little," replied Griselda.

"Ah, well, I dare say you will manage. I've ordered a court dress for you. It will be all ready when we get there."

"Thank you," said Griselda.

In a minute or two the palanquin stopped. The cuckoo got out, and Griselda followed him.

She found that they were at the entrance to a very much grander palace than the one in her aunt's saloon. The steps leading up to the door were very wide and shallow, and covered with a gold embroidered carpet, which looked as if it would be prickly to her bare feet, but which, on the contrary, when she trod upon it, felt softer than the softest moss. She could see very little besides the carpet, for at each side of the steps stood rows and rows of mandarins, all something like, but a great deal grander than, the pair outside her aunt's cabinet; and as the cuckoo hopped and Griselda walked up the staircase, they all, in turn, row by row, began solemnly to nod. It gave them the look of a field of very high grass, through which, any one passing, leaves for the moment a trail, till all the heads bob up again into their places.

"What do they mean?" whispered Griselda.

"It's a royal salute," said the cuckoo.

"A salute!" said Griselda. "I thought that meant kissing or guns."

"Hush!" said the cuckoo, for by this time they had arrived at the top of the staircase; "you must be dressed now."

Two mandariny-looking young ladies, with porcelain faces and three-cornered head-dresses, stepped forward and led Griselda into a small ante-room, where lay waiting for her the most magnificent dress you ever saw. But how do you think they dressed her? It was all by nodding. They nodded to the blue and silver embroidered jacket, and in a moment it had fitted itself on to her. They nodded to the splendid scarlet satin skirt, made very short in front and very long behind, and before Griselda knew where she was, it was adjusted quite correctly. They nodded to the head-dress, and the sashes, and the necklaces and bracelets, and forthwith they all arranged themselves. Last of all, they nodded to the dearest, sweetest little pair of high-heeled shoes imaginable—all silver, and blue, and gold, and scarlet, and everything mixed up together, only they were rather a stumpy shape about the toes and Griselda's bare feet were encased in them, and, to her surprise, quite comfortably so.

"They don't hurt me a bit," she said aloud; "yet they didn't look the least the shape of my foot."

But her attendants only nodded; and turning round, she saw the cuckoo waiting for her. He did not speak either, rather to her annoyance, but gravely led the way through one grand room after another to the grandest of all, where the entertainment was evidently just about to begin. And everywhere there were mandarins, rows and rows, who all set to work nodding as fast as Griselda appeared. She began to be rather tired of royal salutes, and was glad when, at last, in profound silence, the procession, consisting of the cuckoo and herself, and about half a dozen "mandarins," came to a halt before a kind of daïs, or raised seat, at the end of the hall.

Upon this daïs stood a chair—a throne of some kind, Griselda supposed it to be—and upon this was seated the grandest and gravest personage she had yet seen.

"Is he the king of the mandarins?" she whispered. But the cuckoo did not reply; and before she had time to repeat the question, the very grand and grave person got down from his seat, and coming towards her offered her his hand, at the same time nodding—first once, then two or three times together, then once again. Griselda seemed to know what he meant. He was asking her to dance.

"Thank you," she said. "I can't dance very well, but perhaps you won't mind,"

The king, if that was his title, took not the slightest notice of her reply, but nodded again—once, then two or three times together, then once alone, just as before. Griselda did not know what to do, when suddenly she felt something poking her head. It was the cuckoo—he had lifted his claw, and was tapping her head to make her nod. So she nodded—once, twice together, then once—that appeared to be enough. The king nodded once again; an invisible band suddenly struck up the loveliest music, and off they set to the places of honour reserved for them in the centre of the room, where all the mandarins were assembling.

What a dance that was! It began like a minuet and ended something like the haymakers. Griselda had not the least idea what the figures or steps were, but it did not matter. If she did not know, her shoes or something about her did; for she got on famously. The music was lovely—"so the mandarins can't be deaf, though they are dumb," thought Griselda, "which is one good thing about them." The king seemed to enjoy it as much as she did, though he never smiled or laughed; any one could have seen he liked it by the way he whirled and twirled himself about. And between the figures, when they stopped to rest for a little, Griselda got on very well too. There was no conversation, or rather, if there was, it

Comments (0)