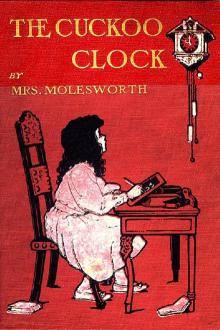

The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗

- Author: Mrs. Molesworth

- Performer: -

Book online «The Cuckoo Clock, Mrs. Molesworth [polar express read aloud .txt] 📗». Author Mrs. Molesworth

"Yesterday," corrected the cuckoo. "Always be exact in your statements, Griselda."

"Well, yesterday, then," said Griselda, rather tartly; "though when you know quite well what I mean, I don't see that you need be so very particular. Well, as I was saying, I tried and tried, but still they were fearful. They were, indeed."

"You've a great deal to learn, Griselda," repeated the cuckoo.

"I wish you wouldn't say that so often," said Griselda. "I thought you were going to play with me."

"There's something in that," said the cuckoo, "there's something in that. I should like to talk about it. But we could talk more comfortably if you would come up here and sit beside me."

Griselda thought her friend must be going out of his mind.

"Sit beside you up there!" she exclaimed. "Cuckoo, how could I? I'm far, far too big."

"Big!" returned the cuckoo. "What do you mean by big? It's all a matter of fancy. Don't you know that if the world and everything in it, counting yourself of course, was all made little enough to go into a walnut, you'd never find out the difference."

"Wouldn't I?" said Griselda, feeling rather muddled; "but, not counting myself, cuckoo, I would then, wouldn't I?"

"Nonsense," said the cuckoo hastily; "you've a great deal to learn, and one thing is, not to argue. Nobody should argue; it's a shocking bad habit, and ruins the digestion. Come up here and sit beside me comfortably. Catch hold of the chain; you'll find you can manage if you try."

"But it'll stop the clock," said Griselda. "Aunt Grizzel said I was never to touch the weights or the chains."

"Stuff," said the cuckoo; "it won't stop the clock. Catch hold of the chains and swing yourself up. There now—I told you you could manage it."

IVTHE COUNTRY OF THE NODDING MANDARINS

ow she managed it she never knew; but, somehow or other, it was managed. She seemed to slide up the chain just as easily as in a general way she would have slidden down, only without any disagreeable anticipation of a bump at the end of the journey. And when she got to the top how wonderfully different it looked from anything she could have expected! The doors stood open, and Griselda found them quite big enough, or herself quite small enough—which it was she couldn't tell, and as it was all a matter of fancy she decided not to trouble to inquire—to pass through quite comfortably.

And inside there was the most charming little snuggery imaginable. It was something like a saloon railway carriage—it seemed to be all lined and carpeted and everything, with rich mossy red velvet; there was a little round table in the middle and two arm-chairs, on one of which sat the cuckoo—"quite like other people," thought Griselda to herself—while the other, as he pointed out to Griselda by a little nod, was evidently intended for her.

"Thank you," said she, sitting down on the chair as she spoke.

"Are you comfortable?" inquired the cuckoo.

"Quite," replied Griselda, looking about her with great satisfaction. "Are all cuckoo clocks like this when you get up inside them?" she inquired. "I can't think how there's room for this dear little place between the clock and the wall. Is it a hole cut out of the wall on purpose, cuckoo?"

"are you comfortable?" inquired the cuckoo

"Hush!" said the cuckoo, "we've got other things to talk about. First, shall I lend you one of my mantles? You may feel cold."

"I don't just now," replied Griselda; "but perhaps I might."

She looked at her little bare feet as she spoke, and wondered why they weren't cold, for it was very chilblainy weather.

The cuckoo stood up, and with one of his claws reached from a corner where it was hanging a cloak which Griselda had not before noticed. For it was hanging wrong side out, and the lining was red velvet, very like what the sides of the little room were covered with, so it was no wonder she had not noticed it.

Had it been hanging the right side out she must have done so; this side was so very wonderful!

It was all feathers—feathers of every shade and colour, but beautifully worked in, somehow, so as to lie quite smoothly and evenly, one colour melting away into another like those in a prism, so that you could hardly tell where one began and another ended.

"What a lovely cloak!" said Griselda, wrapping it round her and feeling even more comfortable than before, as she watched the rays of the little lamp in the roof—I think I was forgetting to tell you that the cuckoo's boudoir was lighted by a dear little lamp set into the red velvet roof like a pearl in a ring—playing softly on the brilliant colours of the feather mantle.

"It's better than lovely," said the cuckoo, "as you shall see. Now, Griselda," he continued, in the tone of one coming to business—"now, Griselda, let us talk."

"We have been talking," said Griselda, "ever so long. I am very comfortable. When you say 'let us talk' like that, it makes me forget all I wanted to say. Just let me sit still and say whatever comes into my head."

"That won't do," said the cuckoo; "we must have a plan of action."

"A what?" said Griselda.

"You see you have a great deal to learn," said the cuckoo triumphantly. "You don't understand what I say."

"But I didn't come up here to learn," said Griselda; "I can do that down there;" and she nodded her head in the direction of the ante-room table. "I want to play."

"Just so," said the cuckoo; "that's what I want to talk about. What do you call 'play'—blindman's-buff and that sort of thing?"

"No," said Griselda, considering. "I'm getting rather too big for that kind of play. Besides, cuckoo, you and I alone couldn't have much fun at blindman's-buff; there'd be only me to catch you or you to catch me."

"Oh, we could easily get more," said the cuckoo. "The mandarins would be pleased to join."

"The mandarins!" repeated Griselda. "Why, cuckoo, they're not alive! How could they play?"

The cuckoo looked at her gravely for a minute, then shook his head.

"You have a great deal to learn," he said solemnly. "Don't you know that everything's alive?"

"No," said Griselda, "I don't; and I don't know what you mean, and I don't think I want to know what you mean. I want to talk about playing."

"Well," said the cuckoo, "talk."

"What I call playing," pursued Griselda, "is—I have thought about it now, you see—is being amused. If you will amuse me, cuckoo, I will count that you are playing with me."

"How shall I amuse you?" inquired he.

"Oh, that's for you to find out!" exclaimed Griselda. "You might tell me fairy stories, you know: if you're a fairy you should know lots; or—oh yes, of course that would be far nicer—if you are a fairy you might take me with you to fairyland."

Again the cuckoo shook his head.

"That," said he, "I cannot do."

"Why not?" said Griselda. "Lots of children have been there."

"I doubt it," said the cuckoo. "Some may have been, but not lots. And some may have thought they had been there who hadn't really been there at all. And as to those who have been there, you may be sure of one thing—they were not taken, they found their own way. No one ever was taken to fairyland—to the real fairyland. They may have been taken to the neighbouring countries, but not to fairyland itself."

"And how is one ever to find one's own way there?" asked Griselda.

"That I cannot tell you either," replied the cuckoo. "There are many roads there; you may find yours some day. And if ever you do find it, be sure you keep what you see of it well swept and clean, and then you may see further after a while. Ah, yes, there are many roads and many doors into fairyland!"

"Doors!" cried Griselda. "Are there any doors into fairyland in this house?"

"Several," said the cuckoo; "but don't waste your time looking for them at present. It would be no use."

"Then how will you amuse me?" inquired Griselda, in a rather disappointed tone.

"Don't you care to go anywhere except to fairyland?" said the cuckoo.

"Oh yes, there are lots of places I wouldn't mind seeing. Not geography sort of places—it would be just like lessons to go to India and Africa and all those places—but queer places, like the mines where the goblins make diamonds and precious stones, and the caves down under the sea where the mermaids live. And—oh, I've just thought—now I'm so nice and little, I would like to go all over the mandarins' palace in the great saloon."

"That can be easily managed," said the cuckoo; "but—excuse me for an instant," he exclaimed suddenly. He gave a spring forward and disappeared. Then Griselda heard his voice outside the doors, "Cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo." It was three o'clock.

The doors opened again to let him through, and he re-settled himself on his chair. "As I was saying," he went on, "nothing could be easier. But that palace, as you call it, has an entrance on the other side, as well as the one you know."

"Another door, do you mean?" said Griselda. "How funny! Does it go through the wall? And where does it lead to?"

"It leads," replied the cuckoo, "it leads to the country of the Nodding Mandarins."

"What fun!" exclaimed Griselda, clapping her hands. "Cuckoo, do let us go there. How can we get down? You can fly, but must I slide down the chain again?"

"Oh dear, no," said the cuckoo, "by no means. You have only to stretch out your feather mantle, flap it as if it was wings— so"—he flapped his own wings encouragingly—"wish, and there you'll be."

"Where?" said Griselda bewilderedly.

"Wherever you wish to be, of course," said the cuckoo. "Are you ready? Here goes."

"Wait—wait a moment," cried Griselda. "Where am I to wish to be?"

"Bless the child!" exclaimed the cuckoo. "Where do you wish to be? You said you wanted to visit the country of the Nodding Mandarins."

"Yes; but am I to wish first to be in the palace in the great saloon?"

"Certainly," replied the cuckoo. "That is the entrance to Mandarin Land, and you said you would like to see through it. So—you're surely ready now?"

"A thought has just struck me," said Griselda. "How will you know what o'clock it is, so as to come back in time to tell the next hour? My aunts will get into such a fright if you go wrong again! Are you sure we shall have time to go to the mandarins' country to-night?"

"Time!" repeated the cuckoo; "what is time? Ah, Griselda, you have a very great deal to learn! What do you mean by time?"

"I don't know," replied Griselda, feeling rather snubbed. "Being slow or quick—I suppose that's what I mean."

"And what is slow, and what is quick?" said the cuckoo. "All a matter of fancy! If everything that's been done since the world was made till now, was done over again in five minutes, you'd never know the difference."

"Oh, cuckoo, I wish you wouldn't!" cried poor Griselda; "you're worse than sums, you do so puzzle me. It's

Comments (0)