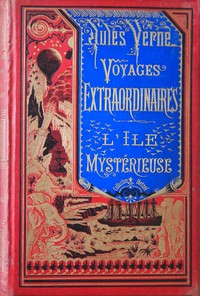

The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗». Author Jules Verne

The colonists soon reached that part of the stern where the poop formerly stood. It was here Ayrton told them they must search for the powder magazine. Smith, believing that this had not exploded, thought they might save some barrels, and that the powder, which is usually in metal cases, had not been damaged by the water. In fact, this was just what had happened. They found, among a quantity of projectiles, at least twenty barrels, which were lined with copper, and which they pulled out with great care. Pencroff was now convinced by his own eyes that the destruction of the Speedy could not have been caused by an explosion. The part of the hull in which the powder magazine was situated was precisely the part which had suffered the least.

“It may be so,” replied the obstinate sailor, “but as to a rock, there is not one in the channel.” Then he added:—”I know nothing about it, even Mr. Smith does not know. No one knows, or ever will.”

Several hours passed in these researches, and the tide was beginning to rise. They had to stop their work of salvage, but there was no fear that the wreck would be washed out to sea, for it was as solidly imbedded as if it had been anchored to the bottom. They could wait with impunity for the turn of the tide to commence operations. As to the ship itself, it was of no use; but they must hasten to save the debris of the hull, which would not take long to disappear in the shifting sands of the channel.

It was 5 o’clock in the afternoon. The day had been a hard one, and they sat down to their dinner with great appetite; but afterwards, notwithstanding their fatigue, they could not resist the desire of examining some of the chests. Most of them contained ready-made clothes, which, as may be imagined, were very welcome. There was enough to clothe a whole colony, linen of every description, boots of all sizes.

“Now we are too rich,” cried Pencroff. “What shall we do with all these things?”

Every moment the sailor uttered exclamations of joy, as he came upon barrels of molasses and rum, hogsheads of tobacco, muskets and side-arms, bales of cotton, agricultural implements, carpenters’ and smiths’ tools, and packages of seeds of every kind, uninjured by their short sojourn in the water. Two years before, how these things would have come in season! But even now that the industrious colonists were so well supplied, these riches would be put to use.

There was plenty of storage room in Granite House, but time failed them now to put everything in safety. They must not forget that six survivors of the Speedy’s crew were now on the island, scoundrels of the deepest dye, against whom they must be on their guard.

Although the bridge over the Mercy and the culverts had been raised, the convicts would make little account of a river or a brook; and, urged by despair, these rascals would be formidable. Later, the colonists could decide what course to take with regard to them; in the meantime, the chests and packages piled up near the Chimneys must be watched over, and to this they devoted themselves during the night.

The night passed, however, without any attack from the convicts. Master Jup and Top, of the Granite House guard, would have been quick to give notice.

The three days which followed, the 19th, 20th, and 21st of October, were employed in carrying on shore everything of value either in the cargo or in the rigging. At low tide they cleaned out the hold, and at high tide, stowed away their prizes. A great part of the copper sheathing could be wrenched from the hull, which every day sank deeper; but before the sands had swallowed up the heavy articles which had sunk to the bottom, Ayrton and Pencroff dived and brought up the chains and anchors of the brig, the iron ballast, and as many as four cannon, which could be eased along upon empty barrels and brought to land; so that the arsenal of the colony gained as much from the wreck as the kitchens and store-rooms. Pencroff, always enthusiastic in his projects, talked already about constructing a battery which should command the channel and the mouth of the river. With four cannon, he would guarantee to prevent any fleet, however powerful, from coming within gunshot of the island.

Meanwhile, after nothing of the brig had been left but a useless shell, the bad weather came to finish its destruction. Smith had intended to blow it up, so as to collect the debris on shore, but a strong northeast wind and a high sea saved his powder for him. On the night of the 23d, the hull was thoroughly broken up, and part of the wreck stranded on the beach. As to the ship’s papers, it is needless to say, although they carefully rummaged the closet in the poop, Smith found no trace of them. The pirates had evidently destroyed all that concerned either the captain or the owner of the Speedy, and as the name of its port was not painted on the stern, there was nothing to betray its nationality. However, from the shape of the bow, Ayrton and Pencroff believed the brig to be of English construction.

A week after the ship went down, not a trace of her was to be seen even at low tide. The wreck had gone to pieces, and Granite House had been enriched with almost all its contents. But the mystery of its strange destruction would never have been cleared up, if Neb, rambling along the beach, had not come upon a piece of a thick iron cylinder, which bore traces of an explosion. It was twisted and torn at the edge, as if it had been submitted to the action of an explosive substance. Neb took it to his master, who was busy with his companions in the workshop at the Chimneys. Smith examined it carefully, and then turned to Pencroff.

“Do you still maintain, my friend,” said he, “that the Speedy did not perish by a collision?”

“Yes, Mr. Smith,” replied the sailor, “you know as well as I that there are no rocks in the channel.”

“But suppose it struck against this piece of iron?” said the engineer, showing the broken cylinder.

“What, that pipe stem!” said Pencroff, incredulously.

“Do you remember, my friends,” continued Smith, “that before foundering the brig was lifted up by a sort of waterspout?”

“Yes, Mr. Smith,” said Herbert.

“Well, this was the cause of the waterspout,” said Smith, holding up the broken tube.

“That?” answered Pencroff.

“Yes; this cylinder is all that is left of a torpedo!”

“A torpedo!” cried they all.

“And who put a torpedo there?” asked Pencroff, unwilling to give up.

“That I cannot tell you,” said Smith, “but there it was, and you witnessed its tremendous effects!”

CHAPTER XLVIITHE ENGINEER’S THEORY—PENCROFF’S MAGNIFICENT SUPPOSITIONS—A BATTERY IN THE AIR—FOUR PROJECTILES—THE SURVIVING CONVICTS—AYRTON HESITATES—SMITH’S GENEROSITY AND PENCROFF’S DISSATISFACTION.

Thus, then, everything was explained by the submarine action of this torpedo. Smith had had some experience during the civil war of these terrible engines of destruction, and was not likely to be mistaken. This cylinder, charged with nitro-glycerine, had been the cause of the column of water rising in the air, of the sinking of the brig, and of the shattered condition of her hull. Everything was accounted for, except the presence of this torpedo in the waters of the channel!

“My friends,” resumed Smith, “we can no longer doubt the existence of some mysterious being, perhaps a castaway like ourselves, inhabiting our island. I say this that Ayrton may be informed of all the strange events which have happened for two years. Who our unknown benefactor may be, I cannot say, nor why he should hide himself after rendering us so many services; but his services are not the less real, and such as only a man could render who wielded some prodigious power. Ayrton is his debtor as well; as he saved me from drowning after the fall of the balloon, so he wrote the document, set the bottle afloat in the channel, and gave us information of our comrade’s condition. He stranded on Jetsam Point that chest, full of all that we needed; he lighted that fire on the heights of the island which showed you where to land; he fired that ball which we found in the body of the peccary; he immersed in the channel that torpedo which destroyed the brig; in short, he has done all those inexplicable things of which we could find no explanation. Whatever he is, then, whether a castaway or an exile, we should be ungrateful not to feel how much we owe him. Some day, I hope, we shall discharge our debt.”

“We may add,” replied Spilett, “that this unknown friend has a way of doing things which seems supernatural. If he did all these wonderful things, he possesses a power which makes him master of the elements.”

“Yes,” said Smith, “there is a mystery here, but if we discover the man we shall discover the mystery also. The question is this:—Shall we respect the incognito of this generous being, or should we try to find him? What do you think?”

“Master,” said Neb, “I have an idea that we may hunt for him as long as we please, but that we shall only find him when he chooses to make himself known.”

“There’s something in that, Neb,” said Pencroff.

“I agree with you, Neb,” said Spilett; “but that is no reason for not making the attempt. Whether we find this mysterious being or not, we shall have fulfilled our duty towards him.”

“And what is your opinion, my boy?” said the engineer, turning to Herbert.

“Ah,” cried Herbert, his eye brightening; “I want to thank him, the man who saved you first and now has saved us all.”

“It wouldn’t be unpleasant for any of us, my boy,” returned Pencroff. “I am not curious, but I would give one of my eyes to see him face to face.”

“And you, Ayrton?” asked the engineer.

“Mr. Smith,” replied Ayrton, “I can give no advice. Whatever you do will be right, and whenever you want my help in your search, I am ready.”

“Thanks, Ayrton,” said Smith, “but I want a more direct answer. You are our comrade, who has offered his life more than once to save ours, and we will take no important step without consulting you.”

“I think, Mr. Smith,” replied Ayrton, “that we ought to do everything to discover our unknown benefactor. He may be sick or suffering. I owe him a debt of gratitude which I can never forget, for he brought you to save me. I will never forget him!”

“It is settled,” said Smith. “We will begin our search as soon as possible. We will leave no part of the island unexplored. We will pry into its most secret recesses, and may our unknown friend pardon our zeal!”

For several days the colonists were actively at work haymaking and harvesting. Before starting upon their exploring tour, they wanted to finish all their important labors. Now, too, was the time for gathering the vegetable products of Tabor Island. Everything had to be stored; and, happily, there was plenty of room in Granite House for all the riches of the island. There all was ranged in order, safe from man or beast. No dampness was to be feared in the midst of this solid mass of granite. Many of the natural excavations in the upper corridor were enlarged by the pick, or blown out by mining, and Granite House thus became a receptacle for all the goods of the colony.

The brig’s guns were pretty pieces of cast-steel, which, at Pencroff’s instance, were hoisted, by means of tackle and cranes, to the very entrance of Granite House; embrasures were constructed between the windows, and soon they could be seen stretching their shining nozzles through the granite wall. From this height these fire-breathing gentry had the range of all Union Bay. It was a little Gibraltar, to whose fire every ship off the islet would inevitably be exposed.

“Mr. Smith,” said Pencroff one day—it was the 8th of November—“now that we have mounted our guns, we ought to try their range.”

“For what purpose?”

“Well, we ought to know how far we can send a ball.”

“Try, then, Pencroff,” answered the engineer; “but don’t use our powder, whose stock I do not want to diminish; use pyroxyline, whose supply will never fail.”

“Can these cannon support the explosive force of pyroxyline?” asked the reporter, who was as eager as Pencroff to try their new artillery.

“I think so. Besides,” added the engineer, “we will be careful.”

Smith had good reason to think that these

Comments (0)