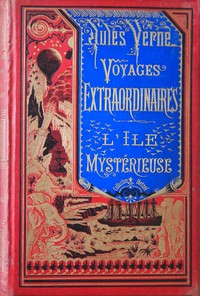

The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island, Jules Verne [classic novels .txt] 📗». Author Jules Verne

“Now,” said Smith, “the initial velocity being a question of the amount of powder in the charge, everything depends upon the resisting power of the metal; and steel is undeniably the best metal in this respect; so that I have great hope of our battery.”

The four cannon were in perfect condition. Ever since they had been taken out of the water, Pencroff had made it his business to give them a polish. How many hours had been spent in rubbing them, oiling them, and cleaning the separate parts! By this time they shone as if they had been on board of a United States frigate.

That very day, in the presence of all the colony, including Jup and Top, the new guns were successively tried. They were charged with pyroxyline, which, as we have said, has an explosive force fourfold that of gunpowder; the projectile was cylindro-conical in shape. Pencroff, holding the fuse, stood ready to touch them off.

Upon a word from Smith, the shot was fired. The ball, directed seaward, passed over the islet and was lost in the offing, at a distance which could not be computed.

The second cannon was trained upon the rocks terminating Jetsam Point, and the projectile, striking a sharp boulder nearly three miles from Granite House, made it fly into shivers. Herbert had aimed and fired the shot, and was quite proud of his success. But Pencroff was prouder of it even than he. Such a feather in his boy’s cap!

The third projectile, aimed at the downs which formed the upper coast of Union Bay, struck the sand about four miles away, then ricocheted into the water. The fourth piece was charged heavily to test its extreme range, and every one got out of the way for fear it would burst; then the fuse was touched off by means of a long string. There was a deafening report, but the gun stood the charge, and the colonists, rushing to the windows, could see the projectile graze the rocks of Mandible Cape, nearly five miles from Granite House, and disappear in Shark Gulf.

“Well, Mr. Smith,” said Pencroff, who had cheered at every shot, “what do you say to our battery? I should like to see a pirate land now!”

“Better have them stay away, Pencroff,” answered the engineer.

“Speaking of that,” said the sailor, “what are we going to do with the six rascals who are prowling about the island? Shall we let them roam about unmolested? They are wild beasts, and I think we should treat them as such. What do you think about it, Ayrton?” added Pencroff, turning towards his companion.

Ayrton hesitated for a moment, while Smith regretted the abrupt question, and was sincerely touched when Ayrton answered humbly:—

“I was one of these wild beasts once, Mr. Pencroff, and I am not worthy to give counsel.”

And, with bent head, he walked slowly away. Pencroff understood him.

“Stupid ass that I am!” cried he. “Poor Ayrton! and yet he has as good a right to speak as any of us. I would rather have bitten off my tongue than have given him pain! But, to go back to the subject, I think these wretches have no claim to mercy, and that we should rid the island of them.”

“And before we hunt them down, Pencroff, shall we not wait for some fresh act of hostility?”

“Haven’t they done enough already?” said the sailor, who could not understand these refinements.

“They may repent,” said Smith.

“They repent!” cried the sailor, shrugging his shoulders.

“Think of Ayrton, Pencroff!” said Herbert, taking his hand. “He has become an honest man.”

Pencroff looked at his companions In stupefaction. He could not admit the possibility of making terms with the accomplices of Harvey, the murderers of the Speedy’s crew.

“Be it so!” he said. “You want to be magnanimous to these rascals. May we never repent of it!”

“What danger do we run if we are on our guard?” said Herbert.

“H’m!” said the reporter, doubtfully. “There are six of them, well armed. If each of them sighted one of us from behind a tree—”

“Why haven’t they tried it already?” said Herbert. “Evidently it was not their cue.”

“Very well, then,” said the sailor, who was stubborn in his opinion, “we will let these worthy fellows attend to their innocent occupations without troubling our heads about them.”

“Pencroff,” said the engineer, “you have often shown respect for my opinions. Will you trust me once again?”

“I will do whatever you say, Mr. Smith,” said the sailor, nowise convinced.

“Well, let us wait, and not be the first to attack.”

This was the final decision, with Pencroff in the minority. They would give the pirates a chance, which their own interest might induce them to seize upon, to come to terms. So much, humanity required of them. But they would have to be constantly on their guard, and the situation was a very serious one. They had silenced Pencroff, but, perhaps, after all, his advice would prove sound.

CHAPTER XLVIII.THE PROJECTED EXPEDITION—AYRTON AT THE CORRAL—VISIT TO PORT BALLOON—PENCROFF’S REMARKS—DESPATCH SENT TO THE CORRAL—NO ANSWER FROM AYRTON—SETTING OUT NEXT DAY—WHY THE WIRE DID NOT ACT—A DETONATION.

Meanwhile the thing uppermost in the colonists’ thought was to achieve the complete exploration of the island which had been decided upon, an exploration which now would have two objects: —First, to discover the mysterious being whose existence was no longer a matter of doubt; and, at the same time to find out what had become of the pirates, what hiding place they had chosen, what sort of life they were leading, and what was to be feared from them.

Smith would have set off at once, but as the expedition would take several days, it seemed better to load the wagon with all the necessaries for camping out. Now at this time one of the onagers, wounded in the leg, could not bear harness; it must have several days’ rest, and they thought it would make little difference if they delayed the departure a week, that is, till November 20. November in this latitude corresponds to the May of the Northern Hemisphere, and the weather was fine. They were now at the longest days in the year, so that everything was favorable to the projected expedition, which, if it did not attain its principal object, might be fruitful in discoveries, especially of the products of the soil; for Smith intended to explore those thick forests of the Far West, which stretched to the end of Serpentine Peninsula.

During the nine days which would precede their setting out, it was agreed that they should finish work on Prospect Plateau. But Ayrton had to go back to the corral to take care of their domesticated animals. It was settled that he should stay there two days, and leave the beasts with plenty of fodder. Just as he was setting out, Smith asked him if he would like to have one of them with him, as the island was no longer secure. Ayrton replied that it would be useless, as he could do everything by himself, and that there was no danger to fear. If anything happened at or near the corral, he would instantly acquaint the colonists of it by a telegram sent to Granite House.

So Ayrton drove off in the twilight, about 9 o’clock, behind one onager, and two hours afterwards the electric wire gave notice that he had found everything in order at the corral.

During these two days Smith was busy at a project which would finally secure Granite House from a surprise. The point was to hide completely the upper orifice of the former weir, which had been already blocked up with stones, and half hidden under grass and plants, at the southern angle of Lake Grant. Nothing could be easier, since by raising the level of the lake two or three feet, the hole would be entirely under water.

Now to raise the level, they had only to make a dam across the two trenches by which Glycerine Creek and Waterfall Creek were fed. The colonists were incited to the task, and the two dams, which were only seven or eight feet long, by three feet high, were rapidly erected of closely cemented stones. When the work had been done, no one could have suspected the existence of the subterranean conduit. The little stream which served to feed the reservoir at Granite House, and to work the elevator, had been suffered to flow in its channel, so that water might never be wanting. The elevator once raised, they might defy attack.

This work had been quickly finished, and Pencroff, Spilett, and Herbert found time for an expedition to Port Balloon. The sailor was anxious to know whether the little inlet up which the Good Luck was moored had been visited by the convicts.

“These gentry got to land on the southern shore,” he observed, “and if they followed the line of the coast they may have discovered the little harbor, in which case I wouldn’t give half a dollar for our Good Luck.”

So off the three went in the afternoon of November 10. They were well armed, and as Pencroff slipped two bullets into each barrel of his gun, he had a look which presaged no good to whoever came too near, “beast or man,” as he said. Neb went with them to the elbow of the Mercy, and lifted the bridge after them. It was agreed that they should give notice of their return by firing a shot, when Neb would come back to put down the bridge.

The little band walked straight for the south coast. The distance was only three miles and a half, but they took two hours to walk it. They searched on both sides of the way, both the forest and Tadorn’s Fens; but they found no trace of the fugitives. Arriving at Port Balloon, they saw with great satisfaction that the Good Luck was quietly moored in the narrow inlet, which was so well hidden by the rocks that it could be seen neither from sea nor shore, but only from directly above or below.

“After all,” said Pencroff, “the rascals haven’t been here. The vipers like tall grass better, and we shall find them in the Far-West.”

“And it’s a fortunate thing,” added Herbert, “for if they had found the Good Luck, they would have made use of her in getting away, and we could never have gone back to Tabor Island.”

“Yes,” replied the reporter, “it will be important to put a paper there stating the situation of Lincoln Island, Ayrton’s new residence, in case the Scotch yacht should come after him.”

“Well, here is our Good Luck, Mr. Spilett,” said the sailor, “ready to start with her crew at the first signal!”

Talking thus, they got on board and walked about the deck. On a sudden the sailor, after examining the bit around which the cable of the anchor was wound, cried,

“Hallo! this is a bad business!”

“What’s the matter, Pencroff?” asked the reporter.

“The matter is that that knot was never tied by me——”

And Pencroff pointed to a rope which made the cable fast to the bit, so as to prevent its tripping.

“How, never tied by you?” asked Spilett.

“No, I can swear to it. I never tie a knot like that.”

“You are mistaken, Pencroff.”

“No, I’m not mistaken,” insisted the sailor. “That knot of mine is second nature with me.”

“Then have the convicts been on board?” asked Herbert.

“I don’t know,” said Pencroff, “but somebody has certainly raised and dropped this anchor!”

The sailor was so positive that neither Spilett nor Herbert could contest his assertion. It was evident that the beat had shifted place more or less since Pencroff had brought it back to Balloon Harbor. As for the sailor, he had no doubt that the anchor had been pulled up and cast again. Now, why had these manœuvres taken place unless the boat had been used on some expedition?

“Then why did we not see the Good Luck pass the offing?” said the reporter, who wanted to raise every possible objection.

“But, Mr. Spilett,” answered the sailor, “they could have set out in the night with a good wind, and in two hours have been out of sight of the island.”

“Agreed,” said Spilett, but I still ask with what object the convicts used the Good Luck, and why, after using her, they brought her back to port?”

“Well, Mr. Spilett,” said the sailor, “we will have to include that among our mysterious incidents, and think no more of it. One thing is certain, the Good Luck was there, and is here! If the convicts take it a second time, it may never find its way back

Comments (0)