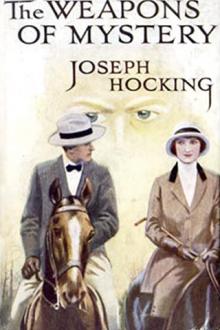

The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗

- Author: Joseph Hocking

- Performer: -

Book online «The Weapons of Mystery, Joseph Hocking [the beach read .txt] 📗». Author Joseph Hocking

I did not change carriages as I intended. Miss Staggles got tired after awhile, and so there was relief in that quarter, while my seat was most comfortable, and I did not want to be disturbed. Hour after hour passed by, until night came on; then the wind blew colder, and I began to wonder how soon the journey would end, when the collector came to take all the tickets from the Leeds passengers. Shortly after we arrived at the Midland station, for which I was truly thankful. I did not wait there long; a train stood at another platform, which stopped at a station some two miles from Tom Temple's home. By this time there was every evidence of the holiday season. The train was crowded, and I was glad to get in at all, unmindful of comfort.

What had become of my two travelling companions I was not aware, but concluded that they would be staying at Leeds, as they had given up their tickets at the collecting station. I cannot but admit, however, that I was somewhat anxious as to the destination of Gertrude Forrest, for certainly she had made an impression upon me I was not likely to forget. Still I gave up the idea of ever seeing her again, and tried to think of the visit I was about to pay.

Arrived at the station, I saw Tom Temple, who gave me a hearty welcome, after which he said, "Justin, my boy, do you want to be introduced to some ladies at present?"

"A thousand times no," I replied. "Let's wait till we get to Temple

Hall."

"Then, in that case, you will have to go home in a cab. I retained one for you, knowing your dislike to the fair sex; for, of course, they will have to go in the carriage, and I must go with them. Stay, though. I'll go and speak to them, and get them all safe in the carriage, and then, as there will be barely room for me, I'll come back and ride home with you."

He rushed away as he spoke, and in a few minutes came back again. "I am sorry those ladies had to be made rather uncomfortable, but guests have been arriving all the day, and thus things are a bit upset. There are five people in yon carriage; three came from the north, and two from the south. The northern train has been in nearly half-an-hour, so the three had to wait for the two. Well, I think I've made them comfortable, so I don't mind so much."

"You're a capital host, Tom," I said.

"Am I, Justin? Well, I hope I am to you, for I have been really longing for you to come, and I want you to have a jolly time."

"I'm sure I shall," I replied.

"Well, I hope so; only you don't care for ladies' society, and I'm afraid I shall have to be away from you a good bit."

"Naturally you will, old fellow. You see, you are master of the hall, and will have to look after the comfort of all the guests."

"Oh, as to that, mother will do all that's necessary; but I—that is—" and Tom stopped.

"Any particular guest, Tom?" I asked.

"Yes, there is, Justin. I don't mind telling you, but I'm in love, and I want to settle the matter this Christmas. She's an angel of a girl, and I'm in hopes that—Well, I don't believe she hates me."

"Good, Tom. And her name?"

"Her name," said Tom slowly, "is Edith Gray."

I gave a sigh of relief. I could not help it—why I could not tell; and yet I trembled lest he should mention another name.

We reached Temple Hall in due time, where I was kindly welcomed by Mrs. Temple and her two daughters. The former was just the kind of lady I had pictured her, while the daughters gave promise of following in the footsteps of their kind-hearted mother.

Tom took me to my room, and then, looking at his watch, said, "Make haste, old fellow. Dinner has been postponed on account of you late arrivals, but it will be ready in half-an-hour."

I was not long over my toilet, and soon after hearing the first dinner bell I wended my way to the drawing-room, wondering who and what kind of people I should meet, but was not prepared for the surprises that awaited me.

CHAPTER II CHRISTMAS EVEJust before I reached the drawing-room door, Mrs. Temple came up and took me by the arm.

"We are all going to be very unceremonious, Mr. Blake," she said, "and I shall expect my son's friend to make himself perfectly at home."

I thanked her heartily, for I began to feel a little strange.

We entered the drawing-room together, where I found a number of people had gathered. They were mostly young, although I saw one or two ancient-looking dames, who, I supposed, had come to take care of their daughters.

"I am going to introduce you to everybody," continued the old lady, "for this is to be a family gathering, and we must all know each other. I know I may not be acting according to the present usages of society, but that does not trouble me a little bit."

Accordingly, with the utmost good taste, she introduced me to a number of the people who had been invited.

I need make no special mention of most of them. Some of the young ladies simpered, others were frank, some were fairly good looking, while others were otherwise, and that is about all that could be said. None had sufficient individuality to make a distinct impression upon me. The young men were about on a par with the young ladies. Some lisped and were affected, some were natural and manly; and I began to think that, as far as the people were concerned, the Christmas gathering would be a somewhat tame affair.

This thought had scarcely entered my mind when two men entered the room, who were certainly not of the ordinary type, and will need a few words of description; for both were destined, as my story will show, to have considerable influence over my life.

I will try to describe the more striking of the two first.

He was a young man. Not more than thirty-five. He was fairly tall, well built, and had evidently enjoyed the education and advantages of a man of wealth. His hair was black as the raven's wings, and was brushed in a heavy mass horizontally across his forehead. His eyes were of a colour that did not accord with his black hair and swarthy complexion. They were of an extremely light grey, and were tinted with a kind of green. They were placed very close together, and, the bridge of the nose being narrow, they appeared sometimes as if only one eye looked upon you. The mouth was well cut, the lips rather thin, which often parted, revealing a set of pearly white teeth. There was something positively fascinating about the mouth, and yet it betrayed malignity—cruelty. He was perfectly self-possessed, stood straight, and had a soldier-like bearing. I instinctively felt that this was a man of power, one who would endeavour to make his will law. His movements were perfectly graceful, and from the flutter among the young ladies when he entered, I judged he had already spent some little time with them, and made no slight impression.

His companion was much smaller, and even darker than he was. His every feature indicated that he was not an Englishman. With small wiry limbs, black, restless, furtive eyes, rusty black hair, and a somewhat unhealthy colour in his face, he formed a great contrast to the man I have just tried to describe. I did not like him. He seemed to carry a hundred secrets around with him, and each one a deadly weapon he would some day use against any who might offend him. He, too, gave you the idea of power, but it was the power of a subordinate.

Instinctively I felt that I should have more to do with these men than with the rest of the company present.

Although I have used a page of good paper in describing them, I was only a very few seconds in seeing and realizing what I have written.

Both walked up to us, and both smiled on Mrs. Temple, whereupon she introduced them. The first had a peculiar name; at least, so it seemed to me.

"Mr. Herod Voltaire—Mr. Justin Blake," she said; and instantly we were looking into each other's eyes, I feeling a strange kind of shiver pass through me.

The name of the smaller man was simply that of an Egyptian, "Aba Wady

Kaffar." The guests called him Mr. Kaffar, and thus made it as much

English as possible.

Scarcely had the formalities of introduction been gone through between the Egyptian and myself, when my eyes were drawn to the door, which was again opening. Do what I would I could not repress a start, for, to my surprise, I saw my travelling companions enter with Miss Temple—Gertrude Forrest looking more charming and more beautiful than ever, and beside her Miss Staggles, tall, gaunt, and more forbidding than when in the railway carriage.

It is no use denying the fact, for my secret must sooner or later drop out. My heart began to throb wildly, while my brain seemed on fire. I began to picture myself in conversation with her, and becoming acquainted with her, when I accidentally looked at Herod Voltaire. His eyes were fixed on Miss Forrest, as if held by a magnet, and I fancied I saw a faint colour tinge his cheek.

What I am now going to write may appear foolish and unreal, especially when you remember that I was thirty years of age, but the moment I saw his ardent, admiring gaze, I felt madly jealous.

The second dinner bell rang, and so, mechanically offering my arm to a lady who had, I thought, been neglected on account of her plain looks, I followed the guests to the dining-room.

Nothing happened there worth recording. We had an old-fashioned English dinner, and that is about all I can remember, except that the table looked exceedingly nice. I don't think there was much talking; evidently the guests were as yet strangers to each other, and were only gradually wearing away the restraint that naturally existed. I could not see Miss Gertrude Forrest, for she was sitting on my side of the table, but I could see the peculiar eyes of Herod Voltaire constantly looking at some one nearly opposite him, while he scarcely touched the various dishes that were placed on the table.

Presently dinner came to an end. The ladies retired to the drawing-room, while the gentlemen prepared to sit over their wine. Being an abstainer, I asked leave to retire with the ladies. I did this for two reasons besides my principles of abstinence. First, I thought the custom a foolish one, as well as being harmful; and, second, I hoped by entering the drawing-room early, I might have a chance to speak to Miss Forrest.

I did not leave alone. Two young Englishmen also declared themselves to be abstainers, and wanted to go with me, while Herod Voltaire likewise asked leave to abide by the rules he had ever followed in the countries in which he had lived.

Of course there was some laughing demur among those who enjoyed their after-dinner wine, but we followed the bent of our inclination, and found our way to the drawing-room.

Evidently the ladies were not sorry to see us, for a look of pleasure and surprise greeted us, and soon the conversation became general. Presently, however, our attention was by degrees drawn to that part of the room where Herod Voltaire sat, and I heard him speaking fluently and smoothly on some subject he was discussing with a young lady.

"Yes, Miss Emery," he said, "I think European education is poor, is one-sided. Take, for example, the ordinary English education, and what does it amount to? Arithmetic, and sometimes a little mathematics, reading, writing, French, sometimes German, and of course music and dancing. Nearly all are educated in one groove, until there is in the English mind an amount of sameness that becomes monotonous."

"You are speaking of the education of ladies, Mr. Voltaire?" said Miss

Emery.

"Yes, more particularly, although there is but little more variation among the men. Take your University degrees—your Cambridge

Comments (0)