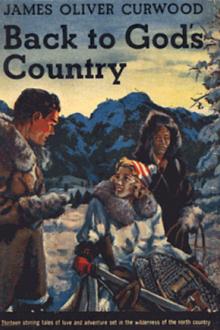

Back to God's Country and Other Stories, James Oliver Curwood [hot novels to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: James Oliver Curwood

- Performer: -

Book online «Back to God's Country and Other Stories, James Oliver Curwood [hot novels to read .TXT] 📗». Author James Oliver Curwood

He was staggering when he rose. The blood ran in streams from his mouth and nose. His beard dripped with it. His yellow teeth were caved in.

This time he did not leap upon the platform—he clambered back to it, and the hooded stranger gave him a lift which a few minutes before Dupont would have resented as an insult.

“Ah, it has come,” said the stranger to Delesse.

“He is the best close-in fighter in all—”

He did not finish.

“I could kill you now—kill you with a single blow,” said Reese Beaudin in a moment when the giant stood swaying. “But there is a greater punishment in store for you, and so I shall let you live!”

And now Reese Beaudin was facing that part of the crowd where the woman he loved was standing. He was breathing deeply. But he was not winded. His eyes were black as night, his hair wind-blown. He looked straight over the heads between him and she whom Dupont had stolen from him.

Reese Beaudin raised his arms, and where there had been a murmur of voices there was now silence.

For the first time the stranger threw back his hood. He was unbuttoning his heavy coat.

And Joe Delesse, looking up, saw that Reese Beaudin was making a mighty effort to quiet a strange excitement within his breast. And then there was a rending of cloth and of buttons and of pins as in one swift movement he tore the shirt from his own breast—exposing to the eyes of Lac Bain blood-red in the glow of the winter sun, the crimson badge of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police!

And above the gasp that swept the multitude, above the strange cry of the woman, his voice rose:

“I am Reese Beaudin, the Yellow-back. I am Reese Beaudin, who ran away. I am Reese Beaudin,—Sergeant in His Majesty’s Royal Northwest Mounted Police, and in the name of the law I arrest Jacques Dupont for the murder of Francois Bedore, who was killed on his trap-line five years ago! Fitzgerald—”

The hooded stranger leaped upon the platform. His heavy coat fell off. Tall and grim he stood in the scarlet jacket of the Police. Steel clinked in his hands. And Jacques Dupont, terror in his heart, was trying to see as he groped to his knees. The steel snapped over his wrists.

And then he heard a voice close over him. It was the voice of Reese Beaudin.

“And this is your final punishment, Jacques Dupont—to be hanged by the neck until you are dead. For Bedore was not dead when Elise’s father left him after their fight on the trap-line. It was you who saw the fight, and finished the killing, and laid the crime on Elise’s father. Mukoki, the Indian, saw you. It is my day, Dupont, and I have waited long—”

The rest Dupont did not hear. For up from the crowd there went a mighty roar. And through it a woman was making her way with outreaching arms—and behind her followed the factor of Lac Bain.

THE FIDDLING MANBreault’s cough was not pleasant to hear. A cough possesses manifold and almost unclassifiable diversities. But there is only one cough when a man has a bullet through his lungs and is measuring his life by minutes, perhaps seconds. Yet Breault, even as he coughed the red stain from his lips, was not afraid. Many times he had found himself in the presence of death, and long ago it had ceased to frighten him. Some day he had expected to come under the black shadow of it himself—not in a quiet and peaceful way, but all at once, with a shock. And the time had come. He knew that he was dying; and he was calm. More than that—in dying he was achieving a triumph. The red-hot death-sting in his lung had given birth to a frightful thought in his sickening brain. The day of his great opportunity was at hand. The hour—the minute.

A last flush of the pale afternoon sun lighted up his black-bearded face as his eyes turned, with their new inspiration, to his sledge. It was a face that one would remember—not pleasantly, perhaps, but as a fixture in a shifting memory of things; a face strong with a brute strength, implacable in its hard lines, emotionless almost, and beyond that, a mystery.

It was the best known face in all that part of the northland which reaches up from Fort McMurray to Lake Athabasca and westward to Fond du Lac and the Wholdais country. For ten years Breault had made that trip twice a year with the northern mails. In all its reaches there was not a cabin he did not know, a face he had not seen, or a name he could not speak; yet there was not a man, woman, or child who welcomed him except for what he brought. But the government had found its faith in him justified. The police at their lonely outposts had come to regard his comings and goings as dependable as day and night. They blessed him for his punctuality, and not one of them missed him when he was gone. A strange man was Breault.

With his back against a tree, where he had propped himself after the first shock of the bullet in his lung, he took a last look at life with a passionless imperturbability. If there was any emotion at all in his face it was one of vindictiveness—an emotion roused by an intense and terrible hatred that in this hour saw the fulfilment of its vengeance. Few men nursed a hatred as Breault had nursed his. And it gave him strength now, when another man would have died.

He measured the distance between himself and the sledge. It was, perhaps, a dozen paces. The dogs were still standing, tangled a little in their traces,—eight of them,—wide-chested, thin at the groins, a wolfish horde, built for endurance and speed. On the sledge was a quarter of a ton of his Majesty’s mail. Toward this Breault began to creep slowly and with great pain. A hand inside of him seemed crushing the fiber of his lung, so that the blood oozed out of his mouth. When he reached the sledge there were many red patches in the snow behind him. He opened with considerable difficulty a small dunnage sack, and after fumbling a bit took there-from a pencil attached to a long red string, and a soiled envelope.

For the first time a change came upon his countenance—a ghastly smile. And above his hissing breath, that gushed between his lips with the sound of air pumped through the fine mesh of a colander, there rose a still more ghastly croak of exultation and of triumph. Laboriously he wrote. A few words, and the pencil dropped from his stiffening fingers into the snow. Around his neck he wore a long red scarf held together by a big brass pin, and to this pin he fastened securely the envelope.

This much done,—the mystery of his death solved for those who might some day find him,—the ordinary man would have contented himself by yielding up life’s struggle with as little more physical difficulty as possible. Breault was not ordinary. He was, in his one way, efficiency incarnate. He made space for himself on the sledge, and laid himself out in that space with great care, first taking pains to fasten about his thighs two babiche thongs that were employed at times to steady his freight. Then he ran his left arm through one of the loops of the stout mail-chest. By taking these precautions he was fairly secure in the belief that after he was dead and frozen stiff no amount of rough trailing by the dogs could roll him from the sledge.

In this conjecture he was right. When the starved and exhausted malamutes dragged their silent burden into the Northwest Mounted Police outpost barracks at Crooked Bow twenty-four hours later, an ax and a sapling bar were required to pry Francois Breault from his bier. Previous to this process, however, Sergeant Fitzgerald, in charge at the outpost, took possession of the soiled envelope pinned to Breault’s red scarf. The information it bore was simple, and yet exceedingly definite. Few men in dying as Breault had died could have made the matter easier for the police.

On the envelope he had written:

Jan Thoreau shot me and left me for dead. Have just strength to write this—no more.

Francois Breault.

It was epic—a colossal monument to this man, thought Sergeant Fitzgerald, as they pried the frozen body loose.

To Corporal Blake fell the unpleasant task of going after Jan Thoreau. Unpleasant, because Breault’s starved huskies and frozen body brought with them the worst storm of the winter. In the face of this storm Blake set out, with the Sergeant’s last admonition in his ears:

“Don’t come back, Blake, until you’ve got him, dead or alive.”

That is a simple and efficacious formula in the rank and file of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police. It has made volumes of stirring history, because it means a great deal and has been lived up to. Twice before, the words had been uttered to Blake—in extreme cases. The first time they had taken him for six months into the Barren Lands between Hudson’s Bay and the Great Slave—and he came back with his man; the second time he was gone for nearly a year along the rim of the Arctic—and from there also he came back with his man. Blake was of that sort. A bull-dog, a Nemesis when he was once on the trail, and—like most men of that kind—without a conscience. In the Blue Books of the service he was credited with arduous patrols and unusual exploits. “Put Blake on the trail” meant something, and “He is one of our best men” was a firmly established conviction at departmental headquarters.

Only one man knew Blake as Blake actually lived under his skin—and that was Blake himself. He hunted men and ran them down without mercy—not because he loved the law, but for the reason that he had in him the inherited instincts of the hound. This comparison, if quite true, is none the less unfair to the hound. A hound is a good dog at heart.

In the January storm it may be that the vengeful spirit of Francois Breault set out in company with Corporal Blake to witness the consummation of his vengeance. That first night, as he sat close to his fire in the shelter of a thick spruce timber, Blake felt the unusual and disturbing sensation of a presence somewhere near him. The storm was at its height. He had passed through many storms, but tonight there seemed to be an uncannily concentrated fury in its beating and wailing over the roofs of the forests.

He was physically comfortable. The spruce trees were so dense that the storm did not reach him, and fortune favored him with a good fire and plenty of fuel. But the sensation oppressed him. He could not keep away from him his mental vision of Breault as he had helped to pry him from the sledge—his frozen features, the stiffened fingers, the curious twist of the icy lips that had been almost a grin.

Blake was not superstitious. He was too much a man of iron for that. His soul had lost the plasticity of imagination. But he could not forget Breault’s lips as they had seemed to grin up at him. There was a reason for it. On his last trip down, Breault had said to

Comments (0)