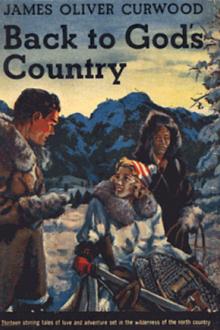

Back to God's Country and Other Stories, James Oliver Curwood [hot novels to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: James Oliver Curwood

- Performer: -

Book online «Back to God's Country and Other Stories, James Oliver Curwood [hot novels to read .TXT] 📗». Author James Oliver Curwood

He drew her back toward the cot, dragging his limb painfully, and seated her again upon the stool. He sat beside her, still holding her hand, patting it, encouraging her. The color was coming back into Marie’s cheeks. Her lips were growing full and red again, and suddenly she gave a trembling little laugh as she looked up into Blake’s face. His presence began to dispel the terror that had possessed her all at once.

“Tell me, Marie.”

He saw the shudder that passed through her slim shoulders.

“They had a fight—here—in this cabin—three days ago,” she confessed. “It must have been—the day—he was killed.”

Blake knew the wild thought that was in her heart as she watched him. The muscles of his jaws tightened. His shoulders grew tense. He looked over her head as if he, too, saw something beyond the cabin walls. It was Marie’s hand that gripped his now, and her voice, panting almost, was filled with an agonized protest.

“No, no, no—it was not Jan,” she moaned. “It was not Jan who killed him!”

“Hush!” said Blake.

He looked about him as if there was a chance that someone might hear the fatal words she had spoken. It was a splendid bit of acting, almost unconscious, and tremendously effective. The expression in his face stabbed to her heart like a cold knife. Convulsively her fingers clutched more tightly at his hands. He might as well have spoken the words: “It was Jan, then, who killed Francois Breault!”

Instead of that he said:

“You must tell me everything, Marie. How did it happen? Why did they fight? And why has Jan gone away so soon after the killing? For Jan’s sake, you must tell me—everything.”

He waited. It seemed to him that he could hear the fighting struggle in Marie’s breast. Then she began, brokenly, a little at a time, now and then barely whispering the story. It was a woman’s story, and she told it like a woman, from the beginning. Perhaps at one time the rivalry between Jan Thoreau and Francois Breault, and their struggle for her love, had made her heart beat faster and her cheeks flush warm with a woman’s pride of conquest, even though she had loved one and had hated the other. None of that pride was in her voice now, except when she spoke of Jan.

“Yes—like that—children together—we grew up,” she confided. “It was down there at Wollaston Post, in the heart of the big forests, and when I was a baby it was Jan who carried me about on his shoulders. Oui, even then he played the violin. I loved it. I loved Jan—always. Later, when I was seventeen, Francois Breault came.”

She was trembling.

“Jan has told me a little about those days,” lied Blake. “Tell me the rest, Marie.”

“I—I knew I was going to be Jan’s wife,” she went on, the hands she had withdrawn from his twisting nervously in her lap. “We both knew. And yet—he had not spoken—he had not been definite. Oo-oo, do you understand, M’sieu Duval? It was my fault at the beginning! Francois Breault loved me. And so—I played with him—only a little, m’sieu!—to frighten Jan into the thought that he might lose me. I did not know what I was doing. No—no; I didn’t understand.

“Jan and I were married, and on the day Jan saw the missioner—a week before we were made man and wife—Francois Beault came in from the trail to see me, and I confessed to him, and asked his forgiveness. We were alone. And he—Francois Breault—was like a madman.”

She was panting. Her hands were clenched. “If Jan hadn’t heard my cries, and come just in time—” she breathed.

Her blazing eyes looked up into Blake’s face. He understood, and nodded.

“And it was like that—again—three days ago,” she continued. “I hadn’t seen Breault in two years—two years ago down at Wollaston Post. And he was mad. Yes, he must have been mad when he came three days ago. I don’t know that he came so much for me as it was to kill Jan, He said it was Jan. Ugh, and it was here—in the cabin—that they fought!”

“And Jan—punished him,” said Blake in a low voice.

Again the convulsive shudder swept through Marie’s shoulders.

“It was strange—what happened, m’sieu. I was going to shoot. Yes, I would have shot him when the chance came. But all at once Francois Breault sprang back to the door, and he cried: ‘Jan Thoreau, I am mad—mad! Great God, what have I done?’ Yes, he said that, m’sieu, those very words—and then he was gone.”

“And that same day—a little later—Jan went away from the cabin, and was gone a long time,” whispered Blake. “Was it not so, Marie?”

“Yes; he went to his trap-line, m’sieu.”

For the first time Blake made a movement. He took her face boldly between his two hands, and turned it so that her staring eyes were looking straight into his own. Every fiber in his body was trembling with the thrill of his monstrous triumph. “My dear little girl, I must tell you the truth,” he said. “Your husband, Jan, did not go to his trap-line three days ago. He followed Francois Breault, and killed him. And I am not John Duval. I am Corporal Blake of the Mounted Police, and I have come to get Jan, that he may be hanged by the neck until he is dead for his crime. I came for that. But I have changed my mind. I have seen you, and for you I would give even a murderer his life. Do you understand? For YOU—YOU—YOU—”

And then came the grand finale, just as he had planned it. His words had stupefied her. She made no movement, no sound—only her great eyes seemed alive. And suddenly he swept her into his arms with the wild passion of a beast. How long she lay against his breast, his arms crushing her, his hot lips on her face, she did not know.

The world had grown suddenly dark. But in that darkness she heard his voice; and what it was saying roused her at last from the deadliness of her stupor. She strained against him, and with a wild cry broke from his arms, and staggered across the cabin floor to the door of her bedroom. Blake did not pursue her. He let the darkness of that room shut her in. He had told her—and she understood.

He shrugged his shoulders as he rose to his feet. Quite calmly, in spite of the wild rush of blood through his body, he went to the cabin door, opened it, and looked out into the night. It was full of stars, and quiet.

It was quiet in that inner room, too—so quiet that one might fancy he could hear the beating of a heart. Marie had flung herself in the farthest corner, beyond the bed. And there her hand had touched something. It was cold—the chill of steel. She could almost have screamed, in the mighty reaction that swept through her like an electric shock. But her lips were dumb and her hand clutched tighter at the cold thing.

She drew it toward her inch by inch, and leveled it across the bed. It was Jan’s goose-gun, loaded with buck-shot. There was a single metallic click as she drew the hammer back. In the doorway, looking at the stars, Blake did not hear.

Marie waited. She was not reasoning things now, except that in the outer room there was a serpent that she must kill. She would kill him as he came between her and the light; then she would follow over Jan’s trail, overtake him somewhere, and they would flee together. Of that much she thought ahead. But chiefly her mind, her eyes, her brain, her whole being, were concentrated on the twelve-inch opening between the bedroom door and the outer room. The serpent would soon appear there. And then—

She heard the cabin door close, and Blake’s footsteps approaching. Her body did not tremble now. Her forefinger was steady on the trigger. She held her breath—and waited. Blake came to the deadline and stopped. She could see one arm and a part of his shoulder. But that was not enough. Another half step—six inches—four even, and she would fire. Her heart pounded like a tiny hammer in her breast.

And then the very life in her body seemed to stand still. The cabin door had opened suddenly, and someone had entered. In that moment she would have fired, for she knew that it must be Jan who had returned. But Blake had moved. And now, with her finger on the trigger, she heard his cry of amazement:

“Sergeant Fitzgerald!”

“Yes. Put up your gun, Corporal. Have you got Jan Thoreau?”

“He—is gone.”

“That is lucky for us.” It was the stranger’s voice, filled with a great relief. “I have traveled fast to overtake you. Matao, the halfbreed, was stabbed in a quarrel soon after you left; and before he died he confessed to killing Breault. The evidence is conclusive. Ugh, but this fire is good! Anybody at home?”

“Yes,” said Blake slowly. “Mrs. Thoreau—is—at home.”

L’ANGE

She stood in the doorway of a log cabin that was overgrown with woodvine and mellow with the dull red glow of the climbing bakneesh, with the warmth of the late summer sun falling upon her bare head. Cummins’ shout had brought her to the door when we were still half a rifle shot down the river; a second shout, close to shore, brought her running down toward me. In that first view that I had of her, I called her beautiful. It was chiefly, I believe, because of her splendid hair. John Cummins’ shout of homecoming had caught her with it undone, and she greeted us with the dark and lustrous masses of it sweeping about her shoulders and down to her hips. That is, she greeted Cummins, for he had been gone for nearly a month. I busied myself with the canoe for that first half minute or so.

Then it was that I received my introduction and for the first time touched the hand of Melisse Cummins, the Florence Nightingale of several thousand square miles of northern wilderness. I saw, then, that what I had at first taken for our own hothouse variety of beauty was a different thing entirely, a type that would have disappointed many because of its strength and firmness. Her hair was a glory, brown and soft. No woman could have criticized its loveliness. But the flush that I had seen in her face, flower-like at a short distance, was a tan that was almost a man’s tan. Her eyes were of a deep blue and as clear as the sky; but in them, too, there was a strength that was not altogether feminine. There was strength in her face, strength in the poise of her firm neck, strength in every movement of her limbs and body. When she spoke, it was in a voice which, like her hair, was adorable. I had never heard a sweeter voice, and her firm mouth was all at once not only gentle and womanly, but almost girlishly pretty.

I could understand, now, why Melisse Cummins was the heroine of a hundred true tales of the wilderness, and I could understand as well why there was scarcely a cabin or an Indian hut in that ten thousand square miles of wilderness in which she had not, at one time or another, been spoken of as “L’ange Meleese.” And yet, unlike that other “angel” of flesh and blood, Florence Nightingale, the story of Melisse Cummins and her work will live and die with her in that little cabin two hundred miles straight north of civilization.

Comments (0)