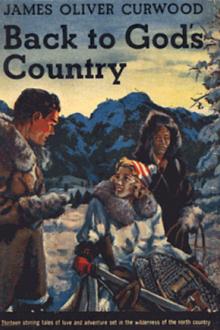

Back to God's Country and Other Stories, James Oliver Curwood [hot novels to read .TXT] 📗

- Author: James Oliver Curwood

- Performer: -

Book online «Back to God's Country and Other Stories, James Oliver Curwood [hot novels to read .TXT] 📗». Author James Oliver Curwood

Marie had changed at the mention of Duval’s name. With the glow in her eyes had come a flush into her cheeks, and Blake could see the strange little quiver at her throat as she looked at him. But she did not see Blake so much as what lay beyond him—Duval’s lonely cabin away up on the edge of the Great Barren, the hours of darkness and agony through which Jan had passed, and the magnificent comradeship of this man who had now dragged himself to their own cabin, half dead.

Many times Jan had told her the story of that terrible winter when Duval had nursed him like a woman, and had almost given up his life as a sacrifice. And this—THIS—was Duval? She bent over him again as he lay on the cot, her eyes shining like stars in the growing dusk. In that dusk she was unconscious of the fact that his fingers had found a long tress of her hair and were clutching it passionately. Remembering Duval as Jan had enshrined him in her heart, she said:

“I have prayed many times that the great God might thank you, m’sieu.”

He raised a hand. For an instant it touched her soft, warm cheek and caressed her hair. Marie did not shrink—yes, that would have been an insult. Even Jan would have said that. For was not this Duval, to whom she owed all the happiness in her life—Duval, more than brother to Jan Thoreau, her husband?

“And you—are Marie?” said Blake.

“Yes, m’sieu, I am Marie.”

A joyous note trembled in her voice as she drew back from the cot. He could hear her swiftly braiding her hair before she struck a match to light the oil lamp hanging from the ceiling. After that, through partly closed eyes, he watched her as she prepared their supper. Occasionally, when she turned toward him as if to speak, he feigned a desire to sleep. It was a catlike watchfulness, filled with his old cunning. In his face there was no sign to betray its hideous significance. Outwardly he had regained his iron-like impassiveness; but in his body and his brain every nerve and fiber was consumed by a monstrous desire—a desire for this woman, the murderer’s wife. It was as strange and as sudden as the death that had come to Francois Breault.

The moment he had looked up into her face in the doorway, it had overwhelmed him. And now even the sound of her footsteps on the floor filled him with an exquisite exultation. It was more than exultation. It was a feeling of POSSESSION.

In the hollow of his hand he—Blake, the man-hunter—held the fate of this woman. She was the Fiddler’s wife—and the Fiddler was a murderer.

Marie heard the sudden deep breath that forced itself from his lips, a gasp that would have been a cry of triumph if he had given it voice.

“You are in pain, m’sieu,” she exclaimed, turning toward him quickly.

“A little,” he said, smiling at her. “Will you help me to sit up, Marie?”

He saw ahead of him another and more thrilling game than the man-hunt now. And Marie, unsuspicious, put her arms about the shoulders of the Pharisee and helped him to rise. They ate their supper with a narrow table between them. If there had been a doubt in Blake’s mind before that, the half hour in which she sat facing him dispelled it utterly. At first the amazing beauty of Thoreau’s wife had impinged itself upon his senses with something of a shock. But he was cool now. He was again master of his old cunning. Pitilessly and without conscience, he was marshaling the crafty forces of his brute nature for this new and more thrilling fight—the fight for a woman.

That in representing the Law he was pledged to virtue as well as order had never entered into his code of life. To him the Law was force—power. It had exalted him. It had forged an iron mask over the face of his savagery. And it was the savage that was dominant in him now. He saw in Marie’s dark eyes a great love—love for a murderer.

It was not his thought that he might alienate that. For that look, turned upon himself, he would have sacrificed his whole world as it had previously existed. He was scheming beyond that impossibility, measuring her even as he called himself Duval, counting—not his chances of success, but the length of time it would take him to succeed.

He had never failed. A man had never beaten him. A woman had never tricked him. And he granted no possibility of failure now. But—HOW? That was the question that writhed and twisted itself in his brain even as he smiled at her over the table and told her of the black days of Jan’s sickness up on the edge of the Barren.

And then it came to him—all at once. Marie did not see. She did not FEEL. She had no suspicion of this loyal friend of her husband’s.

Blake’s heart pounded triumphant. He hobbled back to the cot, leaning on Marie slim shoulder; and as he hobbled he told her how he had helped Jan into his cabin in just this same way, and how at the end Jan had collapsed—just as he collapsed when he came to the cot. He pulled Marie down with him—accidentally. His lips touched her head. He laughed.

For a few moments he was like a drunken man in his new joy. Willingly he would have gambled his life on his chance of winning. But confidence displaced none of his cunning. He rubbed his hands and said:

“Gawd, but won’t it be a surprise for Jan? I told him that some day I’d come. I told him!”

It would be a tremendous joke—this surprise he had in store for Jan. He chuckled over it again and again as Marie went about her work; and Marie’s face flushed and her eyes were bright and she laughed softly at this great love which Duval betrayed for her husband. No; even the loss of his dogs and his outfit couldn’t spoil his pleasure! Why should it? He could get other dogs and another outfit—but it had been three years since he had seen Jan Thoreau! When Marie had finished her work he put his hand suddenly to his eyes and said:

“Peste! but last night’s storm must have hurt my eyes. The light blinds them, ma cheri. Will you put it out, and sit down near me, so that I can see you as you talk, and tell me all that has happened to Jan Thoreau since that winter three years ago?”

She put out the light, and threw open the door of the box-stove. In the dim firelight she sat on a stool beside Blake’s cot. Her faith in him was like that of a child. She was twenty-two. Blake was fifteen years older. She felt the immense superiority of his age.

This man, you must understand, had been more than a brother to Jan. He had been a father. He had risked his life. He had saved him from death. And Marie, as she sat at his side, did not think of him as a young man—thirty-seven. She talked to him as she might have talked to an elder brother of Jan’s, and with something like the same reverence in her voice.

It was unfortunate—for her—that Jan had loved Duval, and that he had never tired of telling her about him. And now, when Blake’s caution warned him to lie no more about the days of plague in Duval’s cabin, she told him—as he had asked her—about herself and Jan; how they had lived during the last three years, the important things that had happened to them, and what they were looking forward to. He caught the low note of happiness that ran through her voice; and with a laugh, a laugh that sounded real and wholesome, he put out his hand in the darkness—for the fire had burned itself low—and stroked her hair. She did not shrink from the caress. He was happy because THEY were happy. That was her thought! And Blake did not go too far.

She went on, telling Jan’s life away, betraying him In her happiness, crucifying him in her faith. Blake knew that she was telling the truth. She did not know that Jan had killed Francois Breault, and she believed that he would surely return—in three days. And the way he had left her that morning! Yes, she confided even that to this big brother of Jan, her cheeks flushing hotly in the darkness—how he had hated to go, and held her a long time in his arms before he tore himself away.

Had he taken his fiddle along with him? Yes—always that. Next to herself he loved his violin. Oo-oo—no, no—she was not jealous of the violin! Blake laughed—such a big, healthy, happy laugh, with an odd tremble in it. He stroked her hair again, and his fingers lay for an instant against her warm cheek.

And then, quite casually, he played his second big card.

“A man was found dead on the trail yesterday,” he said. “Some one killed him. He had a bullet through his lung. He was the mail-runner, Francois Breault.”

It was then, when he said that Breault had been murdered, that Blake’s hand touched Marie’s cheek and fell to her shoulder. It was too dark in the cabin to see. But under his hand he felt her grow suddenly rigid, and for a moment or two she seemed to stop breathing. In the gloom Blake’s lips were smiling. He had struck, and he needed no light to see the effect.

“Francois—Breault!” he heard her breathe at last, as if she was fighting to keep something from choking her. “Francois Breault—dead—killed by someone—”

She rose slowly. His eyes followed her, a shadow in the gloom as she moved toward the stove. He heard her strike a match, and when she turned toward him again in the light of the oil-lamp, her face was pale and her eyes were big and staring. He swung himself to the edge of the cot, his pulse beating with the savage thrill of the inquisitor. Yet he knew that it was not quite time for him to disclose himself—not quite. He did not dread the moment when he would rise and tell her that he was not injured, and that he was not M’sieu Duval, but Corporal Blake of the Royal Mounted Police. He was eager for that moment. But he waited—discreetly. When the trap was sprung there would be no escape.

“You are sure—it was Francois Breault?” she said at last.

He nodded.

“Yes, the mail-runner. You knew him?”

She had moved to the table, and her hand was gripping the edge of it. For a space she did not answer him, but seemed to be looking somewhere through the cabin walls—a long way off. Ferret-like, he was watching her, and saw his opportunity. How splendidly fate was playing his way!

He rose to his feet and hobbled painfully to her, a splendid hypocrite, a magnificent dissembler. He seized her hand and held it in both his own. It was small and soft, but strangely cold.

“Ma cheri—my dear child—what makes you look like that? What has the death of Francois Breault to do with you—you and Jan?”

It was the voice of a friend, a brother, low, sympathetic, filled just enough with anxiety. Only last winter, in just that way, it had won the confidence and roused the hope of Pierrot’s wife, over on the Athabasca. In the summer that followed they hanged Pierrot. Gently Blake spoke the words again. Marie’s lips trembled. Her great eyes were looking at him—straight into his soul, it seemed.

“You may tell me, ma cheri,”

Comments (0)