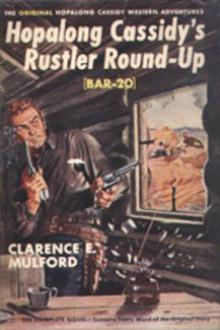

The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Book online «The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗». Author Clarence E. Mulford

Slipping on the treacherous malpais and loose stones, fighting through the torturing locust and cactus hidden in the grass, he pushed through matted thickets of oak brush and manzanito by main strength, savagely determined to gain his goal well in advance of the creeping, cautious cattle-thieves who crept, foot by foot, down the canyon on the other side of the butte.

A black bear lumbered out of his way and sat down to watch him pass, the little eyes curious and unblinking. Several white-tailed deer shot up a slope ahead of him in unbelievable leaps and at a remarkable speed. He leaped over a fallen pine trunk and his heavy bootheel crushed a snake which rattled and struck at the same instant; but the heavy boots and the trousers tucked within them made the vicious fangs harmless. Flies swarmed about him and yellowjackets stung him as he squashed over a muddy patch of clay. A grinning coyote slunk aside to give him undisputed right-of-way, while high up on the slope a silver-tip grizzly stopped his foraging long enough to watch him pass.

For noise he cared nothing; the up-flung butte reared its rocky walls between him and his enemies; and he plunged on, all his energies centered on speed, regardless of the stings and the sweat which streamed down him, tinged with blood from the mass of smarting scratches. Malpais, cunningly hidden in the grass, pressed painfully against the worn, thin soles of his boots and hurt him cruelly as he slipped and floundered. He staggered and slipped more frequently now, and the pack on his back seemed to have trebled in weight; his breath came in great, sobbing gulps and the blood pulsed through his aching temples like hammer blows, while a hot, tight band seemed to encircle his parched throat; but he now was in sight of his goal.

Beginning at a rock slide, a mass of treacherous broken rock and shale in which he sank to his ankles at every plunging step, a faint zigzag line wandered up the southern face of the butte. He did not know that it could be mastered, but he did not have time to gain the easier trail, up which he had led his horse. Struggling up the shale slope, slipping and floundering in the treacherous footing, he flung himself on the rock ledge which slanted sharply upward.

Resting until his head cleared, he began a climb which ever after existed in his memory as a vague but horrible nightmare. Rattlesnakes basked in the sun, coiling swiftly and sounding their whirring alarm as he neared them; but blindly thrown rocks mashed them and sent them writhing over the edge to whirl to destruction in the valley below. Treacherous, rotten ledges crumbled as he put his weight on them, and he saved himself time and time again only by an intuitive leap nearly as dangerous as the peril he avoided. At many places the ledge disappeared, and it was only by desperate use of fingers and toes that he managed topass the gaps, spread-eagled against the cliff while he moved an inch at a time, high above the yawning depths, to the beginning of a new ledge.

Scrawny, hardy shrubs, living precariously in cracks and on ledges, and twisted roots found his grip upon them. At one place a flue-like crack in the wall, a “chimney,” was the only way to proceed, and he climbed it, back and head against one side, knees and hands against the other, the strain making him faint and dizzy. Below him lay the treetops, dwarfed, a blur to his throbbing eyes.

A ledge of rock upon which he momentarily rested his weight detached itself and plunged downward a sheer three hundred feet, crashing through the underbrush and scrub timber before it burst apart. On hands and knees he crossed a muddy spot, where a thin trickle of water, no wider than his thumb, spread out and made the ledge slippery before it was sucked in by the sun-baked rocks. A swarm of yellowjackets, balancing daintily on the wet rock, attacked him viciously when he disturbed them. He struck at them blindly, instinctively shielding his eyes, and arose to his feet as he groped onward.

The pack on his back, aside from its weight, was a thing of danger, for several times it thrust against the wall and lost him his balance, threatening him with instant destruction; but each time he managed to save himself by a frantic twist and plunge to his hands and knees, clawing at the precarious footing with fingers and toes.

At one place he lay prostrate for several minutes before his will, shaking off the lethargy which numbed him, sent him on again. And the spur which awakened his dulled senses proved that his frantic haste was justified; for a sharp, venomous whine overhead was followed by the flat impact of lead on rock, and a handful of shale and small bits of stone showered down upon him. The faint, whip-like report in the valley did not penetrate his roaring ears, for now all he could think of was the edge of the butte fifty feet above him.

Never had such a distance seemed so great, so impossible to master. It seemed as though ages passed before he clawed at the rim and flung himself over it in one great, despairing effort and fell, face down and sprawling, upon the carpet of grass and flowers. Down in the valley the persistent reports ceased, but he did not know it; and an hour passed before he sat up and looked around, dazed and faint. Arising, he staggered to the pool where Pepper waited for him at the end of her taut picket rope.

The water was bitter from concentration, but it tasted sweeter to him than anything he ever had drunk-He dashed it over his face, unmindful of the increased smarting of the stings and scratches. Resting a few minutes, he went to the top of the easier trail, up which he had led the horse, and saw a man creeping along it near the bottom; but the rustler fled for shelter when Johnny’s Sharp’s suggested that the trail led to sudden death.

Having served the notice he lay quietly resting and watching. The heat of the canyon was gone and he reveled in the crisp coolness of the breeze which fanned him. As he rested he considered the situation, and found it good He was certain that no man would be fool enough to attempt the way he had come while an enemy occupied the top of the butte; the trail up the north side could easily be defended; the other Twin, easy rifle range away, was lower than the one he occupied and would not be much of a menace if he were careful; he had water in plenty, food and ammunition for two weeks, and there was plenty of water and grass for the horse.

Safe as the butte was, he cheerfully damned the necessity which had driven him out of the canyon: the question of sleep. Dodging and outwitting four men during his waking hours would not have been an impossible task; but it only would have been a matter of time before they would have caught him asleep and helpless.

Returning to the pool, he saw how closely Pepper had cropped the grass within the radius of the picket rope, changed the stake and then built a fire, worrying about the scarcity of fuel. Since he could not afford to waste the wood he cooked a three-days supply of food.

Eating a hearty meal, he made mud-plasters and applied them to the swollen stings, binding them in place by strips torn from an undershirt, and then he sought the shade of the ledge by the pool for a short sleep, which he would have to snatch at odd times during the day so as to be awake all night, which would be the time of greatest danger.

IT WAS late in the afternoon when he awakened from a sleep which had been sound despite the stings. Removing the plasters he made a tour of the plateau, satisfying himself that there was really only one way up and that the rustlers were not trying to get to him. Returning to the camp, he filled a hollow in the rock floor with water, bathed, put on his other change of clothes, and then made a supper of cold beans and bacon’ Filling another hollow, he pushed his soiled clothes in it to soak over night.

When he passed a break in the rampart-like wall near the top of the trail, which at that point shot up several feet above the top of the butte, a bullet screamed past his head, so close that he felt the wind of it. Peering cautiously across the canyon he saw a thin cloud of smoke lazily rising over the top of a huge, black lava bowlder on the crest of the other butte. A head was just disappearing and he jerked his rifle to his shoulder and fired.

“Five hundred an’ a little more,” he muttered. “I got it now, you wall-eyed thief!”

Another puff of smoke burst out from the lower edge of the lava bowlder, the bullet striking the rampart below him. His reply was instantaneous, and was directed at a light spot which ducked instantly out of sight, just a little too quickly to be hit by the bullet, which tossed a fine spray of dust into the air and put a leaden streak where the face had been. He fired again, this time at the other side of the bowlder, where he thought he saw another moving white spot, and he thought right.

After a quick glance down the trail, Johnny took a position a hundred yards to the left, trying to find a place where he could catch a glimpse of the hostile marksman. But Fleming had a torn and bloody ear and a great respect for the man on the southern Twin, and henceforth became wedded to caution. Curiosity was all very well, but his was thoroughly satisfied, and discretion meant a longer life of sinful activities.

“I had my look, three of ‘em,” growled Fleming. “An’ three looks are enough for any man,” he added quizzically, binding up his bloody ear with a soiled and faded neckerchief, which should have given him blood-poisoning, but did not.

“Now that we got him treed, there ain’t no use goin’ on th’ rampage an’ gettin’ all shot up tryin’ to get him. All we got to do is wait, an’ get him when he has to come down. It’ll be plumb easy when he makes his break. A man like him is too cussed handy with his gun for anybody to go an I get reckless with. If we keep one man near th’ bottom of that trail, he’s our meat. I don’t know how he ever got up that scratch on th’ wall; but I’ll bet there ain’t a man livin’ that can go down it.”

Johnny grew tired of watching for Fleming, and wriggling back to where he could safely get on his feet he arose and made the rounds again. When he reached the place where he had floundered over the edge to safety he critically examined the faint trail from cover, and the more he saw of it the more he regarded his ascent as a miracle.

“Only a fool would ‘a’ tried it,” he grinned. “It’s somethin’ a man can do once in a hundred times; only he’s got to make it th’ very

Comments (0)