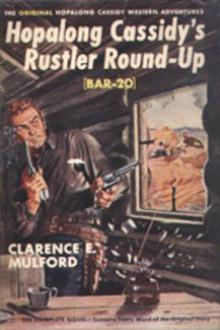

The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Book online «The Man From Bar-20, Clarence E. Mulford [distant reading TXT] 📗». Author Clarence E. Mulford

Deep curses roared from the canyon and several flashes of flame darted out.

“Lay on yore stummicks, fightin’ mosquitoes, an’ heavin I wood on that fire at long range, huh?” jeered

Johnny, throwing another rock. “These are better at night than cartridges, an’ they won’t run out. I’ll give you some real troubles. I only wish I had a bag of yellowjackets to drop!”

Another jet of flame stabbed upward, but from a new place, farther back; and a voice full of wrath and pain described the man on the butte, and with a fertile imagination.

“What’s th’ matter with you? An’ what’s all th’ hellaballoo?” indignantly demanded another and more distant voice. “How can a man sleep in such a blasted uproar?”

“Shut up! “roared Purdy with heat. “Who carea whether you sleep or not? He cut my head an’ near busted my arm with his d–-d rocks! Mebby you think they ain’t makin’ good time when they get down here! Only hope he stumbles an’ follers ‘em!”

“He’s a lucky fool,” commented Fleming, serene in the security of his new position. “Luckiest dog I ever saw.”

“Lucky!” snorted Purdy. “Lucky! Anybody else would ‘a’ been picked clean by th’ ki-yotes before now. For a cussed fool playin’ a lone hand he’s doin’ real well. But we got th’ buzzard where we want him!”

“Lone hand nothin’,” grunted Fleming. “Didn’t he have that drunken Long Pete helpin’ him?”

Purdy growled in his throat and gently rubbed his numbed arm. “There’s another. It just missed th’ fire. Say! Thafs what he’s aimin’ at! “

“Mebby he is,” snorted Fleming; “but if he is he’s got a cussed bad aim. Judgin’ from where they landed, I bets he was aimin’ ‘em all at me. I got four bits that says he wasn’t aimin’ at no fire when he thrun them little ones. One of ‘em come so close to my head that I could hear th’ white-winged angels a-singin’.”

“‘White-winged angels a-singin’!’ “snorted Purdy. “H—I of a chance you’ll ever have of hearin’ white angels sing. Yore spiritual ears’ll hear steam a-sizzlin’, an’ th’ moans of th’ damned; an’ yore spiritual red nose will smell sulphur till th’ stars drop out.”

“I’m backin’ Purdy,” said the distant voice. “They don’t let no skunk perfume get past th’ Golden Gates.”

“They won’t let any of you in hell,” jeered a clear voice from above.;< You’ll swing between th’ two worlds like pendulums in eternity. Cow-thieves are barred.”

A profane duet was his answer, and he listened closely as Holbrook’s voice was heard. “Say!” he growled, killing mosquitoes with both hands and sitting up behind his bowlder. “Can’t you hold yore powwow somewhere else? Want him to heave rocks all night? How can I sleep with all that racket goin’ on? Yo’re near as bad as these singin’ blood-suckers; an’ who was it that kicked me in th’ ribs just now?”

“If you wouldn’t sprawl out in a natural path an’ take up th’ earth you wouldn’t get kicked in th’ ribs!” snapped Fleming.

“Yo’re a fine pair of doodle-bugs,” sneered Hoibrook, sighing wearily as he arose. He lowered his voice. “Here he is over this end of th’ trail an’ givin’ you a fine chance to sneak up an’ bushwhack him; an’ all you do is dodge rocks, cuss yore fool luck, an’ kick folks in th’ ribs. Don’t you know an opportunity when you see one?”

“Is this an opportunity?” mumbled Purdy sarcastically, rubbing his arm and fighting mosquitoes.

“With that fire showing up everything for rods?” softly asked Fleming with heavy irony. “Who’s been puttin’ loco weed in yore grub?”

“‘Tain’t loco weed,” growled Purdy. “It’s redeye. He drinks it like it was water.”

“No such luck,” retorted Holbrook; “not while yo’re around. It ain’t no opportunity if yo’re aimin’ to have a pe-rade past th’ fire,” he continued in a harsh whisper; “but it shore was a good one if you had cut down through th’ canyon a couple of rods below th’ end of th’ trail, an’ then climbed up to it an’ stuck close to th’ wall. You could ‘a’ been up there now, a-layin’ for him when he went back on guard. It’s cussed near as simple as you are.”

“You must ‘a’ read that in that joke book what come with th’ last bottle of liniment,” derided Purdy. “Fine, healthy target a man would make if he didn’t get over th’ top in time! Lovely job! You must think he’s a fool.”

“Don’t be too sarcastic with him, Purdy,” chuckled Fleming. “He does real well for a man that thinks with his feet.”

“You fellers make me tired!” muttered Holbrook in sudden decision as another rock flew into pieces on a bowlder and rattled through the brush. “I’d just as soon get shot on a good gamble as die from these whinin’ leeches. I’m all bumps, an’ every bump itches like blazes. I never thought there was so many of ‘em on earth. You watch me go up there an’ covef me if you can. Jeer at him an’ keep him up there heavin’ rocks as long as you can.”

“Watch you?” grunted Purdy. “That’s just what I’m aimin’ to do. I’m aimin’ to watch you do it. We don’t have to take chances like that. His grub will run out an’ make him come down. Time is no object to us. We can afford to wait.”

“You can’t do it, Frank,” said Fleming, dogmatically, ducking low as another rock smashed itself to pieces against a bowlder.

“Huh!” snorted Holbrook, picking up his rifle and departing.

His friends chose their positions judiciously and shouted insults at the man on the butte; and after a few minutes they saw Holbrook, bent double, dart swiftly across a little open space, disappear into the brush and emerge into sight again, vague and shadowy, near the base of the wall a dozen yards below the end of the trail. He crept slowly over a patch of detritus which sloped up to the wall, and began his climb, which was not as easy a task as he had believed.

The wall, eroded where rotting stone had crumbled away in layers, was a series of curving bulges, each capped by and ending in an out-thrust ledge. He forsook his rifle on the second ledge and went slowly, doggedly upward, but despite all his care to make no noise, he dislodged pebbles and chunks of rotten stone and shale which lay thick upon the rocky shelves. When half way up he paused to search out hand and foot holds and became suddenly enraged at the amount of time he was consuming; and he realized, uneasily, that he had heard no more crashing rocks. The knowledge sent caution to the winds and drove him at top speed, and it also robbed him of some of the jaunty assurance which had urged him to his task. Fear of the ridicule and the jeers of his sarcastic friends now became a more compelling motive than the hope of success; and he writhed and stretched, twisted, clawed, and scrambled upward with an angry, savage determination which he would have characterized as “bullheaded” in anyone else. Then another smashing rock revived his hopes and made him strain with renewed strength.

At last his fingers gripped the crumbling sandstone of the trail’s edge and by a fine display of strength and agility he swung himself over it and rolled swiftly across the slanting ledge to the base of the wall, where he arose to his feet and leaped up the precarious path. The ascent was twelve hundred feet long and it swept upward at a grade which defied anyone to dash along it for any distance. Walking rapidly would have taxed to the utmost a man in the pink of condition; and his pedal exercise for years had been mostly confined to walking to his horse.

The footing was far from satisfactory and demanded close scrutiny in daylight, while in the dark it was a desperate gamble except when attempted at a snail’s pace. Ridges, crevices, stones, pebbles, drifts of shale and rotten stone, treacherous in their obedience to the law of gravity when the pressure of a foot started them sliding toward the edge of the abyss; places where the soft sandstone had split in great masses and dropped into the canyon, taking parts of the trail with them and leaving only broken, narrow ledges of the same rotten stone, all these conspired to make him use up precious minutes.

Below him to his right lay a sheer drop of two hundred feet; above him towered the massive wall; behind him and unable to help him, were his friends, and the fire, which was not bright enough to let him see the footing, but too bright for his safety in another way; before him stretched the heart-breaking trail, steep, seemingly interminable, leading to the top of the butte, where the silence was ominous, for somewhere up there was an expert shot defending his life. He had heard no more crashing rocks, and the insults of his friends had not been answered; and to hear such an answer or the crash of a rock he would have given his season’s profits.

He paused for breath more frequently with each passing minute and his feet were like weights of lead, the muscles in his legs aching and nearly unresponsive. He was paying for the speed he had made in the beginning.

The great wall curved slightly outward now and he hugged it closely as he groped onward, and soon emerged from its shadow to become silhouetted against the fire below. And then a spurt of flame split the darkness above him and a shriek passed over his head and died out below as the roar of the heavy rifle awoke crashing echoes in the canyon.

Below him lurid jets of fire split the darkness and singing lead winged through the air with venomous whines, which arose to a high pitch as they passed him and died out in the sky. He knew that his friends were firing well away from the wall, but he cursed them for the mistakes they might make. Another flash blazed above him, and the sound of the lead and the roar of the gun told him that his enemy was now using a Colt. Ordinarily this would have given him a certain amount of satisfaction, for everyone knows that while a rifle is effective at such a range, a hit with a revolver is largely a matter of luck; but as he leaped back into a handy recess a second bullet from the Colt struck the generous slack of his trousers and burned a welt on that portion of his anatomy where sitting in a saddle would irritate the most. It was a lucky shot, but Holbrook was too much of a pessimist at that moment to derive any satisfaction from the knowledge.

“I’m in a h—l of a pickle!” he growled as the shadows of the recess folded about him. “I can’t go up, an’ I can’t go down I can’t even sit down. I got to wait till that fire dies out an’ suppose they don’t let it die? Five minutes more an’ I would have won out.”

“Hey, Frank! Are you all right?” asked

Comments (0)