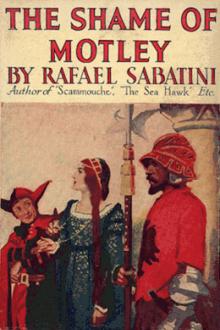

The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

Well, well, it were better she should know the truth at once, and choose such a demeanour as she considered fitting towards a Fool. I had no stomach for the courtesies that were meant for such a man as I was not.

“Madonna, you are in error,” I informed her, speaking slowly. “This garb is no travesty. It is my usual raiment.”

There was a pause and I saw the slackening of her reins. No doubt, had we been afoot she would have halted, the better to confront me.

“How?” she asked, and a new note, imperious and chill, was sounding already in her voice. “You would not have me understand that you are by trade a Fool?

“Allowing that I am not a fool by birth, under what other circumstances, think you, I should be likely to wear the garments of a Fool?”

“But this morning,” she protested, after a brief pause, “when first I met you, you were not so arrayed.”

“I was arrayed even as I am now, in a cloak and hat and boots that hid my motley from such undiscerning eyes as were yours and your grooms’—all taken up with your own fears as you then were.”

There was in the tail of that a sting, as I meant there should be, for the sudden haughtiness of her tone was cutting into me. Was I less worthy of thanks because I was a Fool? Had I on that account done less to serve and save her? Or was it that the action which, in a spurred and armoured knight, had been accounted noble was deemed unworthy of thanks in a crested, motleyed jester? It seemed, indeed, that some such reasoning she followed, for after that we spoke no more until we were approaching Fano.

A many times before had I felt the shame of my ignoble trade, but never so acutely as at that moment. It had seared my soul when Giovanni Sforza had told my story to his Court, ere he had driven me from Pesaro with threats of hanging, and it had burned even deeper when later, Madonna Lucrezia, upon entrusting me with her letter to her brother, had upbraided me with the supineness that so long had held me in that vile bondage. But deepest of all went now the burning iron of that disgrace. For my companion’s silence seemed to argue that had she known my quality she would have scorned the aid of which she had availed herself to such good purpose. If any doubt of this had mercifully remained me, her next words would have served to have resolved it. It was when the lights of Fano gleamed ahead; we were coming to a cross-roads, and I urged the turning to the left.

“But Fano is in front,” she remonstrated coldly.

“This way we can avoid the town and gain the Pesaro road beyond it,” answered I, my tone as cool as hers.

“Yet may it not be that at Fano I might find an escort?”

I could have cried out at her cruelty, for in her words I could but read my dismissal from her service. There had been no more talk of an escort other than that which I afforded, and with which at first she had been well content.

I sat my mule in silence for a moment. She had been very justly served had I been the vassal that she deemed me, and had I borne myself in that character without consideration of her sex, her station or her years. She had been very justly served had I wheeled about and left her there to make her way to Fano, and thence to Pesaro, as best she might. She was without money, as I knew, and she would have found in Fano such a reception as would have brought the bitter tears of late repentance to her pretty eyes.

But I was soft-hearted, and, so, I reasoned with her; yet in a manner that was to leave her no doubt of the true nature of her situation, and the need to use me with a little courtesy for the sake of what I might yet do, if she lacked the grace to treat me with gratitude for the sake of that which I had done already.

“Madonna,” said I. “It were wiser to choose the by-road and forego the escort, since we have dispensed with it so far. There are many reasons why a lady should not seek to enter Fano at this hour of night.”

“I know of none,” she interrupted me.

“That may well be. Nevertheless they exist.”

“This night-riding in so lonely a fashion is little to my taste,” she told me sullenly. I am for Fano.”

She had the mercy to spare me the actual words, yet her tone told me as plainly as if she had uttered them that I could go with her or not, as I should choose. In silence, very sore at heart, I turned my mule’s head once more towards the lights of the town.

“Since you are resolved, so be it,” was all my answer; and we proceeded.

No word did we exchange until we had entered the main street, when she curtly asked me which was the best inn.

“‘The Golden Fish,’” said I, as curtly, and to “The Golden Fish” we went.

Arrived there, Madonna Paola took affairs into her own hands. She dismounted, leaving the reins with a groom, and entering the common-room she proclaimed her needs to those that occupied it by loudly calling upon the landlord to find her an escort of three or four knaves to accompany her at once to Pesaro, where they should be well rewarded by the Lord Giovanni, her cousin.

I had followed her in, and I ground my teeth at such an egregious piece of folly. Her hood was thrown back, displaying the lenza of fine linen on her sable hair, and over this a net of purest gold all set with jewels. Her camorra, too, was open, and in her girdle there were gems for all to see. There were but a half-dozen men in the room. Two of these had a venerable air—they may have been traders journeying to Milan—whilst a third, who sat apart, was a slender, effeminate-looking youth. The remaining three were fellows of rough aspect, and when one of them—a black-browed ruffian—raised his eyes and fastened them upon the riches that Madonna Paola with such indifference displayed, I knew what was to follow.

He rose upon the instant, and stepping forward, he made her a low bow.

“Illustrious lady,” said he, “if these two friends of mine and I find favour with you, here is an escort ready found. We are stout fellows, and very faithful.”

Faithful to their cut-throat trade, I made no doubt he meant.

His fellows now rose also, and she looked them over, giving herself the airs of having spent her virgin life in judging men by their appearance. It was in vain I tugged her cloak, in vain I murmured the word “wait” under cover of my hand. She there and then engaged them, and bade them make ready to set out at once. One more attempt I made to induce her to alter her resolve.

“Madonna,” said I, “it is an unwise thing to go a-journeying by night with three unknown men, and of such villainous appearance. To me they seem no better than bandits.”

We were standing apart from the others, and she was sipping a cup of spiced wine that the host had mulled for her. She looked at me with a tolerant smile.

“They are poor men,” said she. “Would you have them robed in velvet?”

“My quarrel is with their looks, Madonna, not their garments,” I answered patiently. She laughed lightly, carelessly; even, I thought, a trifle scornfully.

“You are very fanciful,” said she, then added—“but if so be that you are afraid to trust yourself in their company, why then, sir, I need bring you no farther out of the road that you were following when first we met.”

Did the child think that some jealousy actuated me, and prompted me to inspire her with mistrust of my supplanters? She angered me. Yet now, more than ever was I resolved to journey with her. Leave her at the mercy of those ruffians, whom in her ignorance she was mad enough to trust, I could not—not even had she whipped me. She was so young, so frail and slight, that none but a craven could have found it in his heart to have deserted her just then.

“If it please you Madonna,” I answered smoothly, “I will make bold to travel on with you.”

It may be that my even accents stung her; perhaps she read in them some measure of reproof of the ingratitude that lay in her altered bearing towards me. Her eyes met mine across the table, and seemed to harden as she looked. Her answer came in a vastly altered tone.

“Why, if you are bent that way, I shall be glad to have you avail yourself of my escort, Boccadoro.”

I had suffered the scorn now of her speech, now of her silence, for some hours, but never was I so near to turning on her as at that moment; never so near to consigning her to the fate to which her headstrong folly was compelling her. That she should take that tone with me!

The violence of the sudden choler I suppressed turned me pale under her steady glance. So that, seeing it, her own cheeks flamed crimson, and her eyes fell, as if in token that she realised the meanness of her bearing. To some natures there can be nothing more odious than such a realisation, and of those, I think, was she; for she stamped her foot in a sudden pet, and curtly asked the host why there was such delay with the horses.

“They are at the door, Madonna,” he protested, bowing as he spoke. “And your escort is already waiting in the saddle.”

She turned and strode abruptly towards the threshold. Over her shoulder she called to me:

“If you come with us, Boccadoro, you had best be brisk.”

“I follow, Madonna,” said I, with a grim relish, “so soon as I have paid the reckoning.”

She halted and half turned, and I thought I saw a slight droop at the corners of her mouth.

“You are keeping count of what I owe you?” she muttered.

“Aye, Madonna,” I answered, more grimly still, “I am keeping count.” And I thought that my wits were vastly at fault if that account were not to be greatly swelled ere Pesaro was reached. Haply, indeed, my own life might go to swell it. I almost took a relish in that thought. Perhaps then, when I was stiff and cold—done to death in her service—this handsome, ungrateful child would come to see how much discomfort I had suffered for her sake.

My thoughts still ran in that channel as we rode out of Pesaro, for I misliked the way in which those knaves disposed themselves about us. In front went Madonna Paola; and immediately behind her, so that their horses’ heads were on a level with her saddle-bow, one on each side, went two of those ruffians. The third, whom I had heard

Comments (0)