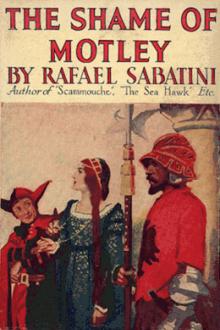

The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

I thought she paled a little, and her brows contracted.

“In God’s name, let us get forward, then!” cried Giacopo. “Orsu! To horse, knaves!”

No second bidding did they need. In the twinkling of an eye they were in the saddle, and one of them had caught the bridle of the leading mule of the litter. Giacopo called to me to lead the way with him, with no more ceremony than if I had been one of themselves. But I made no ado. A chase is an interesting business, whatever your point of view, and if a greater safety lies with the hunter, there is a keener excitement with the hunted.

Down that steep and slippery hillside we blundered, making for Cagli at a pace in which there lay a myriad-fold more danger than could menace us from any party of pursuers. But fear was spur and whip to the unreasoning minds of those poltroons, and so from the danger behind us we fled, and courted a more deadly and certain peril in the fleeing. At first I sought to remonstrate with Giacopo; but he was deaf to the wisdom that I spoke. He turned upon me a face which terror had rendered whiter than its natural habit, white as the egg of a duck, with a hint of blue or green behind it. I had, besides, an ugly impression of teeth and eyeballs.

“Death is behind us, sir,” he snarled. “Let us get on.”

“Death is more assuredly before you,” I answered grimly. “If you will court it, go your way. As for me, I am over-young to break my neck and be left on the mountain-side to fatten crows. I shall follow at my leisure.”

“Gesu!” he cried, through chattering teeth. “Are you a coward, then?”

The taunt would have angered me had his condition been other than it was; but coming from one so possessed of the devil of terror, it did no more than provoke my mirth.

“Come on, then, valiant runagate,” I laughed at him.

And on we went, our horses now plunging, now sliding down yard upon yard of moving snow, snorting and trembling, more reasoning far than these rational animals that bestrode them. Twice did it chance that a man was flung from his saddle, yet I know not what prayers Madonna may have been uttering in her litter, to obtain for us the miracle of reaching the plain with never so much as a broken bone.

Thus far had we come, but no farther, it seemed, was it possible to go. The horses, which by dint of slipping and sliding had encompassed the descent at a good pace, were so winded that we could get no more than an amble out of them, saving mine, which was tolerably fresh.

At this a new terror assailed the timorous Giacopo. His head was ever turned to look behind—unfailing index of a frightened spirit; his eyes were ever on the crest of the hills, expecting at every moment to behold the flash of the pursuers’ steel. The end soon followed. He drew rein and called a halt, sullenly sitting his horse like a man deprived of wit— which is to pay him the compliment of supposing that he ever had wit to be deprived of.

Instantly the curtain-rings rasped, and Madonna Paola’s head appeared, her voice inquiring the reason of this fresh delay.

Sullenly Giacopo moved his horse nearer, and sullenly he answered her.

“Madonna, our horses are done. It is useless to go farther.”

“Useless?” she cried, and I had an instance of how sharply could ring the voice that I had heard so gentle. “Of what do you talk, you knave? Ride on at once.”

“It is vain to ride on,” he answered obdurately, insolence rising in his voice. “Another half-league—another league at most, and we are taken.”

“Cagli is less than a league distant,” she reminded him. “Once there, we can obtain fresh horses. You will not fail me now, Giacopo!”

“There will be delays, perforce, at Cagli,” he reminded her, “and, meanwhile, there are these to guide the Borgia sbirri.” And he pointed to the tracks we were leaving in the snow.

She turned from him, and addressed herself to the other three.

“You will stand by me, my friends,” she cried. “Giacopo, here, is a coward; but you are better men.” They stirred, and one of them was momentarily moved into a faint semblance of valour.

“We will go with you, Madonna,” he exclaimed. “Let Giacopo remain behind, if so he will.”

But Giacopo was a very ill-conditioned rogue; neither true himself, nor tolerant, it seemed, of truth in others.

“You will be hanged for your pains when you are caught!” he exclaimed, “as caught you will be, and within the hour. If you would save your necks, stay here and make surrender.”

His speech was not without effect upon them, beholding which, Madonna leapt from the litter, the better to confront them. The corners of her sensitive little mouth were quivering now with the emotion that possessed her, and on her eyes there was a film of tears.

“You cowards!” she blazed at them, “you hinds, that lack the spirit even to run! Were I asking you to stand and fight in defence of me, you could not show yourselves more palsied. I was a fool,” she sobbed, stamping her foot so that the snow squelched under it. “I was a fool to entrust myself to you.”

“Madonna,” answered one of them, “if flight could still avail us, you should not find us stubborn. But it were useless. I tell you again, Madonna, that when I espied them from the hill-top yonder, they were but a half-league behind. Soon we shall have them over the mountain, and we shall be seen.”

“Fool!” she cried, “a half-league behind, you say; and you forget that we were on the summit, and they had yet to scale it. If you but press on we shall treble that distance, at least, ere they begin the descent. Besides, Giacopo,” she added, turning again to the leader, “you may be at fault; you may be scared by a shadow; you may be wrong in accounting them our pursuers.”

The man shrugged his shoulders, shook his head, and grunted.

“Arnaldo, there, made no mistake. He told us what he saw.”

“Now Heaven help a poor, deserted maid, who set her trust in curs!” she exclaimed, between grief and anger.

I had been no better than those hinds of hers had I remained unmoved. I have said that I hated the very name of Sforza; but what had this tender child to do with my wrongs that she should be brought within the compass of that hatred? I had inferred that her pursuers were of the House of Borgia, and in a flash it came to me that were I so inclined I might prove, by virtue of the ring I carried, the one man in Italy to serve her in this extremity. And to be of service to her, her winsome beauty had already inflamed me. For there was I know not what about this child that seemed to take me in its toils, and so wrought upon me that there and then I would have risked my life in her good service. Oh, you may laugh who read. Indeed, deep down in my heart I laughed myself, I think, at the heroics to which I was yielding—I, the Fool, most base of lacqueys—over a damsel of the noble House of Santafior. It was shame of my motley, maybe, that caused me to draw my cloak more tightly about me as I urged forward my horse, until I had come into their midst.

“Lady,” said I bluntly and without preamble, “can I assist you? I have inferred your case from what I have overheard.”

All eyes were on me, gaping with surprise—hers no less than her grooms’.

“What can you do alone, sir?” she asked, her gentle glance upraised to mine.

“If, as I gather, your pursuers are servants of the House of Borgia, I may do something.”

“They are,” she answered, without hesitation, some eagerness, even, investing her tones.

It may seem an odd thing that this lady should so readily have taken a stranger into her confidence. Yet reflect upon the parlous condition in which she found herself. Deserted by her dispirited grooms, her enemies hot upon her heels, she was in no case to trifle with assistance, or to despise an offer of services, however frail it might seem. With both hands she clutched at the slender hope I brought her in the hour of her despair.

“Sir,” she cried, “if indeed it lies in your power to help me, you could not find it in your heart to be sparing of that power did you but know the details of my sorry circumstance.”

“That power, Madonna, it may be that I have,” said I, and at those words of mine her servants seemed to honour me with a greater interest. They leaned forward on their horses and eyed me with eyes grown of a sudden hopeful. “And,” I continued, “if you will have utter faith in me, I see a way to render doubly certain your escape.”

She looked up into my face, and what she saw there may have reassured her that I promised no more than I could accomplish. For the rest she had to choose between trusting me and suffering capture.

“Sir,” said she, “I do not know you, nor why you should interest yourself in the concerns of a desolated woman. But, Heaven knows, I am in no case to stand pondering the aid you offer, nor, indeed, do I doubt the good faith that moves you. Let me hear, sir, how you would propose to serve me.”

“Whence are you?” I inquired.

“From Rome,” she informed me without hesitation, “to seek at my cousin’s Court of Pesaro shelter from a persecution to which the Borgia family is submitting me.”

At her cousin’s Court of Pesaro! An odd coincidence, this—and while I was pondering it, it flashed into my mind that by helping her I might assist myself. Had aught been needed o strengthen my purpose to serve her, I had it now.

“Yet,” said I, surprise investing my voice,” at Pesaro there is Madonna Lucrezia of that same House of Borgia.”

She smiled away the doubt my words implied.

“Madonna Lucrezia is my friend,” said she; “as sweet and gentle a friend as ever woman had, and she will stand by me even against her own family.”

Since she was satisfied of that, I waived the point, and returned to what was of more immediate interest.

“And you fled,” said I, “with these?” And I indicated her attendants. “Not content to leave the clearest of tracks behind you in the snow, you have had yourself attended by four grooms in the livery of Santafior. So that by asking a few questions any that were so inclined might follow you with ease.”

She opened wide her eyes at that. Oftentimes have I observed that it needs a fool to teach some elementary wisdom to the wise ones of this world. I leapt from my saddle and stood in the road beside her, the bridle on my arm.

“Listen now, Madonna. If you would make good your escape it first imports that you should rid yourself of this valiant escort. Separate from it for a little while. Take you my horse—it is a very gentle beast, and it wilt carry you with safety—and ride on, alone, to Cagli.”

“Alone?” quoth she, in some surprise.

“Why, yes,” I answered gruffly. “What of that? At the Inn of ‘The Full Moon’ ask for the hostess, and tell her that you are to await an escort there, begging her, meanwhile, to place you under her protection. She is a worthy

Comments (0)