The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

[3] Pay a trademark license fee to the Project of 20% of the gross profits you derive calculated using the method you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. If you don’t derive profits, no royalty is due. Royalties are payable to “Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation” the 60 days following each date you prepare (or were legally required to prepare) your annual (or equivalent periodic) tax return. Please contact us beforehand to let us know your plans and to work out the details.

WHAT IF YOU WANT TO SEND MONEY EVEN IF YOU DON’T HAVE TO? The Project gratefully accepts contributions of money, time, public domain etexts, and royalty free copyright licenses. If you are interested in contributing scanning equipment or software or other items, please contact Michael Hart at: hart@pobox.com

END THE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN ETEXTSVer.04.07.00*END*

This etext was produced by John Stuart Middleton <johnmiddleton@netzero.net>

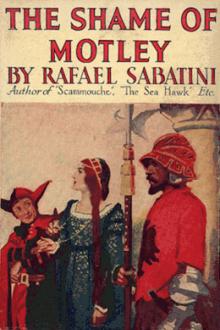

The Shame of Motley Being the Memoir of Certain Transactions in the Life of Lazzaro Biancomonte, of Biancomonte, sometime Fool of the Court of Pesaro.

by Rafael Sabatini

CONTENTS

II. THE LIVERIES OF SANTAFIOR

III. MADONNA PAOLA

IV. THE COZENING OF RAMIRO

V. MADONNA’S INGRATITUDE

VI. FOOL’S LUCK

VII. THE SUMMONS FROM ROME

VIII. “MENE, MENE, TEKEL, UPHARSIN”

IX. THE FOOL-AT-ARMS

X. THE FALL OF PESARO

XI. MADONNA’S SUMMONS

XII. THE GOVERNOR OF CESENA

XIII. POISON

XIV. REQUIESCAT!

XV. AN ILL ENCOUNTER

XVI. IN THE CITADEL OF CESENA

XVII. THE SENESCHAL

XVIII. THE LETTER

XIX. DOOMED

XX. THE SUNSET

XXI. AVE CAESAR!

For three days I had been cooling my heels about the Vatican, vexed by suspense. It fretted me that I should have been so lightly dealt with after I had discharged the mission that had brought me all the way from Pesaro, and I wondered how long it might be ere his Most Illustrious Excellency the Cardinal of Valencia might see fit to offer me the honourable employment with which Madonna Lucrezia had promised me that he would reward the service I had rendered the House of Borgia by my journey.

Three days were sped, yet nought had happened to signify that things would shape the course by me so ardently desired; that the means would be afforded me of mending my miserable ways, and repairing the wreck my life had suffered on the shoals of Fate. True, I had been housed and fed, and the comforts of indolence had been mine; but, for the rest, I was still clothed in the livery of folly which I had worn on my arrival, and, wherever I might roam, there followed ever at my heels a crowd of underlings, seeking to have their tedium lightened by jests and capers, and voting me—when their hopes proved barren—the sorriest Fool that had ever worn the motley.

On that third day I speak of, my patience tried to its last strand, I had beaten a lacquey with my hands, and fled from the cursed gibes his fellows aimed at me, out into the misty gardens and the chill January air, whose sting I could, perhaps, the better disregard by virtue of the heat of indignation that consumed me. Was it ever to be so with me? Could nothing lift the curse of folly from me, that I must ever be a Fool, and worse, the sport of other fools?

It was there on one of the terraces crowning the splendid heights above immortal Rome that Messer Gianluca found me. He greeted me courteously; I answered with a snarl, deeming him come to pursue the plaguing from which I had fled.

“His Most Illustrious Excellency the Cardinal of Valencia is asking for you, Messer Boccadoro,” he announced. And so despairing had been my mood of ever hearing such a summons that, for a moment, I accounted it some fresh jest of theirs. But the gravity of his fat countenance reassured me.

“Let us go, then,” I answered with alacrity, and so confident was I that the interview to which be bade me was the first step along the road to better fortune, that I permitted myself a momentary return to the Fool’s estate from which I thought myself on the point of being for ever freed.

“I shall use the interview to induce his Excellency to submit a tenth beatitude to the approval of our Holy Father: Blessed are the bearers of good tidings. Come on, Messer the seneschal.”

I led the way, in my impatience forgetful of his great paunch and little legs, so that he was sorely tried to keep pace with me. Yet who would not have been in haste, urged by such a spur as had I? Here, then, was the end of my shameful travesty. To-morrow a soldier’s harness should replace the motley of a jester; the name by which I should be known again to men would be that of Lazzaro Biancomonte, and no longer Boccadoro—the Fool of the golden mouth.

Thus much had Madonna Lucrezia’s promises led me to expect, and it was with a soul full of joyous expectation that I entered the great man’s closet.

He received me in a manner calculated to set me at my ease, and yet there was about him a something that overawed me. Cesare Borgia, Cardinal of Valencia, was then in his twenty-third year, for all that there hung about him the semblance of a greater age, just as his cardinalitial robes lent him the appearance of a height far above the middle stature that was his own. His face was pale and framed in a silky auburn beard; his nose was aquiline and strong; his eyes the keenest that I have ever seen; his forehead lofty and intelligent. He seemed pervaded by an air of feverish restlessness, something surpassing the vivida vis animi, something that marked him to discerning eyes for a man of incessant action of body and of mind.

“My sister tells me,” he said in greeting, “that you are willing to take service under me, Messer Biancomonte.”

“Such was the hope that guided me to Rome, Most Excellent,” I answered him.

Surprise flashed into his eyes, and was gone as quickly as it had come. His thin lips parted in a smile, whose meaning was inscrutable.

“As some reward for the safe delivery of the letter you brought me from her?” he questioned mildly.

“Precisely, Illustrious,” I answered in all frankness.

His open hand smote the table of wood-mosaics at which be sat.

“Praised be Heaven!” he cried. “You seem to promise that I shall have in you a follower who deals in truth.”

“Could your Excellency, to whom my real name is known, expect ought else of one who bears it—however unworthily?”

There was amusement in his glance.

“Can you still swagger it, after having worn that livery for three years?” he asked, and his lean forefinger pointed at my hideous motley of red and black and yellow.

I flushed and hung my head, and—as if to mock that very expression of my shame—the bells on my cap gave forth a silvery tinkle at the movement.

“Excellency, spare me,” I murmured. “Did you know all my miserable story you would be merciful. Did you know with what joy I turned my back on the Court of Pesaro—”

“Aye,” he broke in mockingly, “when Giovanni Sforza threatened to have you hanged for the overboldness of your tongue. Not until then did it occur to you to turn from the shameful life in which the best years of your manhood were being wasted. There! Just now I commended your truthfulness; but the truth that dwells in you is no more, it seems, than the truth we may look for in the mouth of Folly. At heart, I fear, you are a hypocrite, Messer Biancomonte; the worst form of hypocrite—a hypocrite to your own self.”

“Did your Excellency know all!” I cried.

“I know enough,” he answered, with stern sorrow; “enough to make me marvel that the son of Ettore Biancomonte of Biancomonte should play the Fool to Costanzo Sforza, Lord of Pesaro. Oh you will tell me that you went there for revenge, to seek to right the wrong his father did your father.”

“It was, it was!” I cried, with heated vehemence. Be flames everlasting the dwelling of my soul if any other motive drove me to this shameful trade.”

There was a pause. His beautiful eyes flamed with a sudden light as they rested on me. Then the lids drooped demurely, and he drew a deep breath. But when he spoke there was scorn in his voice.

“And, no doubt, it was that same motive kept you there, at peace for three whole years, in slothful ease, the motleyed Fool, jesting and capering for his enemy’s delectation—you, a man with the knightly memory of your foully-wronged parent to cry hourly shame upon you. No doubt you lacked the opportunity to bring the tyrant to account. Or was it that you were content to let him make a mock of you so long as he housed and fed you and clothed you in your garish livery of shame?

“Spare me, Excellency,” I cried again. “Of your charity let my past be done with. When he drove me forth with threats of hanging, from which your gracious sister saved me, I turned my steps to Rome at her bidding to—”

“To find honourable employment at my hands,” he interrupted quietly. Then suddenly rising, and speaking in a voice of thunder—” And what, then, of your revenge?” he cried.

“It has been frustrated,” I answered lamely. “Sufficient do I account the ruin that already I have wrought in my life by the pursuit of that phantom. I was trained to arms, my lord. Let me discard for good these tawdry rags, and strap a soldier’s harness to my back.”

“How came you to journey hither thus?” he asked, suddenly turning the subject.

“It was Madonna Lucrezia’s wish. She held that my errand would be safer so, for a Fool may travel unmolested.”

He nodded that he understood, and paced the chamber with bowed head. For a spell there was silence, broken only by the soft fall of his slippered feet and the swish of his silken purple. At last he paused before me and looked up into my face—for I was a good head taller than he was. His fingers combed his auburn beard, and his beautiful eyes were full on mine.

“That was a wise precaution of my sister’s,” he approved. “I will take a lesson from her in the matter. I have employment for you, Messer Biancomonte.”

I bowed my head in token of my gratitude.

“You shall find me diligent and faithful, my lord,” I promised him.

“I know it,” he sniffed, “else should I not employ you.”

He turned from me, and stepped back to his table. He took up a package, fingered it a moment, then dropped it again, and shot me one of his quiet glances.

“That is my answer to Madonna Lucrezia’s letter,” he said slowly, his voice as smooth as silk, “and I desire that you shall carry it to Pesaro for me, and deliver it safely and secretly into her hands.”

I could do no more than stare at him. It seemed as if my mind were stricken numb.

“Well?” he asked at last; and in his voice there was now a suggestion of steel beneath the silk. “Do you hesitate?”

“And if I do,” I answered, suddenly finding my voice, “I do no more than

Comments (0)