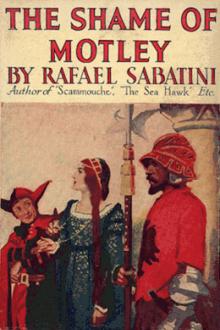

The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

“And then?” she inquired eagerly.

“Then, wait you there until to-night, or even until to-morrow morning, for these knaves to rejoin you to the end that you may resume your journey.”

“But we—” began Giacopo. Scenting his protest, I cut him short.

“You four,” said I, “shall escort me—for I shall replace Madonna in the litter—you shall escort me towards Fabriano. Thus shall we draw the pursuit upon ourselves, and assure your lady a clear road of escape.”

They swore most roundly and with great circumstance of oaths that they would lend themselves to no such madness, and it took me some moments to persuade them that I was possessed of a talisman that should keep us all from harm.

“Were it otherwise, dolts, do you think I should be eager to go with you? Would any chance wayfarer so wantonly imperil his neck for the sake of a lady with whom he can scarce be called acquainted?”

It was an argument that had weight with them, as indeed, it must have had with the dullest. I flashed my ring before their eyes.

“This escutcheon,” said I, “is the shield that shall stand between us and danger from any of the house that bears these arms.”

Thus I convinced and wrought upon them until they were ready to obey me— the more ready since any alternative was really to be preferred to their present situation. In danger they already stood from those that followed as they well knew; and now it seemed to them that by obeying one who was armed with such credentials, it might be theirs to escape that danger. But even as I was convincing them, by the same arguments was I sowing doubts in the lady’s subtler mind.

“You are attached to that house?” quoth she, in accents of mistrust. She wanted to say more. I saw it in her eyes that she was wondering was there treachery underlying an action so singularly disinterested as to justify suspicion.

“Madonna,” said I, “if you would save yourself I implore that you will trust me. Very soon your pursuers will be appearing on those heights, and then your chance of flight will be lost to you. I will ask you but this: Did I propose to betray you into their hands, could I have done better than to have left you with your grooms?”

Her face lighted. A sunny smile broke on me from her heavenly eyes.

“I should have thought of that,” said she. And what more she would have added I put off by urging her to mount.

Sitting the man’s saddle as best she might—well enough, indeed, to fill us all with surprise and admiration—she took her leave of me with pretty words of thanks, which again I interrupted.

“You have but to follow the road,” said I, “and it will bring you straight to Cagli. The distance is a short league, and you should come there safely. Farewell, Madonna!”

“May I not know,” she asked at parting, “the name of him that has so generously befriended me?”

I hesitated a second. Then—“They call me Boccadoro,” answered I.

“If your mouth be as truly golden as your heart, then are you well-named,” said she. Then, gathering her mantle about her, and waving me farewell, she rode off without so much as a glance at the cowardly hinds who had failed her in the hour of her need.

A moment I stood watching her as she cantered away in the sunshine; then stepping to the litter, I vaulted in.

“Now, rogues,” said I to the escort, “strike me that road to Fabriano.”

“I know you not, sir,” protested Giacopo. “But this I know—that if you intend us treachery you shall have my knife in your gullet for your pains.”

“Fool!” I scorned him,” since when has it been worth the while of any man to betray such creatures as are you? Plague me no more! Be moving, else I leave you to your coward’s fate.”

It was the tone best understood by hinds of their lily�livered quality. It quelled their faint spark of mutiny, and a moment later one of those knaves had caught the bridle of the leading mule and the litter moved forward, whilst Giacopo and the others came on behind at as brisk a pace as their weary horses would yield. In this guise we took the road south, in the direction opposite to that travelled by the lady. As we rode, I summoned Giacopo to my side.

“Take your daggers,” I bade him, “and rip me that blazon from your coats. See that you leave no sign about you to proclaim you of the House of Santafior, or all is lost. It is a precaution you would have taken earlier if God had given you the wit of a grasshopper.”

He nodded that he understood my order, and scowled his disapproval of my comment on his wit. For the rest, they did my bidding there and then.

Having satisfied myself that no betraying sign remained about them, I drew the curtains of my litter, and reclining there I gave myself up to pondering the manner in which I should greet the Borgia sbirri when they overtook me. From that I passed on to the contemplation of the position in which I found myself, and the thing that I had done. And the proportions of the jest that I was perpetrating afforded me no little amusement. It was a burla not unworthy the peerless gifts of Boccadoro, and a fitting one on which to close his wild career of folly. For had I not vowed that Boccadoro I would be no more once the errand on which I travelled was accomplished? By Cesare Borgia’s grace I looked to—

A sudden jolt brought me back to the immediate present, and the realisation that in the last few moments we had increased our pace. I put out my head.

“Giacopo!” I shouted. He was at my side in an instant. “Why are we galloping?”

“They are behind,” he answered, and fear was again overspreading his fat face. “We caught a glimpse of them as we mounted the last hill.”

“You caught a glimpse of whom?” quoth I.

“Why, of the Borgia soldiers.”

“Animal,” I answered him, “what have we to do with them? They may have mistaken us for some party of which they are in pursuit. But since we are not that party, let your jaded beasts travel at a more reasonable speed. We do not wish to have the air of fugitives.”

He understood me, and I was obeyed. For a half-hour we rode at a more gentle pace. That was about the time they took to come up with us, still a league or so from Fabriano. We heard their cantering hoofs crushing the snow, and then a loud imperious voice shouting to us a command to stay. Instantly we brought up in unconcerned obedience, and they thundered alongside with cries of triumph at having run their prey to earth.

I cast aside my hat, and thrust my motleyed head through the curtains with a jangle of bells, to inquire into the reason of this halt. Whom my appearance astounded the more—whether the lacqueys of Santafior, or the Borgia men-at-arms that now encircled us—I cannot guess. But in the crowd of faces that confronted me there was not one but wore a look of deep amazement.

The cavalcade that had overtaken us proved to number some twenty men-at- arms, whose leader was no less a person than Ramiro del’ Orca—that same mountain of a man who had attended my departure from the Vatican three nights ago. From the circumstance that so important a personage should have been charged with the pursuit of the Lady of Santafior, I inferred that great issues were at stake.

He was clad in mail and leather, and from his lance fluttered the bannerol bearing the Borgia arms, which had announced his quality to Madonna’s servants.

At sight of me his bloodshot eyes grew round with wonder, and for a little season a deathly calm preceded the thunder of his voice.

“Sainted Host!” he roared at last. “What trickery may this be?” And sidling his horse nearer he tore aside the curtains of my litter.

Out of faces pale as death the craven grooms looked on, to behold me reclining there, my cloak flung down across my legs to hide my boots, and my motley garb of red and black and yellow all revealed. I believe their astonishment by far surpassed the Captain’s own.

“You are choicely met, Ser Ramiro,” I greeted him. Then, seeing that he only stared, and made no shift to speak: “Maybe,” quoth I, “you’ll explain why you detain me. I am in haste.”

“Explain?” he thundered. “Sangue di Cristo! The burden of explaining lies with you. What make you here?”

“Why,” answered I, in tones of deep astonishment, “I am about the business of the Lord Cardinal of Valencia, our master.”

“Davvero?” he jeered. He stretched out a mighty paw, and took me by the collar of my doublet. “Now, bethink you how you answer me, or there will be a fool the less in the world.”

“Indeed, the world might spare more.”

He scowled at my pleasantry. To him, apparently, the situation afforded no scope for philosophical reflections.

“Where is the girl?” he asked abruptly.

“Girl?” quoth I. “What girl? Am I a mother�abbess, that you should set me such a question?”

Two dark lines showed between his brows. His voice quivered with passion.

“I ask you again—where is the girl?”

I laughed like one who is a little wearied by the entertainment provided for him.

“Here be no girls, Messer del’ Orca,” I answered him in the same tone. “Nor can I think what this babble of girls portends.”

My seeming innocence, and the assurance with which I maintained the expression of it, whispered a doubt into his mind. He released me, and turned upon his men, a baffled look in his eyes.

“Was not this the party?” he inquired ferociously. “Have you misled me, beasts?

“It seemed the party, Illustrious,” answered one of them.

“Do you dare tell me that ‘it seemed’?” he roared, seeking to father upon them the blunder he was beginning to fear that he had made. “But—What is the livery of these knaves?

“They wear none,” someone answered him, and at that answer he seemed to turn limp and lose his fierce assurance.

Then he bridled afresh.

“Yet the party, I’ll swear, is this!” he insisted; and turning once more to me: “Explain, animal!” be bade me in terrifying tones. “Explain, or, by the Host! be you ignorant or not, I’ll have you hanged.”

I accounted it high time to take another tone with him. Hanging was a discomfort I was never less minded to suffer.

“Draw nearer, fool,” said I contemptuously, and at the epithet, so greatly did my audacity amaze him, he mildly did my bidding.

“I know not what doubts are battling in your thick head, sir captain,” I pursued. “But this I know—that if you persist in hindering me, or commit the egregious folly of offering me violence, you will answer for it, hereafter, to the Lord Cardinal of Valencia.

“I am going upon a secret mission”—and here I sank my voice to a whisper for his ears alone—“in the service of the house that hires you, as for yourself you might easily have inferred. Behold.” And I revealed my ring. “Detain me longer at your peril.”

He must have had some notion of the fact that I was journeying in Cesare Borgia’s service, and this coupled with the sight of that talisman effected in his manner

Comments (0)