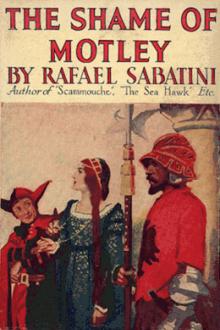

The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley, Rafael Sabatini [english novels to improve english .TXT] 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

The lady’s face grew clouded as she listened, for from my insistence she shrewdly inferred that it imported to be gone.

“There is your ostler,” quoth I at last. “He will do for one.”

“He is the only man I have. My husband and my sons are gone to Pesaro.”

“Yet spare us this one, and you shall be well paid his services.”

But no bribe could tempt her to give way, and no doubt she was well-advised, for she contended that there was work to be done such as was beyond her years and strength, and that if she sent her ostler off, as well might she close her inn—a thing that was impossible.

Here, then, was an obstacle with which I had not reckoned. It was impossible to send the lady off alone, to travel a distance of some ten leagues, and the most of it by night—for if she would make sure of escaping, she must journey now without pause until she came to Pesaro.

And then, in a flash, it occurred to me that here lay the means, ready to my hand, by avail of which I might boldly re-enter Pesaro despite my banishment, and discharge my errand to Lucrezia Borgia. For, surely, considering the mission on which ostensibly I should be returning—as the saviour and protector of his kinswoman—Giovanni Sforza could not enforce that ban against me. Next I bethought me of the other aspect that the business wore. In fooling Ramiro I had thwarted the Borgia ends; in rescuing Madonna Paola I had perhaps set at naught the Cardinal of Valencia’s aims. If so, what then? It would seem that because the lady’s eyes were mild and sweet, and because her beauty had so deeply wrought upon me, I had indeed fooled away my chance of salvation from the life and trade that were grown hateful to me. For back to Rome and Cesare Borgia I should dare go no more. Clearly I had burned my boats, and I had done it almost unthinkingly, acting upon the good impulse to befriend this lady, and never reckoning the cost down to its total. For all that the thing I had done, and what I might yet do, should offer me the means I needed to enter Pesaro without danger to my neck, I did not see that I was to derive great profit in the end—unless my profit lay in knowing that I had advanced the ruin of Giovanni Sforza by delivering my letter to Lucrezia. That at any rate was enough incentive clearly to define for me the line that I should take through this tangle into which the ever-jesting Fates had thrust me.

I was still at my thoughts, still pondering this most perplexing situation, the hostess standing silent by the door, when suddenly Madonna Paola spoke.

“Sir,” said she, in faltering accents, “I—I have not the right to ask you, and I stand already so deeply in your debt. Not a doubt of it, but it will have inconvenienced you to have journeyed thus far to inform me of the flight of my grooms. Yet if you could—” She paused, timid of proceeding, and her glance fell.

The hostess was all ears, struck by the respectful manner in which this very evidently noble lady addressed a Fool. I opened the door for her.

“You may leave us now,” said I. “I will come to you presently.”

When she was gone I turned once more to the lady, my course resolved upon. My hate had conquered my last doubt. What first imported was that I should get to Pesaro and to Madonna Lucrezia.

“You were about to ask me,” said I, “that I should accompany you to Pesaro.”

“I hesitated, sir,” she murmured. I bowed respectfully.

“There was not the need, Madonna,” I assured her. “I am at your service.”

“But, Messer Boccadoro, I have no claim upon you.”

“Surely,” said I, “the claim that every distressed lady has upon a man of heart. Let us say no more. It were best not to delay in setting out, although I can scarcely think that there is any imminent danger from Ramiro del’ Orca now.”

“Who is he?” she inquired. I told her, whereupon—”

Did they come up with you?” she asked. “What passed between you?”

Succinctly I related what had chanced, and how I had sent Ramiro on a fool’s errand, adding the particulars of the flight of her grooms, and of how I had rid myself of the litter and the second mule. She heard me, her eyes sparkling, and at times she clapped her hands with a glee that was almost childish, vowing that this was splendid, that was brave. I allayed what little fears remained her by pointing out how effectively we had effaced our tracks, and how vainly now Messer del’ Orca might beat the country in quest of a lady in a litter, escorted by four grooms.

And now she beset me with fresh thanks and fresh expressions of wonder at my generous readiness to befriend her—a wonder all devoid of suspicion touching the single-mindedness of my purpose. But I reminded her that we had little leisure to stand talking, and left her to make her preparations for the journey, whilst I went below to see that my mule and her horse were saddled. I made bold to pay the reckoning, and when presently she spoke of it, with flaming cheeks, and would have pledged me a jewel, I bade her look upon it as a loan which anon she might repay me when I had brought her safely to her kinsman’s Court at Pesaro.

Thus, at last, we left Cagli, and took the road north, riding side by side and talking pleasantly the while, ever concerning the matter of her flight and of her hopes of shelter at Pesaro, which, being nearest to her heart, found readiest expression. I went wrapped in my cloak once more, my head-dress hidden ‘neath my broad-brimmed hat, so that the few wayfarers we chanced on need not marvel to see a lady in such friendly intercourse with a Fool. And so dull was I that day as not to marvel, myself, at such a state of things.

The sun was declining, a red ball of fire, towards the mountains on our left, casting a blood-red glow upon the snow that everywhere encompassed us, as we cantered briskly on towards Fossombrone.

In that hour I fell to pondering, and I even caught myself hoping that Messer Ramiro del’ Orca might not chance upon the discovery of how egregiously I had fooled him. He was dull-witted and slow at inference, and upon that I built the hope that he might fail to associate me with Madonna Paola’s elusion of his pursuit. Thus the chance might yet be mine of returning to Rome and the honourable employment Cesare Borgia had promised me. If only that were so to fall out, I might yet contrive to mend the wreckage of my life. I was returned, it seems, to the ways of early youth, when we build our hopes of future greatness upon untenable foundations!

Great hopes and great ambitions rose within my breast that January evening, fired by the gentle child that rode beside me. Fate had sent me to her aid that day, and I seemed to have acquired, by virtue of that circumstance, a certain right in her. Had Fate no other favours for me in her lap! I bethought me of the very House of Sforza, to which I had been so shamefully attached, and of its humble source in that peasant, Giacomuzzo Attendolo, surnamed Sforza for his abnormal strength of body, who rose to great and princely heights.

Assuredly I had the advantage of such an one, and were the chance but given me—

I went no further. Down in my heart I laughed to scorn my own wild musings. Cesare Borgia would come to know—he must, whether Ramiro told him, or whether he inferred it for himself from the account Ramiro must give him of our meeting—how I had thwarted him in one thing, whilst I had served him in another. Fate was against me. I had fallen too low to ever rise again, and no dreams indulged in a sunset hour, and inspired, perhaps, by a child who was beautiful as one of the saints of God, would ever come to be realised by poor Boccadoro.

Night was falling as we clattered through the slippery streets of Fossombrone.

We stayed in Fossombrone little more than a half-hour, and having made a hasty supper we resumed our way, giving out that we wished to reach Fano ere we slept. And so by the first hour of night Fossombrone was a league or so behind us, and we were advancing briskly towards the sea. Overhead a moon rode at the full in a clear sky, and its light was reflected by the snow, so that we were not discomforted by any darkness. We fell, presently, into a gentler pace, for, after all, there could be no advantage in reaching Pesaro before morning, and as we rode we talked, and I made bold to ask her the cause of her flight from Rome.

She told me then that she was Madonna Paola Sforza di Santafior, and that Pope Alexander, in his nepotism and his desire to make rich and powerful alliances for his family, had settled upon her as the wife for his nephew, Ignacio Borgia. He had been emboldened to this step by the fact that her only protector was her brother, Filippo di Santafior, whom they had sought to coerce. It was her brother, who, seeing himself in a dangerous and unenviable position, had secretly suggested flight to her, urging her to repair to her kinsman Giovanni Sforza at Pesaro. Her flight, however, must have been speedily discovered and the Borgias, who saw in that act a defiance of their supreme authority, had ordered her pursuit.

But for me, she concluded, that pursuits must have resulted in her capture, and once they had her back in Rome, willing or unwilling, they would have driven her into the alliance by means of which they sought to bring her fortune into their own house. This drew her into fresh protestations of the undying gratitude she entertained towards me, protestations which I would have stemmed, but that she persisted in them.

“It is a good and noble thing that you have done,” said she, “and I think that Heaven must have directed you to my aid, for it is scarce likely that in all Italy I should have found another man who would have done so much.”

“Why, what, after all, is this much that I have done?” I cried. “It is no less than my manhood bade me do; no less than any other would have done seeing you so beset.”

“Nay, that is more than I can ever think,” she answered. “Who for the sake of an unknown would have suffered such inconveniences as have you? Who would have returned as you have returned to advise me of the defection of my grooms? Who, when other escort failed, would have gone the length of journeying all this way to render a service that is beyond repayment? And, above all, who for the sake of an unknown maid would have submitted to this travesty of yours?”

“Travesty?” quoth I, so struck by that as to interrupt her at last. “What travesty, Madonna?”

“Why, this garb of motley that you donned the better to fool my pursuers and that you still wear in my poor service.”

I turned in the saddle to stare at her, and in the moonlight I clearly saw her eyes

Comments (0)