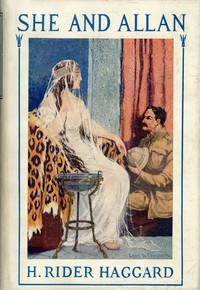

She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗

- Author: H. Rider Haggard

Book online «She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗». Author H. Rider Haggard

This was true, for I found that, strive as I would, I could not move a limb or even an eyelid. I was frozen to that spot and there was nothing for it except to curse my folly and say my prayers.

All this while she went on talking, but of what she said I have not the faintest idea, because my remaining wits were absorbed in these much-needed implorations.

Presently, of a sudden, I appeared to see Ayesha seated in a temple, for there were columns about her, and behind her was an altar on which a fire burned. All round her, too, were hooded snakes like to that which she wore about her middle, fashioned in gold. To these snakes she sang and they danced to her singing; yes, with flickering tongues they danced upon their tails! What the scene signified I cannot conceive, unless it meant that this mistress of magic was consulting her familiars.

Then that vision vanished and Ayesha’s voice began to seem very far away and dreamy, also her wondrous beauty became visible to me through her veil, as though I had acquired a new sense that overcame the limitations of mortal sight. Even in this extremity I reflected it was well that the last thing I looked on should be something so glorious. No, not quite the last thing, for out of the corners of my eyes I saw that Umslopogaas from a sitting position had sunk on to his back and lay, apparently dead, with his axe still gripped tightly and held above his head, as though his arm had been turned to ice.

After this terrible things began to happen to me and I became aware that I was dying. A great wind seemed to catch me up and blow me to and fro, as a leaf is blown in the eddies of a winter gale. Enormous rushes of darkness flowed over me, to be succeeded by vivid bursts of brightness that dazzled like lightning. I fell off precipices and at the foot of them was caught by some fearful strength and tossed to the very skies.

From those skies I was hurled down again into a kind of whirlpool of inky night, round which I spun perpetually, as it seemed for hours and hours. But worst of all was the awful loneliness from which I suffered. It seemed to me as though there were no other living thing in all the Universe and never had been and never would be any other living thing. I felt as though I were the Universe rushing solitary through space for ages upon ages in a frantic search for fellowship, and finding none.

Then something seemed to grip my throat and I knew that I had died—for the world floated away from beneath me.

Now fear and every mortal sensation left me, to be replaced by a new and spiritual terror. I, or rather my disembodied consciousness, seemed to come up for judgment, and the horror of it was that I appeared to be my own judge. There, a very embodiment of cold justice, my Spirit, grown luminous, sat upon a throne and to it, with dread and merciless particularity I set out all my misdeeds. It was as if some part of me remained mortal, for I could see my two eyes, my mouth and my hands, but nothing else—and strange enough they looked. From the eyes came tears, from the mouth flowed words and the hands were joined, as though in prayer to that throned and adamantine Spirit which was ME.

It was as though this Spirit were asking how my body had served its purposes and advanced its mighty ends, and in reply—oh! what a miserable tale I had to tell. Fault upon fault, weakness upon weakness, sin upon sin; never before did I understand how black was my record. I tried to relieve the picture with some incidents of attempted good, but that Spirit would not hearken. It seemed to say that it had gathered up the good and knew it all. It was of the evil that it would learn, not of the good that had bettered it, but of the evil by which it had been harmed.

Hearing this there rose up in my consciousness some memory of what Ayesha had said; namely, that the body lived within the temple of the spirit which is oft defied, and not the spirit in the body.

The story was told and I hearkened for the judgment, my own judgment on myself, which I knew would be accepted without question and registered for good or ill. But none came, since ere the balance sank this way or that, ere it could be uttered, I was swept afar.

Through Infinity I was swept, and as I fled faster than the light, the meaning of what I had seen came home to me. I knew, or seemed to know for the first time, that at the last man must answer to himself, or perhaps to a divine principle within himself, that out of his own free-will, through long æons and by a million steps, he climbs or sinks to the heights or depths dormant in his nature; that from what he was, springs what he is, and what he is, engenders what he shall be for ever and aye.

Now I envisaged Immortality and splendid and awful was its face. It clasped me to its breast and in the vast circle of its arms I was up-borne, I who knew myself to be without beginning and without end, and yet of the past and of the future knew nothing, save that these were full of mysteries.

As I went I encountered others, or overtook them, making the same journey. Robertson swept past me, and spoke, but in a tongue I could not understand. I noted that the madness had left his eyes and that his fine-cut features were calm and spiritual. The other wanderers I did not know.

I came to a region of blinding light; the thought rose in me that I must have reached the sun, or a sun, though I felt no heat. I stood in a lovely, shining valley about which burned mountains of fire. There were huge trees in that valley, but they glowed like gold and their flowers and fruit were as though they had been fashioned of many-coloured flames.

The place was glorious beyond compare, but very strange to me and not to be described. I sat me down upon a boulder which burned like a ruby, whether with heat or colour I do not know, by the edge of a stream that flowed with what looked like fire and made a lovely music. I stooped down and drank of this water of flames and the scent and the taste of it were as those of the costliest wine.

There, beneath the spreading limbs of a fire-tree I sat, and examined the strange flowers that grew around, coloured like rich jewels and perfumed above imagining. There were birds also which might have been feathered with sapphires, rubies and amethysts, and their song was so sweet that I could have wept to hear it. The scene was wonderful and filled me with exaltation, for I thought of the land where it is promised that there shall be no more night.

People began to appear; men, women, and even children, though whence they came I could not see. They did not fly and they did not walk; they seemed to drift towards me, as unguided boats drift upon the tide. One and all they were very beautiful, but their beauty was not human although their shapes and faces resembled those of men and women made glorious. None were old, and except the children, none seemed very young; it was as though they had grown backwards or forwards to middle life and rested there at their very best.

Now came the marvel; all these uncounted people were known to me, though so far as my knowledge went I had never set eyes on most of them before. Yet I was aware that in some forgotten life or epoch I had been intimate with every one of them; also that it was the fact of my presence and the call of my sub-conscious mind which drew them to this spot. Yet that presence and that call were not visible or audible to them, who, I suppose, flowed down some stream of sympathy, why or whither they did not know. Had I been as they were perchance they would have seen me, as it was they saw nothing and I could not speak and tell them of my presence.

Some of this multitude, however, I knew well enough even when they had departed years and years ago. But about these I noted this, that every one of them was a man or a woman or a child for whom I had felt love or sympathy or friendship. Not one was a person whom I had disliked or whom I had no wish to see again. If they spoke at all I could not hear—or read—their speech, yet to a certain extent I could hear their thoughts.

Many of these were beyond the power of my appreciation on subjects of which I had no knowledge, or that were too high for me, but some were of quite simple things such as concern us upon the earth, such as of friendship, or learning, or journeys made or to be made, or art, or literature, or the wonders of Nature, or of the fruits of the earth, as they knew them in this region.

This I noted too, that each separate thought seemed to be hallowed and enclosed in an atmosphere of prayer or heavenly aspiration, as a seed is enclosed in the heart of a flower, or a fruit in its odorous rind, and that this prayer or aspiration presently appeared to bear the thought away, whither I knew not. Moreover, all these thoughts, even of the humblest things, were beauteous and spiritual, nothing cruel or impure or even coarse was to be found among them: they radiated charity, purity and goodness.

Among them I perceived were none that had to do with our earth; this and its affairs seemed to be left far behind these thinkers, a truth that chilled my soul was alien to their company. Worse still, so far as I could discover, although I knew that all these bright ones had been near to me at some hour in the measurements of time and space, not one of their musings dwelt upon me or on aught with which I had to do.

Between me and them there was a great gulf fixed and a high wall built.

Oh, look! One came shining like a star, and from far away came another with dove-like eyes and beautiful exceedingly, and with this last a maiden, whose eyes were as hers who my own heart told me was her mother.

Well, I knew them both; they were those whom I had come to seek, the women who had been mine upon the earth, and at the sight of them my spirit thrilled. Surely they would discover me. Surely at least they would speak of me and feel my presence.

But, although they stayed within a pace or two of where I rested, alas! it was not so. They seemed to kiss and to exchange swift thoughts about many things, high things of which I will not write, and common things; yes, even of the shining robes they wore, but never a one of me! I strove to rise and go to them, but could not; I strove to speak and could not; I strove to throw out my thought to them and could not; it fell back upon my head like a stone hurled heavenward.

They were remote from me, utterly apart. I wept tears of bitterness that I should be so near and yet so far; a dull and jealous rage burned in my heart, and this they did seem to feel, or so I fancied; at any rate, apparently by mutual consent, they moved further from me as though something pained them. Yes, my love could not reach their perfected natures, but my anger hurt them.

As I sat chewing this root of bitterness, a man appeared, a very noble man, in whom I recognised my father grown younger and happier-looking, but still my father, with whom came others, men and women whom I knew

Comments (0)