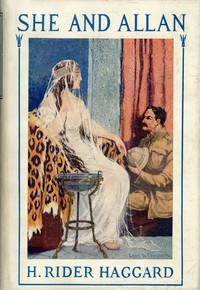

She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗

- Author: H. Rider Haggard

Book online «She and Allan, H. Rider Haggard [best summer reads .txt] 📗». Author H. Rider Haggard

But it was not so. They spoke, or interchanged their thoughts, but not one of me. I read something that passed from my father to them. It was a speculation as to what had brought them all together there, and read also the answer hazarded, that perhaps it might be to give welcome to some unknown who was drawing near from below and would feel lonely and unfriended. Thereon my father replied that he did not see or feel this wanderer, and thought that it could not be so, since it was his mission to greet such on their coming.

Then in an instant all were gone and that lovely, glowing plain was empty, save for myself seated on the ruby-like stone, weeping tears of blood and shame and loss within my soul.

So I sat a long while, till presently I was aware of a new presence, a presence dusky and splendid and arrayed in rich barbaric robes. Straight she came towards me, like a thrown spear, and I knew her for a certain royal and savage woman who on earth was named Mameena, or “Wind-that-wailed.” Moreover she divined me, though see me she could not.

“Art there, Watcher-in-the-Night, watching in the light?” she said or thought, I know not which, but the words came to me in the Zulu tongue.

“Aye,” she went on, “I know that thou art there; from ten thousand leagues away I felt thy presence and broke from my own place to welcome thee, though I must pay for it with burning chains and bondage. How did those welcome thee whom thou camest out to seek? Did they clasp thee in their arms and press their kisses on thy brow? Or did they shrink away from thee because the smell of earth was on thy hands and lips?”

I seemed to answer that they did not appear to know that I was there.

“Aye, they did not know because their love is not enough, because they have grown too fine for love. But I, the sinner, I knew well, and here am I ready to suffer all for thee and to give thee place within this stormy heart of mine. Forget them, then, and come to rule with me who still am queen in my own house that thou shalt share. There we will live royally and when our hour comes, at least we shall have had our day.”

Now before I could reply, some power seemed to seize this splendid creature and whirl her thence so that she departed, flashing these words from her mind to mine,

“For a little while farewell, but remember always that Mameena, the Wailing Wind, being still as a sinful woman in a woman’s love and of the earth, earthy, found thee, whom all the rest forgot. O Watcher-in-the-Night, watch in the night for me, for there thou shalt find me, the Child of Storm, again, and yet again.”

She was gone and once more I sat in utter solitude upon that ruby stone, staring at the jewelled flowers and the glorious flaming trees and the lambent waters of the brook. What was the meaning of it all, I wondered, and why was I deserted by everyone save a single savage woman, and why had she a power to find me which was denied to all the rest? Well, she had given me an answer, because she was “as a sinful woman with a woman’s love and of the earth, earthy,” while with the rest it was otherwise. Oh! this was clear, that in the heavens man has no friend among the heavenly, save perhaps the greatest Friend of all Who understands both flesh and spirit.

Thus I mused in this burning world which was still so beautiful, this alien world into which I had thrust myself unwanted and unsought. And while I mused this happened. The fiery waters of the stream were disturbed by something and looking up I saw the cause.

A dog had plunged into them and was swimming towards me. At a glance I knew that dog on which my eyes had not fallen for decades. It was a mongrel, half spaniel and half bull-terrier, which for years had been the dear friend of my youth and died at last on the horns of a wounded wildebeeste that attacked me when I had fallen from my horse upon the veld. Boldly it tackled the maddened buck, thus giving me time to scramble to my rifle and shoot it, but not before the poor hound had yielded its life for mine, since presently it died disembowelled, but licking my hand and forgetful of its agonies. This dog, Smut by name, it was that swam or seemed to swim the brook of fire. It scrambled to the hither shore, it nosed the earth and ran to the ruby stone and stared about it whining and sniffing.

At last it seemed to see or feel me, for it stood upon its hind legs and licked my face, yelping with mad joy, as I could see though I heard nothing. Now I wept in earnest and bent down to hug and kiss the faithful beast, but this I could not do, since like myself it was only shadow.

Then suddenly all dissolved in a cataract of many-coloured flames and I fell down into an infinite gulf of blackness.

Surely Ayesha was talking to me! What did she say? What did she say? I could not catch her words, but I caught her laughter and knew that after her fashion she was making a mock of me. My eyelids were dragged down as though with heavy sleep; it was difficult to lift them. At last they were open and I saw Ayesha seated on her couch before me and—this I noted at once—with her lovely face unveiled. I looked about me, seeking Umslopogaas and Hans. But they were gone as I guessed they must be, since otherwise Ayesha would not have been unveiled. We were quite alone. She was addressing me and in a new fashion, since now she had abandoned the formal “you” and was using the more impressive and intimate “thou,” much as is the manner of the French.

“Thou hast made thy journey, Allan,” she said, “and what thou hast seen there thou shalt tell me presently. Yet from thy mien I gather this—that thou art glad to look upon flesh and blood again and, after the company of spirits, to find that of mortal woman. Come then and sit beside me and tell thy tale.”

“Where are the others?” I asked as I rose slowly to obey, for my head swam and my feet seemed feeble.

“Gone, Allan, who as I think have had enough of ghosts, which is perhaps thy case also. Come, drink this and be a man once more. Drink it to me whose skill and power have brought thee safe from lands that human feet were never meant to tread,” and taking a strange-shaped cup from a stool that stood beside her, she offered it to me.

I drank to the last drop, neither knowing nor caring whether it were wine or poison, since my heart seemed desperate at its failure and my spirit crushed beneath the weight of its great betrayal. I suppose it was the former, for the contents of that cup ran through my veins like fire and gave me back my courage and the joy of life.

I stepped to the dais and sat me down upon the couch, leaning against its rounded end so that I was almost face to face with Ayesha who had turned towards me, and thence could study her unveiled loveliness. For a while she said nothing, only eyed me up and down and smiled and smiled, as though she were waiting for that wine to do its work with me.

“Now that thou art a man again, Allan, tell me what thou didst see when thou wast more—or less—than man.”

So I told her all, for some power within her seemed to draw the truth out of me. Nor did the tale appear to cause her much surprise.

“There is truth in thy dream,” she said when I had finished; “a lesson also.”

“Then it was all a dream?” I interrupted.

“Is not everything a dream, even life itself, Allan? If so, what can this be that thou hast seen, but a dream within a dream, and itself containing other dreams, as in the old days the ball fashioned by the eastern workers of ivory would oft be found to contain another ball, and this yet another and another and another, till at the inmost might be found a bead of gold, or perchance a jewel, which was the prize of him who could draw out ball from ball and leave them all unbroken. That search was difficult and rarely was the jewel come by, if at all, so that some said there was none, save in the maker’s mind. Yes, I have seen a man go crazed with seeking and die with the mystery unsolved. How much harder, then, is it to come at the diamond of Truth which lies at the core of all our nest of dreams and without which to rest upon they could not be fashioned to seem realities?”

“But was it really a dream, and if so, what were the truth and the lesson?” I asked, determined not to allow her to bemuse or escape me with her metaphysical talk and illustrations.

“The first question has been answered, Allan, as well as I can answer, who am not the architect of this great globe of dreams, and as yet cannot clearly see the ineffable gem within, whose prisoned rays illuminate their substance, though so dimly that only those with the insight of a god can catch their glamour in the night of thought, since to most they are dark as glow-flies in the glare of noon.”

“Then what are the truth and the lesson?” I persisted, perceiving that it was hopeless to extract from her an opinion as to the real nature of my experiences and that I must content myself with her deductions from them.

“Thou tellest me, Allan, that in thy dream or vision thou didst seem to appear before thyself seated on a throne and in that self to find thy judge. That is the Truth whereof I spoke, though how it found its way through the black and ignorant shell of one whose wit is so small, is more than I can guess, since I believed that it was revealed to me alone.”

(Now I, Allan, thought to myself that I began to see the origin of all these fantasies and that for once Ayesha had made a slip. If she had a theory and I developed that same theory in a hypnotic condition, it was not difficult to guess its fount. However, I kept my mouth shut, and luckily for once she did not seem to read my mind, perhaps because she was too much occupied in spinning her smooth web of entangling words.)

“All men worship their own god,” she went on, “and yet seem not to know that this god dwells within them and that of him they are a part. There he dwells and there they mould him to their own fashion, as the potter moulds his clay, though whatever the shape he seems to take beneath their fingers, still he remains the god infinite and unalterable. Still he is the Seeker and the Sought, the Prayer and its Fulfilment, the Love and the Hate, the Virtue and the Vice, since all these qualities the alchemy of his spirit turns into an ultimate and eternal Good. For the god is in all things and all things are in the god, whom men clothe with such diverse garments and whose countenance they hide beneath so many masks.

“In the tree flows the sap, yet what knows the great tree it nurtures of the sap? In the world’s womb burns the fire that gives life, yet what of the fire knows the glorious earth it conceived and will destroy; in the heavens the great globes swing through space and rest not, yet what know they of the Strength that sent them spinning and in a time to come will stay their mighty motions, or turn them to another course? Therefore of everything this all-present god is judge, or rather, not one but many judges, since of each living creature he makes its own magistrate to deal out justice according to that creature’s law which

Comments (0)