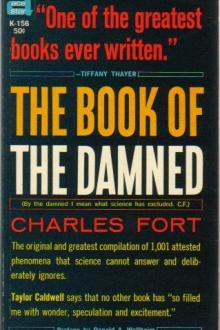

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

It may be that something aimed at that town, and then later took another shot.

These are speculations that seem to me to be evil relatively to these early years in the twentieth century—

Just now, I accept that this earth is—not round, of course: that is very old-fashioned—but roundish, or, at least, that it has what is called form of its own, and does revolve upon its axis, and in an orbit around the sun. I only accept these old traditional notions—

And that above it are regions of suspension that revolve with it: from which objects fall, by disturbances of various kinds, and then, later, fall again, in the same place:

Monthly Weather Review, May, 1884-134:

Report from the Signal Service observer, at Bismarck, Dakota:

That, at 9 o'clock, in the evening of May 22, 1884, sharp sounds were heard throughout the city, caused by a fall of flinty stones striking against windows.

Fifteen hours later another fall of flinty stones occurred at Bismarck.

There is no report of stones having fallen anywhere else.

This is a thing of the ultra-damned. All Editors of scientific publications read the Monthly Weather Review and frequently copy from it. The noise made by the stones of Bismarck, rattling against those windows, may be in a language that aviators will some day interpret: but it was a noise entirely surrounded by silences. Of this ultra-damned thing, there is no mention, findable by me, in any other publication.

The size of some hailstones has worried many meteorologists—but not text-book meteorologists. I know of no more serene occupation than that of writing text-books—though writing for the War Cry, of the Salvation Army, may be equally unadventurous. In the drowsy tranquillity of a text-book, we easily and unintelligently read of dust particles around which icy rain forms, hailstones, in their fall, then increasing by accretion—but in the meteorological journals, we read often of air-spaces nucleating hailstones—

But it's the size of the things. Dip a marble in icy water. Dip and dip and dip it. If you're a resolute dipper, you will, after a while, have an object the size of a baseball—but I think a thing could fall from the moon in that length of time. Also the strata of them. The Maryland hailstones are unusual, but a dozen strata have often been counted. Ferrel gives an instance of thirteen strata. Such considerations led Prof. Schwedoff to argue that some hailstones are not, and cannot, be generated in this earth's atmosphere—that they come from somewhere else. Now, in a relative existence, nothing can of itself be either attractive or repulsive: its effects are functions of its associations or implications. Many of our data have been taken from very conservative scientific sources: it was not until their discordant implications, or irreconcilabilities with the System, were perceived, that excommunication was pronounced against them.

Prof. Schwedoff's paper was read before the British Association (Rept. of 1882, p. 453).

The implication, and the repulsiveness of the implication to the snug and tight little exclusionists of 1882—though we hold out that they were functioning well and ably relatively to 1882—

That there is water—oceans or lakes and ponds, or rivers of it—that there is water away from, and yet not far-remote from, this earth's atmosphere and gravitation—

The pain of it:

That the snug little system of 1882 would be ousted from its reposefulness—

A whole new science to learn:

The Science of Super-Geography—

And Science is a turtle that says that its own shell encloses all things.

So the members of the British Association. To some of them Prof. Schwedoff's ideas were like slaps on the back of an environment-denying turtle: to some of them his heresy was like an offering of meat, raw and dripping, to milk-fed lambs. Some of them bleated like lambs, and some of them turled like turtles. We used to crucify, but now we ridicule: or, in the loss of vigor of all progress, the spike has etherealized into the laugh.

Sir William Thomson ridiculed the heresy, with the phantomosities of his era:

That all bodies, such as hailstones, if away from this earth's atmosphere, would have to move at planetary velocity—which would be positively reasonable if the pronouncements of St. Isaac were anything but articles of faith—that a hailstone falling through this earth's atmosphere, with planetary velocity, would perform 13,000 times as much work as would raise an equal weight of water one degree centigrade, and therefore never fall as a hailstone at all; be more than melted—super-volatalized—

These turls and these bleats of pedantry—though we insist that, relatively to 1882, these turls and bleats should be regarded as respectfully as we regard rag dolls that keep infants occupied and noiseless—it is the survival of rag dolls into maturity that we object to—so these pious and naïve ones who believed that 13,000 times something could have—that is, in quasi-existence—an exact and calculable resultant, whereas there is—in quasi-existence—nothing that can, except by delusion and convenience, be called a unit, in the first place—whose devotions to St. Isaac required blind belief in formulas of falling bodies—

Against data that were piling up, in their own time, of slow-falling meteorites; "milk warm" ones admitted even by Farrington and Merrill; at least one icy meteorite nowhere denied by the present orthodoxy, a datum as accessible to Thomson, in 1882, as it is now to us, because it was an occurrence of 1860. Beans and needles and tacks and a magnet. Needles and tacks adhere to and systematize relatively to a magnet, but, if some beans, too, be caught up, they are irreconcilables to this system and drop right out of it. A member of the Salvation Army may hear over and over data that seem so memorable to an evolutionist. It seems remarkable that they do not influence him—one finds that he cannot remember them. It is incredible that Sir William Thomson had never heard of slow-falling, cold meteorites. It is simply that he had no power to remember such irreconcilabilities.

And then Mr. Symons again. Mr. Symons was a man who probably did more for the science of meteorology than did any other man of his time: therefore he probably did more to hold back the science of meteorology than did any other man of his time. In Nature, 41-135, Mr. Symons says that Prof. Schwedoff's ideas are "very droll."

I think that even more amusing is our own acceptance that, not very far above this earth's surface, is a region that will be the subject of a whole new science—super-geography—with which we shall immortalize ourselves in the resentments of the schoolboys of the future—

Pebbles and fragments of meteors and things from Mars and Jupiter and Azuria: wedges, delayed messages, cannon balls, bricks, nails, coal and coke and charcoal and offensive old cargoes—things that coat in ice in some regions and things that get into areas so warm that they putrefy—or that there are all the climates of geography in super-geography. I shall have to accept that, floating in the sky of this earth, there often are fields of ice as extensive as those on the Arctic Ocean—volumes of water in which are many fishes and frogs—tracts of land covered with caterpillars—

Aviators of the future. They fly up and up. Then they get out and walk. The fishing's good: the bait's right there. They find messages from other worlds—and within three weeks there's a big trade worked up in forged messages. Sometime I shall write a guide book to the Super-Sargasso Sea, for aviators, but just at present there wouldn't be much call for it.

We now have more of our expression upon hail as a concomitant, or more data of things that have fallen from the sky, with hail.

In general, the expression is:

These things may have been raised from some other part of the earth's surface, in whirlwinds, or may not have fallen, and may have been upon the ground, in the first place—but were the hailstones found with them, raised from some other part of the earth's surface, or were the hailstones upon the ground, in the first place?

As I said before, this expression is meaningless as to a few instances; it is reasonable to think of some coincidence between the fall of hail and the fall of other things: but, inasmuch as there have been a good many instances,—we begin to suspect that this is not so much a book we're writing as a sanitarium for overworked coincidences. If not conceivably could very large hailstones and lumps of ice form in this earth's atmosphere, and so then had to come from external regions, then other things in or accompanying very large hailstones and lumps of ice came from external regions—which worries us a little: we may be instantly translated to the Positive Absolute.

Cosmos, 13-120, quotes a Virginia newspaper, that fishes said to have been catfishes, a foot long, some of them, had fallen, in 1853, at Norfolk, Virginia, with hail.

Vegetable débris, not only nuclear, but frozen upon the surfaces of large hailstones, at Toulouse, France, July 28, 1874. (La Science Pour Tous, 1874-270.)

Description of a storm, at Pontiac, Canada, July 11, 1864, in which it is said that it was not hailstones that fell, but "pieces of ice, from half an inch to over two inches in diameter" (Canadian Naturalist, 2-1-308):

"But the most extraordinary thing is that a respectable farmer, of undoubted veracity, says he picked up a piece of hail, or ice, in the center of which was a small green frog."

Storm at Dubuque, Iowa, June 16, 1882, in which fell hailstones and pieces of ice (Monthly Weather Review, June, 1882):

"The foreman of the Novelty Iron Works, of this city, states that in two large hailstones melted by him were found small living frogs." But the pieces of ice that fell upon this occasion had a peculiarity that indicates—though by as bizarre an indication as any we've had yet—that they had been for a long time motionless or floating somewhere. We'll take that up soon.

Living Age, 52-186:

That, June 30, 1841, fishes, one of which was ten inches long, fell at Boston; that, eight days later, fishes and ice fell at Derby.

In Timb's Year Book, 1842-275, it is said that, at Derby, the fishes had fallen in enormous numbers; from half an inch to two inches long, and some considerably larger. In the Athenæum, 1841-542, copied from the Sheffield Patriot, it is said that one of the fishes weighed three ounces. In several accounts, it is said that, with the fishes, fell many small frogs and "pieces of half-melted ice." We are told that the frogs and the fishes had been raised from some other part of the earth's surface, in a whirlwind; no whirlwind specified; nothing said as to what part of the earth's surface comes ice, in the month of July—interests us that the ice is described as "half-melted." In the London Times, July 15, 1841, it is said that the fishes were sticklebacks; that they had fallen with ice and small frogs, many of which had survived the fall. We note that, at Dunfermline, three months later (Oct. 7, 1841) fell many fishes, several inches in length, in a thunderstorm. (London Times, Oct. 12, 1841.)

Hailstones, we don't care so much about. The matter of stratification seems significant, but we think more of the fall of lumps of ice from the sky, as possible data of the Super-Sargasso Sea:

Lumps of ice, a foot in circumference, Derbyshire, England, May 12, 1811 (Annual Register, 1811-54); cuboidal mass, six inches in diameter, that fell at Birmingham, 26 days later (Thomson, Intro. to Meteorology, p. 179); size of pumpkins, Bangalore, India, May 22, 1851 (Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1855-35); masses of ice of a pound and a half each, New Hampshire, Aug. 13, 1851 (Lummis, Meteorology, p. 129); masses of ice, size of a man's head, in the Delphos tornado (Ferrel, Popular Treatise, p. 428); large as a man's hand, killing thousands of sheep, Texas, May 3, 1877 (Monthly Weather Review, May, 1877); "pieces of ice so large that they could not be grasped

Comments (0)