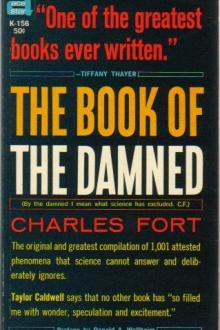

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

Very conspicuous and brilliant spots seen on the disk of Mars, October and November, 1911. (Popular Astronomy, Vol. 19, No. 10.)

So one of them accepted six or seven observations that were in agreement, except that they could not be regularized, upon a world—planet—satellite—and he gave it a name. He named it "Neith."

Monstrator and Elvera and Azuria and Super-Romanimus—

Or heresy and orthodoxy and the oneness of all quasiness, and our ways and means and methods are the very same. Or, if we name things that may not be, we are not of lonely guilt in the nomenclature of absences—

But now Leverrier and "Vulcan."

Leverrier again.

Or to demonstrate the collapsibility of a froth, stick a pin in the largest bubble of it. Astronomy and inflation: and by inflation we mean expansion of the attenuated. Or that the science of Astronomy is a phantom-film distended with myth-stuff—but always our acceptance that it approximates higher to substantiality than did the system that preceded it.

So Leverrier and the "planet Vulcan."

And we repeat, and it will do us small good to repeat. If you be of the masses that the astronomers have hypnotized—being themselves hypnotized, or they could not hypnotize others—or that the hypnotist's control is not the masterful power that it is popularly supposed to be, but only transference of state from one hypnotic to another—

If you be of the masses that the astronomers have hypnotized, you will not be able even to remember. Ten pages from here, and Leverrier and the "planet Vulcan" will have fallen from your mind, like beans from a magnet, or like data of cold meteorites from the mind of a Thomson.

Leverrier and the "planet Vulcan."

And much the good it will do us to repeat.

But at least temporarily we shall have an impression of a historic fiasco, such as, in our acceptance, could occur only in a quasi-existence.

In 1859, Dr. Lescarbault, an amateur astronomer, of Orgères, France, announced that, upon March 26, of that year, he had seen a body of planetary size cross the sun. We are in a subject that is now as unholy to the present system as ever were its own subjects to the system that preceded it, or as ever were slanders against miracles to the preceding system. Nevertheless few text-books go so far as quite to disregard this tragedy. The method of the systematists is slightingly to give a few instances of the unholy, and dispose of the few. If it were desirable to them to deny that there are mountains upon this earth, they would record a few observations upon some slight eminences near Orange, N.J., but say that commuters, though estimable persons in several ways, are likely to have their observations mixed. The text-books casually mention a few of the "supposed" observations upon "Vulcan," and then pass on.

Dr. Lescarbault wrote to Leverrier, who hastened to Orgères—

Because this announcement assimilated with his own calculations upon a planet between Mercury and the sun—

Because this solar system itself has never attained positiveness in the aspect of Regularity: there are to Mercury, as there are to Neptune, phenomena irreconcilable with the formulas, or motions that betray influence by something else.

We are told that Leverrier "satisfied himself as to the substantial accuracy of the reported observation." The story of this investigation is told in Monthly Notices, 20-98. It seems too bad to threaten the naïve little thing with our rude sophistications, but it is amusingly of the ingenuousness of the age from which present dogmas have survived. Lescarbault wrote to Leverrier. Leverrier hastened to Orgères. But he was careful not to tell Lescarbault who he was. Went right in and "subjected Dr. Lescarbault to a very severe cross-examination"—just the way you or I may feel at liberty to go into anybody's home and be severe with people—"pressing him hard step by step"—just as anyone might go into someone else's house and press him hard, though unknown to the hard-pressed one. Not until he was satisfied, did Leverrier reveal his identity. I suppose Dr. Lescarbault expressed astonishment. I think there's something utopian about this: it's so unlike the stand-offishness of New York life.

Leverrier gave the name "Vulcan" to the object that Dr. Lescarbault had reported.

By the same means by which he is, even to this day, supposed—by the faithful—to have discovered Neptune, he had already announced the probable existence of an Intra-Mercurial body, or group of bodies. He had five observations besides Lescarbault's upon something that had been seen to cross the sun. In accordance with the mathematical hypnoses of his era, he studied these six transits. Out of them he computed elements giving "Vulcan" a period of about 20 days, or a formula for heliocentric longitude at any time.

But he placed the time of best observation away up in 1877.

But even so, or considering that he still had probably a good many years to live, it may strike one that he was a little rash—that is if one has not gone very deep into the study of hypnoses—that, having "discovered" Neptune by a method which, in our acceptance, had no more to recommend it than had once equally well-thought-of methods of witch-finding, he should not have taken such chances: that if he was right as to Neptune, but should be wrong as to "Vulcan," his average would be away below that of most fortune-tellers, who could scarcely hope to do business upon a fifty per cent. basis—all that the reasoning of a tyro in hypnoses.

The date:

March 22, 1877.

The scientific world was up on its hind legs nosing the sky. The thing had been done so authoritatively. Never a pope had said a thing with more of the seeming of finality. If six observations correlated, what more could be asked? The Editor of Nature, a week before the predicted event, though cautious, said that it is difficult to explain how six observers, unknown to one another, could have data that could be formulated, if they were not related phenomena.

In a way, at this point occurs the crisis of our whole book.

Formulas are against us.

But can astronomic formulas, backed up by observations in agreement, taken many years apart, calculated by a Leverrier, be as meaningless, in a positive sense, as all other quasi-things that we have encountered so far?

The preparations they made, before March 22, 1877. In England, the Astronomer Royal made it the expectation of his life: notified observers at Madras, Melbourne, Sydney, and New Zealand, and arranged with observers in Chili and the United States. M. Struve had prepared for observations in Siberia and Japan—

March 22, 1877—

Not absolutely, hypocritically, I think it's pathetic, myself. If anyone should doubt the sincerity of Leverrier, in this matter, we note, whether it has meaning or not, that a few months later he died.

I think we'll take up Monstrator, though there's so much to this subject that we'll have to come back.

According to the Annual Register, 9-120, upon the 9th of August, 1762, M. de Rostan, of Basle, France, was taking altitudes of the sun, at Lausanne. He saw a vast, spindle-shaped body, about three of the sun's digits in breadth and nine in length, advancing slowly across the disk of the sun, or "at no more than half the velocity with which the ordinary solar spots move." It did not disappear until the 7th of September, when it reached the sun's limb. Because of the spindle-like form, I incline to think of a super-Zeppelin, but another observation, which seems to indicate that it was a world, is that, though it was opaque, and "eclipsed the sun," it had around it a kind of nebulosity—or atmosphere? A penumbra would ordinarily be a datum of a sun spot, but there are observations that indicate that this object was at a considerable distance from the sun:

It is recorded that another observer, at Paris, watching the sun, at this time, had not seen this object:

But that M. Croste, at Sole, about forty-five German leagues northward from Lausanne, had seen it, describing the same spindle-form, but disagreeing a little as to breadth. Then comes the important point: that he and M. de Rostan did not see it upon the same part of the sun. This, then, is parallax, and, compounded with invisibility at Paris, is great parallax—or that, in the course of a month, in the summer of 1762, a large, opaque, spindle-shaped body traversed the disk of the sun, but at a great distance from the sun. The writer in the Register says: "In a word, we know of nothing to have recourse to, in the heavens, by which to explain this phenomenon." I suppose he was not a hopeless addict to explaining. Extraordinary—we fear he must have been a man of loose habits in some other respects.

As to us—

Monstrator.

In the Monthly Notices of the R.A.S., February, 1877, Leverrier, who never lost faith, up to the last day, gives the six observations upon an unknown body of planetary size, that he had formulated:

Fritsche, Oct. 10, 1802; Stark, Oct. 9, 1819; De Cuppis, Oct. 30, 1839; Sidebotham, Nov. 12, 1849; Lescarbault, March 26, 1859; Lummis, March 20, 1862.

If we weren't so accustomed to Science in its essential aspect of Disregard, we'd be mystified and impressed, like the Editor of Nature, with the formulation of these data: agreement of so many instances would seem incredible as a coincidence: but our acceptance is that, with just enough disregard, astronomers and fortune-tellers can formulate anything—or we'd engage, ourselves, to formulate periodicities in the crowds in Broadway—say that every Wednesday morning, a tall man, with one leg and a black eye, carrying a rubber plant, passes the Singer Building, at quarter past ten o'clock. Of course it couldn't really be done, unless such a man did have such periodicity, but if some Wednesday mornings it should be a small child lugging a barrel, or a fat negress with a week's wash, by ordinary disregard that would be prediction good enough for the kind of quasi-existence we're in.

So whether we accuse, or whether we think that the word "accuse" over-dignifies an attitude toward a quasi-astronomer, or mere figment in a super-dream, our acceptance is that Leverrier never did formulate observations—

That he picked out observations that could be formulated—

That of this type are all formulas—

That, if Leverrier had not been himself helplessly hypnotized, or if he had had in him more than a tincture of realness, never could he have been beguiled by such a quasi-process: but that he was hypnotized, and so extended, or transferred, his condition to others, that upon March 22, 1877, he had this earth bristling with telescopes, with the rigid and almost inanimate forms of astronomers behind them—

And not a blessed thing of any unusuality was seen upon that day or succeeding days.

But that the science of Astronomy suffered the slightest in prestige?

It couldn't. The spirit of 1877 was behind it. If, in an embryo, some cells should not live up to the phenomena of their era, the others will sustain the scheduled appearances. Not until an embryo enters the mammalian stage are cells of the reptilian stage false cells.

It is our acceptance that there were many equally authentic reports upon large planetary bodies that had been seen near the sun; that, of many, Leverrier picked out six; not then deciding that all the other observations related to still other large, planetary bodies, but arbitrarily, or hypnotically, disregarding—or heroically disregarding—every one of them—that to formulate at all he had to exclude falsely. The dénouement killed him, I think. I'm not at all inclined to place him with the Grays and Hitchcocks and Symonses. I'm not, because, though it was rather unsportsmanlike to put the date so far ahead, he did give a date, and he did stick to it with such a high approximation—

I think Leverrier was translated to

Comments (0)