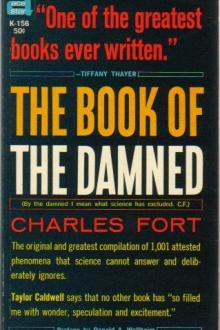

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

The disregarded:

Observation, of July 26, 1819, by Gruthinson—but that was of two bodies that crossed the sun together—

Nature, 14-469:

That, according to the astronomer, J.R. Hind, Benjamin Scott, City Chamberlain of London, and Mr. Wray, had, in 1847, seen a body similar to "Vulcan" cross the sun.

Similar observation by Hind and Lowe, March 12, 1849 (L'Année Scientifique, 1876-9).

Nature, 14-505:

Body of apparent size of Mercury, seen, Jan. 29, 1860, by F.A.R. Russell and four other observers, crossing the sun.

De Vico's observation of July 12, 1837 (Observatory, 2-424).

L'Année Scientifique, 1865-16:

That another amateur astronomer, M. Coumbray, of Constantinople, had written to Leverrier, that, upon the 8th of March, 1865, he had seen a black point, sharply outlined, traverse the disk of the sun. It detached itself from a group of sun spots near the limb of the sun, and took 48 minutes to reach the other limb. Figuring upon the diagram sent by M. Coumbray, a central passage would have taken a little more than an hour. This observation was disregarded by Leverrier, because his formula required about four times that velocity. The point here is that these other observations are as authentic as those that Leverrier included; that, then, upon data as good as the data of "Vulcan," there must be other "Vulcans"—the heroic and defiant disregard, then, of trying to formulate one, omitting the others, which, by orthodox doctrine, must have influenced it greatly, if all were in the relatively narrow space between Mercury and the sun.

Observation upon another such body, of April 4, 1876, by M. Weber, of Berlin. As to this observation, Leverrier was informed by Wolf, in August, 1876 (L'Année Scientifique, 1876-7). It made no difference, so far as can be known, to this notable positivist.

Two other observations noted by Hind and Denning—London Times, Nov. 3, 1871, and March 26, 1873.

Monthly Notices of the R.A.S., 20-100:

Standacher, February, 1762; Lichtenberg, Nov. 19, 1762; Hoffman, May, 1764; Dangos, Jan. 18, 1798; Stark, Feb. 12, 1820. An observation by Schmidt, Oct. 11, 1847, is said to be doubtful: but, upon page 192, it is said that this doubt had arisen because of a mistaken translation, and two other observations by Schmidt are given: Oct. 14, 1849, and Feb. 18, 1850—also an observation by Lofft, Jan. 6, 1818. Observation by Steinheibel, at Vienna, April 27, 1820 (Monthly Notices, 1862).

Haase had collected reports of twenty observations like Lescarbault's. The list was published in 1872, by Wolf. Also there are other instances like Gruthinsen's:

Amer. Jour. Sci., 2-28-446:

Report by Pastorff that he had seen twice in 1836, and once in 1837, two round spots of unequal size moving across the sun, changing position relatively to each other, and taking a different course, if not orbit, each time: that, in 1834, he had seen similar bodies pass six times across the disk of the sun, looking very much like Mercury in his transits.

March 22, 1876—

But to point out Leverrier's poverty-stricken average—or discovering planets upon a fifty per cent. basis—would be to point out the low percentage of realness in the quasi-myth-stuff of which the whole system is composed. We do not accuse the text-books of omitting this fiasco, but we do note that theirs is the conventional adaptation here of all beguilers who are in difficulties—

The diverting of attention.

It wouldn't be possible in a real existence, with real mentality, to deal with, but I suppose it's good enough for the quasi-intellects that stupefy themselves with text-books. The trick here is to gloss over Leverrier's mistake, and blame Lescarbault—he was only an amateur—had delusions. The reader's attention is led against Lescarbault by a report from M. Lias, director of the Brazilian Coast Survey, who, at the time of Lescarbault's "supposed" observation had been watching the sun in Brazil, and, instead of seeing even ordinary sun spots, had noted that the region of the "supposed transit" was of "uniform intensity."

But the meaninglessness of all utterances in quasi-existence—

"Uniform intensity" turns our way as much as against us—or some day some brain will conceive a way of beating Newton's third law—if every reaction, or resistance, is, or can be, interpretable as stimulus instead of resistance—if this could be done in mechanics, there's a way open here for someone to own the world—specifically in this matter, "uniform intensity" means that Lescarbault saw no ordinary sun spot, just as much as it means that no spot at all was seen upon the sun. Continuing the interpretation of a resistance as an assistance, which can always be done with mental forces—making us wonder what applications could be made with steam and electric forces—we point out that invisibility in Brazil means parallax quite as truly as it means absence, and, inasmuch as "Vulcan" was supposed to be distant from the sun, we interpret denial as corroboration—method of course of every scientist, politician, theologian, high-school debater.

So the text-books, with no especial cleverness, because no especial cleverness is needed, lead the reader into contempt for the amateur of Orgères, and forgetfulness of Leverrier—and some other subject is taken up.

But our own acceptance:

That these data are as good as ever they were;

That, if someone of eminence should predict an earthquake, and if there should be no earthquake at the predicted time, that would discredit the prophet, but data of past earthquakes would remain as good as ever they had been. It is easy enough to smile at the illusion of a single amateur—

The mass-formation:

Fritsche, Stark, De Cuppis, Sidebotham, Lescarbault, Lummis, Gruthinson, De Vico, Scott, Wray, Russell, Hind, Lowe, Coumbray, Weber, Standacher, Lichtenberg, Dangos, Hoffman, Schmidt, Lofft, Steinheibel, Pastorff—

These are only the observations conventionally listed relatively to an Intra-Mercurial planet. They are formidable enough to prevent our being diverted, as if it were all the dream of a lonely amateur—but they're a mere advance-guard. From now on other data of large celestial bodies, some dark and some reflecting light, will pass and pass and keep on passing—

So that some of us will remember a thing or two, after the procession's over—possibly.

Taking up only one of the listed observations—

Or our impression that the discrediting of Leverrier has nothing to do with the acceptability of these data:

In the London Times, Jan. 10, 1860, is Benjamin Scott's account of his observation:

That, in the summer of 1847, he had seen a body that had seemed to be the size of Venus, crossing the sun. He says that, hardly believing the evidence of his sense of sight, he had looked for someone, whose hopes or ambitions would not make him so subject to illusion. He had told his little son, aged five years, to look through the telescope. The child had exclaimed that he had seen "a little balloon" crossing the sun. Scott says that he had not had sufficient self-reliance to make public announcement of his remarkable observation at the time, but that, in the evening of the same day, he had told Dr. Dick, F.R.A.S., who had cited other instances. In the Times, Jan. 12, 1860, is published a letter from Richard Abbott, F.R.A.S.: that he remembered Mr. Scott's letter to him upon this observation, at the time of the occurrence.

I suppose that, at the beginning of this chapter, one had the notion that, by hard scratching through musty old records we might rake up vague, more than doubtful data, distortable into what's called evidence of unrecognized worlds or constructions of planetary size—

But the high authenticity and the support and the modernity of these of the accursed that we are now considering—

And our acceptance that ours is a quasi-existence, in which above all other things, hopes, ambitions, emotions, motivations, stands Attempt to Positivize: that we are here considering an attempt to systematize that is sheer fanaticism in its disregard of the unsystematizable—that it represented the highest good in the 19th century—that it is mono-mania, but heroic mono-mania that was quasi-divine in the 19th century—

But that this isn't the 19th century.

As a doubly sponsored Brahmin—in the regard of Baptists—the objects of July 29, 1878, stand out and proclaim themselves so that nothing but disregard of the intensity of mono-mania can account for their reception by the system:

Or the total eclipse of July 29, 1878, and the reports by Prof. Watson, from Rawlins, Wyoming, and by Prof. Swift, from Denver, Colorado: that they had seen two shining objects at a considerable distance from the sun.

It's quite in accord with our general expression: not that there is an Intra-Mercurial planet, but that there are different bodies, many vast things; near this earth sometimes, near the sun sometimes; orbitless worlds, which, because of scarcely any data of collisions, we think of as under navigable control—or dirigible super-constructions.

Prof. Watson and Prof. Swift published their observations.

Then the disregard that we cannot think of in terms of ordinary, sane exclusions.

The text-book systematists begin by telling us that the trouble with these observations is that they disagree widely: there is considerable respectfulness, especially for Prof. Swift, but we are told that by coincidence these two astronomers, hundreds of miles apart, were illuded: their observations were so different—

Prof. Swift (Nature, Sept. 19, 1878):

That his own observation was "in close approximation to that given by Prof. Watson."

In the Observatory, 2-161, Swift says that his observations and Watson's were "confirmatory of each other."

The faithful try again:

That Watson and Swift mistook stars for other bodies.

In the Observatory, 2-193, Prof. Watson says that he had previously committed to memory all stars near the sun, down to the seventh magnitude—

And he's damned anyway.

How such exclusions work out is shown by Lockyer (Nature, Aug. 20, 1878). He says: "There is little doubt that an Intra-Mercurial planet has been discovered by Prof. Watson."

That was before excommunication was pronounced.

He says:

"If it will fit one of Leverrier's orbits"—

It didn't fit.

In Nature, 21-301, Prof. Swift says:

"I have never made a more valid observation, nor one more free from doubt."

He's damned anyway.

We shall have some data that will not live up to most rigorous requirements, but, if anyone would like to read how carefully and minutely these two sets of observations were made, see Prof. Swift's detailed description in the Am. Jour. Sci., 116-313; and the technicalities of Prof. Watson's observations in Monthly Notices, 38-525.

Our own acceptance upon dirigible worlds, which is assuredly enough, more nearly real than attempted concepts of large planets relatively near this earth, moving in orbits, but visible only occasionally; which more nearly approximates to reasonableness than does wholesale slaughter of Swift and Watson and Fritsche and Stark and De Cuppis—but our own acceptance is so painful to so many minds that, in another of the charitable moments that we have now and then for the sake of contrast, we offer relief:

The things seen high in the sky by Swift and Watson—

Well, only two months before—the horse and the barn—

We go on with more observations by astronomers, recognizing that it is the very thing that has given them life, sustained them, held them together, that has crushed all but the quasi-gleam of independent life out of them. Were they not systematized, they could not be at all, except sporadically and without sustenance. They are systematized: they must not vary from the conditions of the system: they must not break away for themselves.

The two great commandments:

Thou shalt not break Continuity;

Thou shalt try.

We go on with these disregarded data, some of which, many of which, are of the highest degree of acceptability. It is the System that pulls back its variations, as this earth is pulling back the Matterhorn. It is the System that nourishes and rewards, and also freezes out life with the chill of disregard. We do note that, before excommunication is pronounced, orthodox journals do liberally enough record unassimilable observations.

All things merge away into everything else.

That is Continuity.

So the System merges away and evades us when we try to focus against it.

We have complained a great deal. At least we are not so dull as to have the delusion that we know just exactly what it is that we are complaining about. We speak seemingly definitely enough of "the System," but we're building upon observations

Comments (0)